|

I loved the surprises and the symbols. The lilting music. The audacious proposition and the firm pace. The exploratory purposiveness. If most of the classical allusions were lost on me (I still find quite a lot of Eliot just too clever), I could still appreciate the collapsing of time, joining ancient figures to the modern in constellations of grimy London, Margate juxtaposed with Carthage like tragedy in a music hall, images grabbed from all over the world mind.

The lyricism that best spoke to and for me was rooted in the city. Windows and horses, beer and fog, Eliot finding weird beauty while seeking with his pen to pin down answers from the spirit worlds of his intellect, from windswept cultural landscapes of forlorn life, in words. I can still get taken up by these bold, clean, stylish poems that sit restless on the page, waiting and wanting to be read out loud and sing. Let me put this in your mind: read The Hollow Men and imagine it being declaimed by Jim Morrison in that fierce, passionate delivery of his. It sure as hell works for me.

0 Comments

On travels through South America in the 1980s, I was given this book and found myself transported by the intimate clarity of its directness to Rome and the first century AD and, more than that, to the timelessness of wisdom. This rare intelligence is, of course, Yourcenar’s, who effaces herself from the imagined memoir and leaves the stage to Hadrian.

His personal, political and military account is no confession: he is Emperor and recognizes no earthly judge above him. It means that he has no mind to be anything but candid and honest, and to take time and care in crafting the missive to his successor with the elegance that belongs to truth. Hadrian is unafraid to wield great power and deal death, but he is no Caligula and takes no perverse delight in it. He is a pragmatist, dealing with the over-extended Empire as best he knows. At all events, the author does not seek to judge, but to understand and portray. Yourcenar writes beautifully. She succeeds in evoking and making her own the refined, assured prose of the ancient classics without ever being donnish. Only Robert Graves comes close in this. There is a great absence of pride in Hadrian and of ego in his fictional amanuensis. Memoirs of Hadrian is simply one of the most accomplished books I have ever come across. This work represented for me an investigation of where I stood in terms of political philosophy. I knew what I felt alright, but I lacked the articulation of it.

Freedom-loving dreamer that I was, Popper’s democratic thesis deeply impressed me with its championing of the rights of the individual over any notion of an ideal society. The absolutist who is hellbent on achieving the perfect state, allegedly “for the good of all,” is only too ready to sacrifice and tyrannize those who stand in its way. These are clearly not legitimate citizens and “all” does not include them. Were it ever attainable, the so-called ideal society would then have to be preserved at all costs, ruled with an iron fist, lest dissenters threaten it. Sound familiar? Popper sets out a sound scientific method for the development of theoretical models, namely, that a valuable hypothesis is one that is rich in substance and—crucially—testable and falsifiable. It is perfectly fair for Popper to go on to apply this methodology to the social sciences, but his distrust of the faculty of intuition is such that it has no place at all in his epistemology. He omits to recognize that intuition or imagination typically propose the creative ideas and models that enrich the social dynamic. There is no reason why these may not then be subjected to his rigorous testing to see what the observable results are. For this to happen, there must first be seriousness, honesty and humility in the investigator. This condition of the psyche is the horse which will draw Popper’s cart. When the political philosopher says that the psyche lies outside the scope of their inquiry, one is tempted to ask: why? If the whole edifice of your reasoning can be invalidated by the absence of the psychological drive to put it into practice, don’t you want to turn your attention to that? For a long while I gravitated towards tales of the outsider type and Jonathan Whalen is another one, estranged from meaningful experience by character and privilege.

If Camus’s Meursault was an outsider in spite of himself—with no real sense of self, in fact—Kosiński’s Whalen is a self-indulgent one. What they share is a searing honesty, without the least desire to defend their actions or make a favourable impression. When money and opium and sex are too easily come by, and even murder is an available commodity, Whalen’s hedonistic degeneration demonstrates the emptiness of the materialistic values that he, too, has bought into. The anti-hero’s freedom from a moral code or sense of obligation can offer a vicarious thrill to the spectator, when they are hard put to find much that is worthwhile or attractive in the society whose rules are being broken. But we do not care about Whalen. He is no rebel and has no cause. The sparse observational style and diary-like entries describe a blithe, fragmented existence lived in disconnected pieces. Whalen’s fate is not to develop. Like the Devil Tree, he has no roots, and there will be no redemption. The romance of the subject matter got me and so did Hemingway’s inimitable style.

The first book set in Spain that I ever read, it sowed seeds that are now tall trees. During a phase of reading Eastern European émigrés, when Communist Bloc still existed, I came across this sprawling, thoughtful and entertaining novel.

Swinging between Danny’s former life in Czechoslovakia and a new one in Canada, it covers Skvorecky’s own wide-ranging preoccupations and experiences of very different societies and political regimes. There aren’t so many books with such a provenance and it documents that certain time and place and mood. I was working on the grape harvest in Germany one time, when I asked a friend why the Kurdish women picking in the next row were singing. “They’re not singing,” he said. “They’re talking.” It was musical speech, very pretty, of which I understood not a thing.

When it came to art, I was just as clueless. “Very accomplished. Interesting. Impressive.” In other words: I didn’t understand a blind word of its language. Opening this book was like being handed an interpretive key. In their work, Gombrich explained, the artist is problem-solving. Look at a well-known painting: there was something that the artist was trying to work out, communicate or suggest, and it was only in this way that they could do it. It might mean following the representational idiom of their day and culture, or it might mean making a radical break from it and doing something quite different. To shift from two-dimensional images to three was a cognitive leap of the first order. When humanist traits influenced religious imagery in the Renaissance and secular figures were portrayed, it indicated times of social and philosophical change and a challenge to the hegemony of the Church. Cubism similarly arose in an era of radically shifting perspectives. Punk art just wanted to stick two fingers up at the establishment. If you know its symbolic language, the painting will tell you its story. A connection in understanding can then be made, travelling between the verbal and the non-verbal, and meaning is in the psyche of the beholder. Unless an art work speaks directly to me in what Jung would call “archetypal statements” having “nothing to do with reason,” I need to have an idea of its context and the mind and intent of the artist. Otherwise, I might as well go straight to the museum café. And you have seen the price of those muffins? Few people did more to document and expose the staggering scale of Stalin’s crimes than Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. His diligence and skill in collating the material for this absorbing and prodigious record represent a singular literary-political accomplishment—all the more so when one bears in mind the oppressive and risky conditions under which he compiled notes and wrote. It is remarkable that the work ever saw the light of day. When he had no paper to write on in his prison cell, he would memorize the tragedies of fellow zeks so that they would not be buried under the rubble of history.

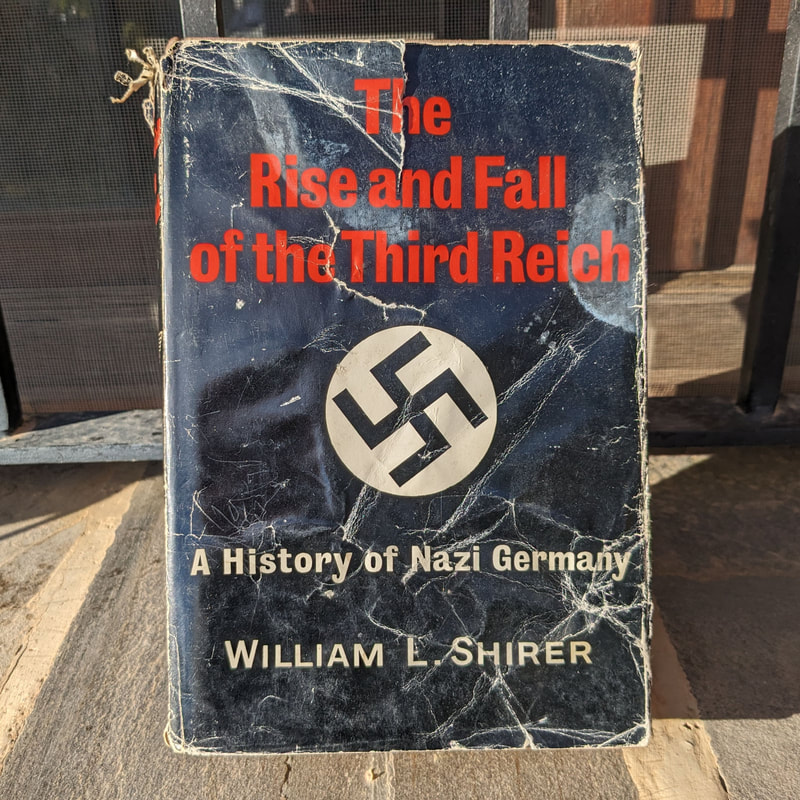

The Gulag Archipelago is monumental in its size, conscientiousness, commitment to individuals’ stories and humanity, and Solzhenitsyn’s own experiences as a political prisoner make him uniquely authoritative. It is one thing to know of the murders of millions as an accepted historical datum and quite another to learn facts in detail, the cruelties and the sufferings with names and places. Then the enormity of it all comes through. I read the three volumes with astonishment at the persecution of so many and admiration for this man who stood up to make it known in such an accessible way. He treats the reader like a fellow human being, not an audience to be educated. Solzhenitsyn was an author, not a professional historian. He brings the material alive by telling true stories and while he does so, the dead are given the respect of memory. When I grew up, the concept of evil had a physical embodiment in the figure of one man: Adolf Hitler. Even now, I find the sight of his face or the sound of his voice unnerving.

After reading Shirer’s book, which provided plenty of insights into Hitler’s character, Bullock’s biography went further in explaining the devastating success of this small-minded man. His very lack of complexity meant that he was not held back by considerations that might give others pause. The only virtues and obligations he recognized were strength of will and force. Duplicity and single-minded pitilessness were simply two more weapons in his armoury with which to subjugate and crush the weak. Allied to a simplistic ideology of Germany’s destiny, might is right and the Arian superman, his drive to attain political power was only ever heading in one direction: military aggression and wars of conquest, domestic tyranny and the elimination all who differed. Such hatred always needs a scapegoat, and the Jews were his terribly convenient and defenceless target. Ninety years later, in a Europe where Germany has long been a major guarantor of peace, justice and stability, we have another war of nationalistic ideology, with the people of Ukraine being murdered by another cold-blooded dictator. We cannot fail Ukraine, or allow despotism to prevail. Hitler and his Nazis stand as a warning to us for all time. It’s Armistice Day. A day for remembering, and heeding the lessons of wars past.

My parents and their generation, who lived and fought through the Second World War, wanted only to put that past behind them. This culture extended to schools, where we were not taught about the war and its history, even though Britain was a victor and the defeated regime vilified as an abomination that we might learn from. In the newest war, in the Middle East, thousands of children are being killed and the British Home Secretary would like to ban a march for peace, calling it a “hate march.” Who is the abomination now? Who will stay the hand of the twisted men with murderous ideologies? I didn’t read Shirer’s book until my mid-twenties, by which time I had studied German, made German friends, and the war was long confined to the past. Before I could begin to understand the how’s and why’s Hitler’s rise to power and the war, I needed a book that laid out what happened and when. This history does exactly that. My father was just 16 when he joined a Royal Navy ship at the beginning of WWII. He had an intense dislike for what he called “war bores” and never spoke about his experiences to us kids, although he opened up a bit in later years. He survived the war, but emotionally he never really recovered. If he were alive, today would be his 100th birthday, and I'm remembering. |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed