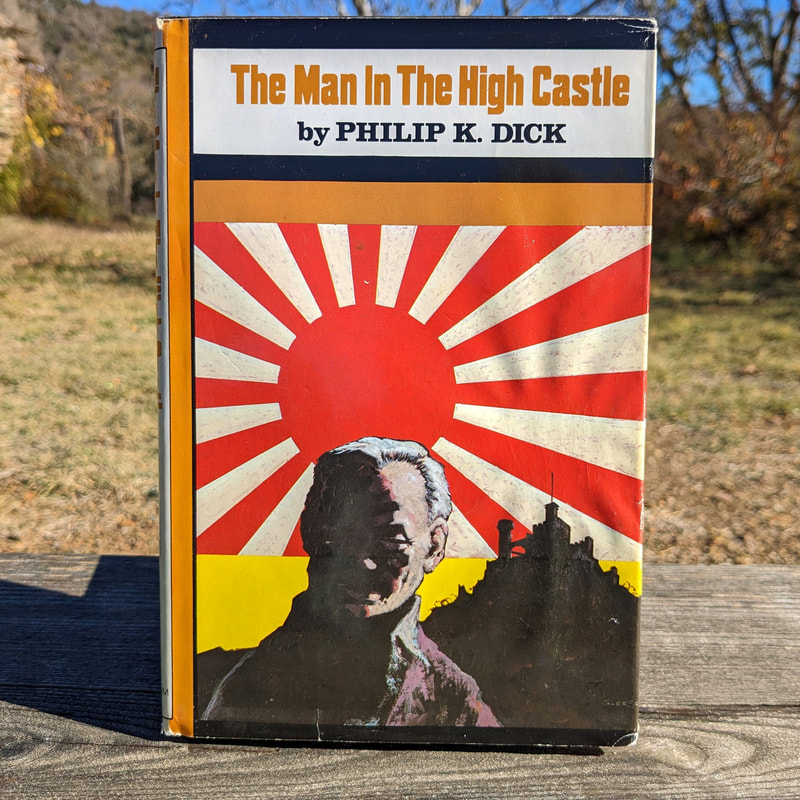

1962 First edition 1962 First edition One of Dick’s finest is a flawed favourite of mine.

Once, around the age of thirty, I discovered Philip K. Dick, I was blissfully fixated, reading one title after another, knowing that any book with his name to it would delight me, a sensation I hadn’t known since I was a kid and read The Famous Five or the Three Investigators, and wouldn’t again until I came across Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey & Maturin multi-book epic. Unlike these, Dick’s books weren’t a series. Instead, they were conjoined by one man’s voice and vision and common to them all was a pace and an intrigue carrying the story along, and an empathy for his protagonists which meant that that their fate was taken seriously no matter how outlandish their predicament. There was also a wave of humour that passed through the narratives like the sweep of a radar and caused them to sparkle and smile in places. This one was different. Dick’s characteristic weirdness and its accompanying comic element are absent, for he is considering an alternative fate of our world that would have been no laughing matter. After a cursory look at the blurb, I remember opening The Man in the High Castle hungrily at page one and starting to read. Here, as usual, we were in Dick’s 1950s/60s California––only it was unusual. There was something odd about the writing that I couldn’t put my finger on: and then it clicked. His American store owner was speaking and thinking with Japanese speech patterns and inflection. In this version of history, the Allies lost World War II, after which the western half of the USA was allotted to the Japanese and the eastern to Germany. The colonizers’ cultural mores have become established in the Pacific Sates of America and Mr Childan bows spontaneously to his high-ranking Japanese customers. The plot thickens nicely until the denouement, which I found inexplicably weak and disappointing. Later, I think I discovered why. Dick’s imagined history manages to be both entertaining and chillingly thought-provoking. Africa is referred to as a “Nazi experiment” which went too far even for them and does not bear speaking about in detail. A Rosenberg pamphlet regrets, “Unfortunately, however ––”: and leaves it there. “That huge empty ruin” is the stark image that we are given. History, of course, could well have gone the other way. In which case, my Royal Navy father wouldn’t have survived and I wouldn’t be here writing this. Had the Germans wiped out the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk and Britain sued for peace (as it very nearly did: Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, was all for it), Hitler’s war machine may have grown invincible. The eponymous Man in the High Castle, Hawthorne Abendsen, has written an alternative alternative history, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, in which the Axis powers lost. That it didn’t quite turn out the same way as our own history goes to the heart of what Dick is exploring in the novel: the idea of a multiverse in which parallel realities coexist, or of a fictional reality that we inhabit unknowingly. What makes Abendsen’s proposition fascinating is that it turns out to be true. What makes it fall so terribly flat is the way that the ending is handled. Hawthorne’s character (apathetic, “not sure of anything”) is insufferably feeble and so is the novel’s culmination. Dick’s boldness and deftness of touch desert him at the worst possible moment. The Chinese I Ching plays a mystical, oracular role in the narrative. Dick justifies its presence in Japanese culture by smuggling in an animist Shinto idea: “Spirit animates it”, but it’s ultimately out of place. It seems that Dick, like the fictional Abendsen, wrote his novel casting the I Ching to determine the outcome of events and this whim is, I suspect, is what let him down. If he had trusted his own nous rather than the oracle, I am sure that the ending would have been immeasurably stronger. As it is, faced with the reveal and its huge implication, Abendsen is blasé, heedless of danger, and the novel simply peters out.

0 Comments

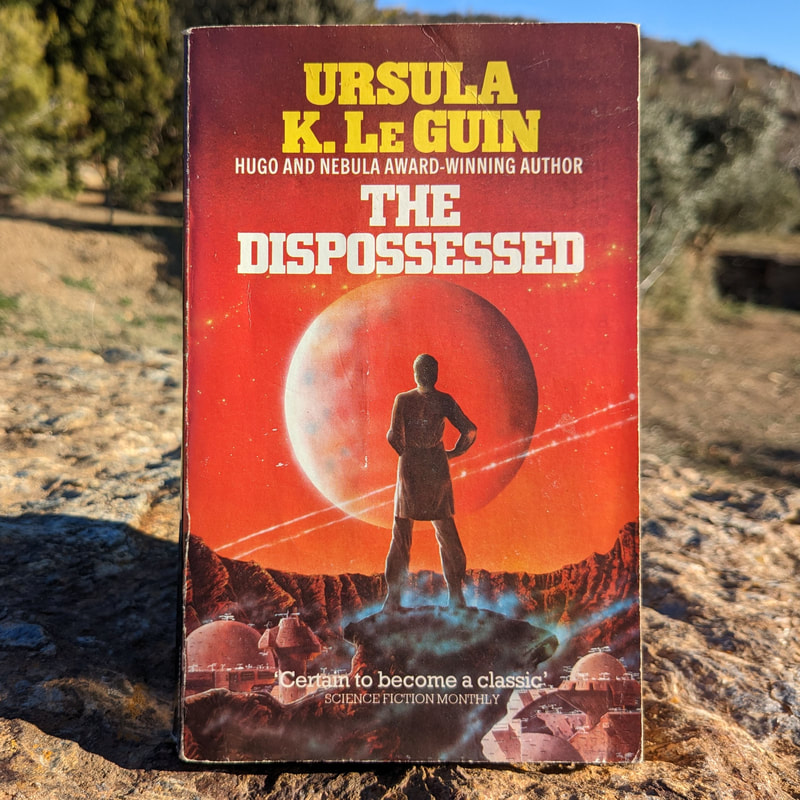

A physicist from an austere, industrious, anarchist society on a moon descends to the planet that the satellite orbits, where he is ushered into a world of private property, capitalist divisiveness, and sybaritic amorality. Finding himself cut off from the seriousness of purpose and boundaries that defined his world, Shevek seeks to refocus on his mission and his true being.

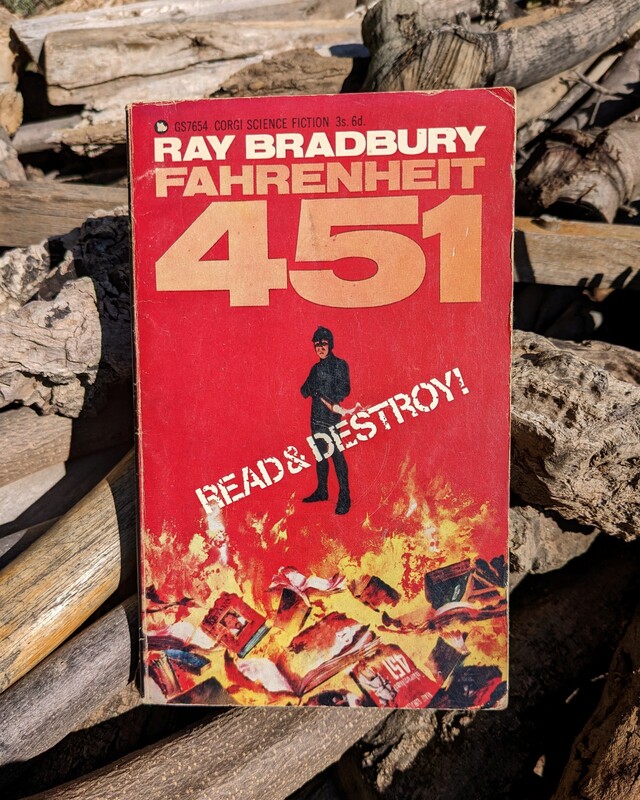

The questions and reflections on reality and ways of living that occupy Shevek are rooted in the very scientific discoveries that he is making about time and simultaneity. A born freethinker, he is unafraid to critique whatever he encounters. The contrasting social philosophies of Anarres and Urras, he notes, are reflected in the differing structures of language of the two worlds, which not only reinforce social prejudices but create or dispel error in perception. Me and mine contrast with the interactive collective and the all. Written in the spirit of the Tao te Ching––which she also translated– Ursula Le Guin’s masterful novel examines how true freedom can inform human experience. Her imperfect “ambiguous utopia” is the closest depiction of a workable anarchist society that I have ever read, although the story is anything but a political tract. At the heart of the story lie Shevek’s personal struggles and the difficulties interposed in his relationship with Takver, movingly and skillfully portrayed. It is ultimately fitting that Shevek meets representatives of the Hainish culture that Le Guin proposed in a number of her books. This interplanetary confederation is based upon a principle that is the only possible outcome for humanity if we are to survive in the long run: that of peaceful cooperation and the tolerance of differences. Like The Left Hand of Darkness, the depth, intelligence, compassion and hope of The Dispossessed spoke to my mind and my heart. It is one of the great books of my life. What Bradbury was standing up for here was the right to think differently. He was reacting to McCarthyism, but it could be almost any era.

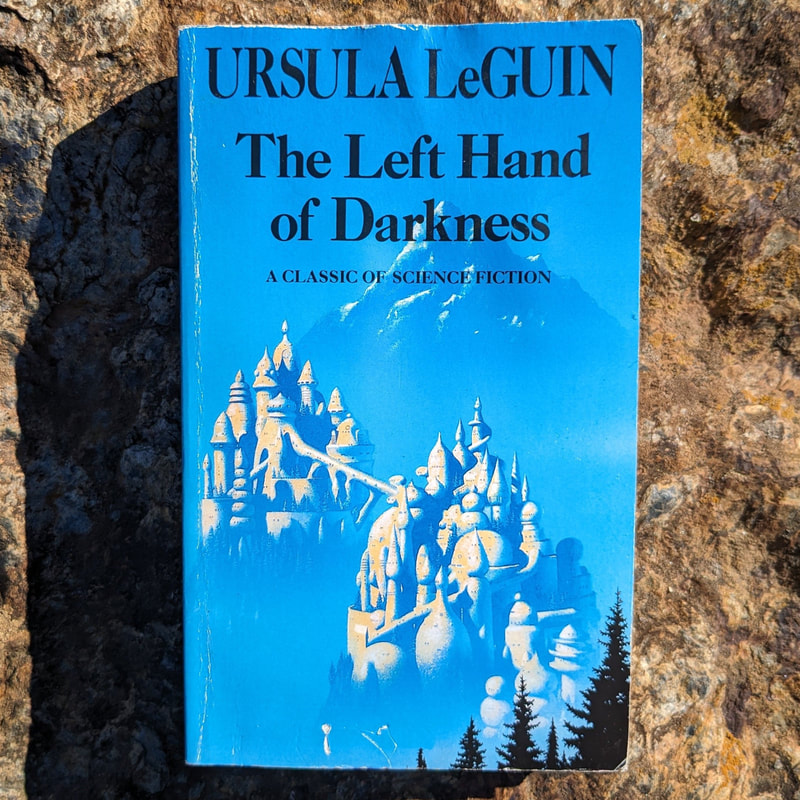

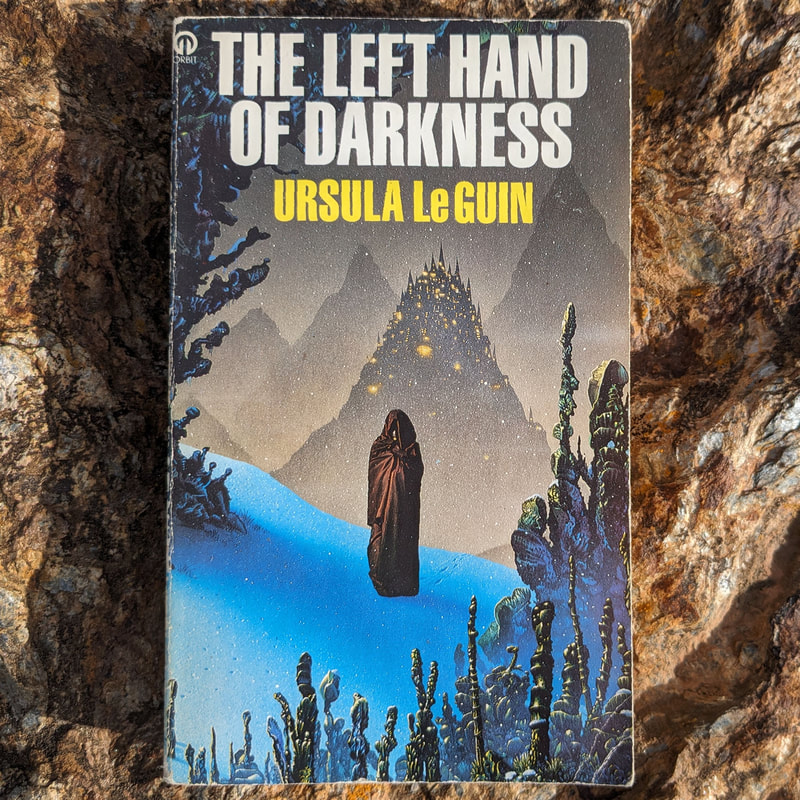

Seventy years on––he published this short novel in 1953––books are still being burned, banned, censored and butchered, and they always will be. Unless anyone really believes that we will eradicate fear and intolerance, there will always be books that so challenge some people’s worldview that they cannot allow them to exist. The Inquisition may no longer burn freethinkers, but authors can find themselves hounded, oppressed, physically attacked and thrown into jail. So it goes! Anyhow, this little book represents a trumpet call for the freedom to imagine, without which humanity is a lost cause. The image of the self-exiled drifters who memorize books––“I am Plato’s Republic”––is unforgettable.  I love this book with all my heart. I am not much of a one to reread books, but I know that I will always return to The Left Hand of Darkness because it has that certain strangeness that speaks of home.

Genly Ai treads with respect, gentle irony and some trepidation–because of real risk to his physical safety–among the Gethenians of the planet Winter. As a Hainish man, he struggles to deal with the permanent icy cold and the volatile ambisexuality of the otherwise archly conservative race. The narrator has been sent to the planet to assess and invite its people to join the league of worlds known as the Ekumen. The unmitigated bleakness of Winter complements Genly’s unembellished style as he compiles his mission report. The harsh conditions and a mistrust shared by the proud inhabitants mean that he never feels truly comfortable and a tension obtains that is felt throughout the account. Like a musical string taughtened, it plays and can be plucked, but it might equally snap. Genly’s candid report fascinates for being as subjective as it is objective: for being whole. He struggles to assimilate the––to him––bizarre sexual gender fluidity of the Gethenians and which causes them to switch between male and female. It undermines Genly’s capacity to act. He cannot rely on a constant, gender-based response to his self-identity, which he recognizes is based on his own maleness, since the natural parameters of sexual behaviour and interaction are utterly changeable. “A man wants his virility regarded, a woman wants her femininity appreciated, however indirect and subtle the indications of regard and appreciation. On Winter they will not exist. One is respected and judged only as a human being. It is an appalling experience.” The more he investigates and the longer his stay, the more the emissary/observer will be drawn into events. Ostensibly the representative of a more advanced and magnanimous civilization (in this, the Ekumen has a significant parallel with Iaian M. Banks’s “Culture”), Genly Ai feels increasingly unsympathetic and alienated, despairing of his one potentially promising contact, the reserved and unreadable Estraven. Yet it will be Therem Harth rem ir Estraven who proves to be the great reward to anyone who reads Le Guin’s singular tale. Estraven’s melancholic taciturnity is evidence of that carefulness of honesty which prefers silence to inauthentic speech, or to seeking advantage. “To oppose vulgarity is inevitably to be vulgar. You must go somewhere else; you must have another goal; then you walk a different road.” He-she is also wary of the considerable risk they are taking in befriending Ai, not only politically. “A profound love between two people involves, after all, the power and chance of doing profound hurt." “The unexpected is what makes life possible,” says the Gethenian, and it is through the character of Estraven that a revelation will come to Genly Ai. He will see the love that is unfathomable power able to be opposites at once. The left hand and the right are distinct and conjoined. “Fear, courage. Cold, warmth. Female, male. It is yourself, Therem. Both and one. A shadow on snow." One of my all-time Phil Dick faves, zipped along by his keen sense of fun, is a fine example of how well-suited science fiction is to expounding psychosocial truths.

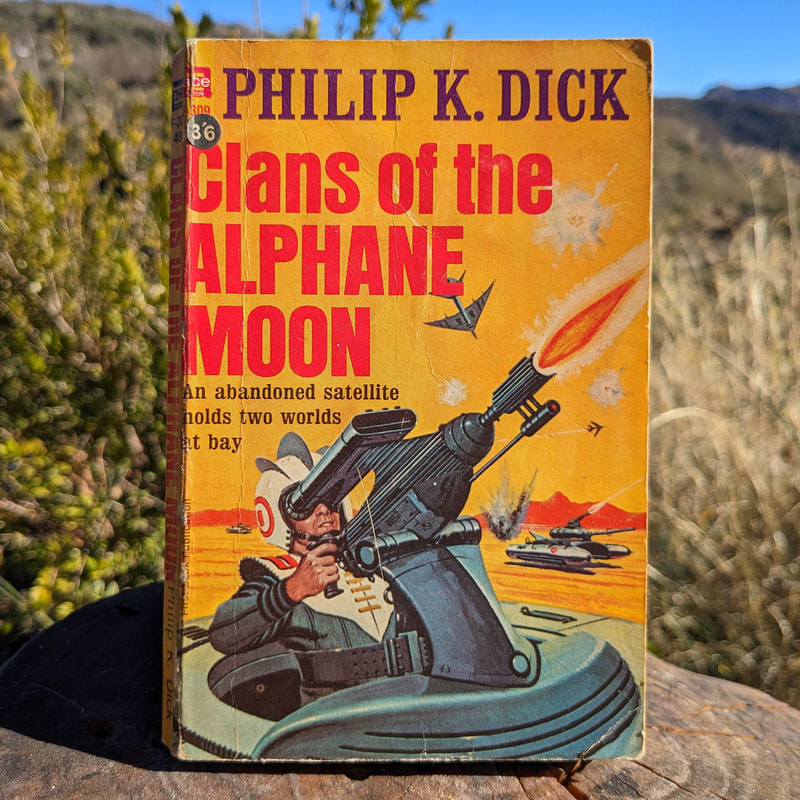

Inmates of an asylum for the insane are transported to an uninhabited moon, only for their doctors’ rocket ship never to make it there, leaving them to form their own society, which they run in accordance with their particular mental disorders. The paranoid assume supreme leadership, the manics are the military, the schizos are visionaries and the OCD’s dedicate themselves to administrative detail and the status quo. I mean, just look around you! 😛 Make the clans supporting actors to a murderous marital spat and away you go. Me, I would have adored the book forever just for featuring a telepathic Ganymedean slime mould called Lord Running Clam. Put a spell on me from the outset.

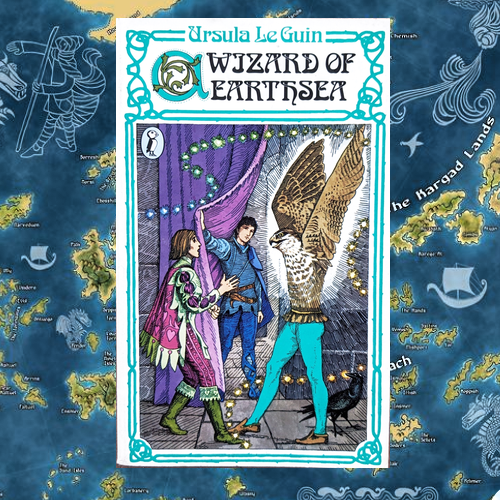

There is something about Le Guin’s writing that I have always found captivating and it is this: she stays faithful to the story and always speaks her truth, which is no small matter. One has to be open to and in touch with it. Then she communicates in the timeless imagery of the unconscious which is myth. In her particular, unadorned style, the narrative moves forward with such simple assurance that it lends an aura of inevitability to events. The author hadn’t read Jung when she wrote this and subsequent books in the cycle, and didn’t need to, of course. She trusted her native intuition and A Wizard of Earthsea took on archetypal attributes naturally. She knew the importance of secrets. It makes the story particularly apt for those entering adulthood, although the mythic quality and Le Guin’s depth will speak to the old soul in anyone. I read this fantasy series when I was about thirty and felt its strong mystery and truth then. The seriousness with which the dwellers of Gont take the gift of the power of spells matches Le Guin’s own. For all that she enjoyed writing the fantasy, she never took it lightly. To make “worlds out of words” is truly a power. “Obviously, to me, words do make magic,” she said. And the greater the power to work magic, the greater the mage’s responsibility, as Ged will discover. It cannot make him, but it can break him. Where Le Guin differs from other fantasy writers, even a great one like Tolkien, is in eschewing the military battleground and denying it centre stage for good and evil to fight it out. Such a denouement was too facile and unsatisfactory in her view. In the world that she creates, there is an imbalance and it needs to be put right. Instead of witnessing armies assemble, we feel the hidden conflict in Ged’s own person. The shadow passes over our hearts, and the real story is of the self. There was a before and an after in my reading life and its name was Philip K. Dick.

The dam of priggish reading was burst, the snob was snubbed, and I tipped over into a sanguine land of wild ideas. To enter the cosmic open-mindedness of Dick’s imagination was like stepping into sunlight from the drab and stodgy intellectuality of my Britishness. From monochrome to colour. For intelligent fun there is no one like PKD. That his familiar milieu and point of departure was 1950s & 1960s California just made it more attractive. That on its own for me represented a can-do place of opportunity in contrast to restrictive, inhibited, anaemic England. Then, of course, Dick starts reimagining. In Philip K. Dick I discovered serious playfulness: a writer free to do and think whatever he liked, while taking this privilege responsibly. What I like about his novels is that he gives his characters a world that is somehow competent. It is non-kafkaesque. However outlandish the reality may be, there is no undermining of its fabric. The protagonists are in a fix but not guilty of unnamed sins or crimes, nor are they grievously ill-used. When the world is competent, you feel that things can happen. It gives them a chance to act and achieve something. He likes his characters and is compassionate, or at least fair, to the least of them. In this 1968 novel, ambiguities concerning human and android are clear yet never laboured. You don’t have to live in a cybernetic age to appreciate them: even if the growing existential threat from AI ratchets up the credibility of lethal robots, where the plot really works is on a deeper level of the psyche, and what it means to be human. The Mercerist empathy boxes offering collective experience in suffering are a tremendously suggestive idea. The book did, of course, find cinematic expression as “Blade Runner,” simply my favourite movie of all time 😊 |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed