|

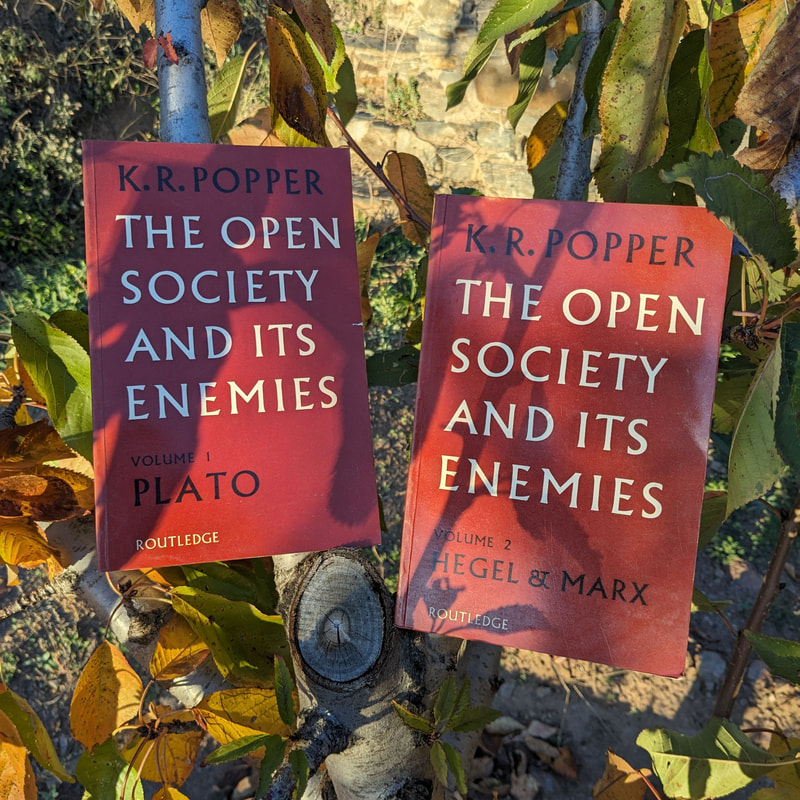

This work represented for me an investigation of where I stood in terms of political philosophy. I knew what I felt alright, but I lacked the articulation of it.

Freedom-loving dreamer that I was, Popper’s democratic thesis deeply impressed me with its championing of the rights of the individual over any notion of an ideal society. The absolutist who is hellbent on achieving the perfect state, allegedly “for the good of all,” is only too ready to sacrifice and tyrannize those who stand in its way. These are clearly not legitimate citizens and “all” does not include them. Were it ever attainable, the so-called ideal society would then have to be preserved at all costs, ruled with an iron fist, lest dissenters threaten it. Sound familiar? Popper sets out a sound scientific method for the development of theoretical models, namely, that a valuable hypothesis is one that is rich in substance and—crucially—testable and falsifiable. It is perfectly fair for Popper to go on to apply this methodology to the social sciences, but his distrust of the faculty of intuition is such that it has no place at all in his epistemology. He omits to recognize that intuition or imagination typically propose the creative ideas and models that enrich the social dynamic. There is no reason why these may not then be subjected to his rigorous testing to see what the observable results are. For this to happen, there must first be seriousness, honesty and humility in the investigator. This condition of the psyche is the horse which will draw Popper’s cart. When the political philosopher says that the psyche lies outside the scope of their inquiry, one is tempted to ask: why? If the whole edifice of your reasoning can be invalidated by the absence of the psychological drive to put it into practice, don’t you want to turn your attention to that?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed