South America 1987

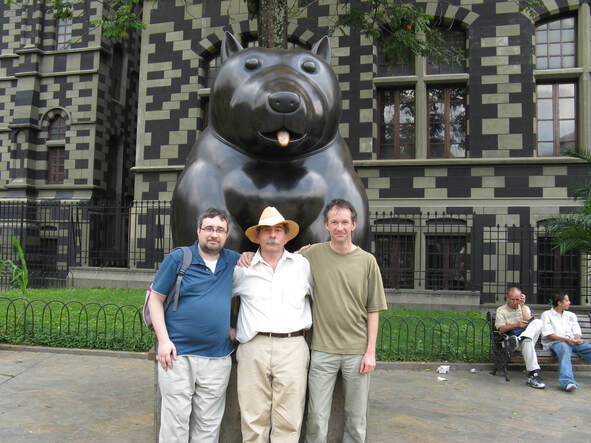

Bogotá, Nov ’87

A simple pot in the Gold Museum is a living presence. In the shape of a halved corncob—the sun god’s golden fruit and ubiquitous gift to mankind— the pot was a vessel for the lime which catalyzes stimulants in chewed coca leaf, instrumental in a ritual re-entry to the realm before man and animal, before time began.

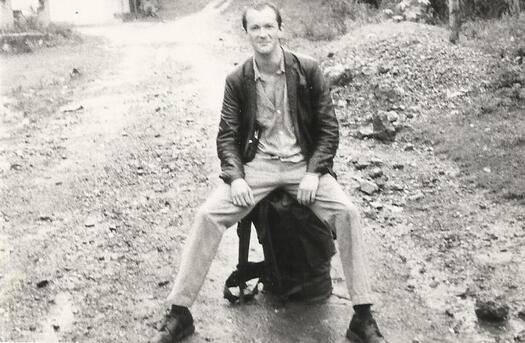

At Constanza’s family home, within the precinct of their school with its high walls and armed guards, I am cared for and going nowhere. The girls, wanting to show me the best of the city, take me to the shopping mall. I book a bus ticket to Cali, and it all begins.

Pereira villaje. On the wall: “Yo soy el recuerdo de un hombre que no fue.” The long black Cadillac, rejoicing in swept-back wings and coupé, was a hearse. Before our bus leaves the station, we are boarded by orange acolytes wanting to sell us AIDS leaflets and joss sticks. “Muchas gracias por su atención y Hare Krishna.”

A simple pot in the Gold Museum is a living presence. In the shape of a halved corncob—the sun god’s golden fruit and ubiquitous gift to mankind— the pot was a vessel for the lime which catalyzes stimulants in chewed coca leaf, instrumental in a ritual re-entry to the realm before man and animal, before time began.

At Constanza’s family home, within the precinct of their school with its high walls and armed guards, I am cared for and going nowhere. The girls, wanting to show me the best of the city, take me to the shopping mall. I book a bus ticket to Cali, and it all begins.

Pereira villaje. On the wall: “Yo soy el recuerdo de un hombre que no fue.” The long black Cadillac, rejoicing in swept-back wings and coupé, was a hearse. Before our bus leaves the station, we are boarded by orange acolytes wanting to sell us AIDS leaflets and joss sticks. “Muchas gracias por su atención y Hare Krishna.”

Popayán, Colombia

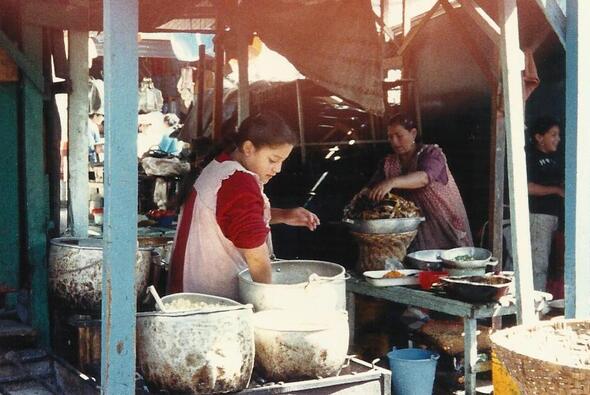

Empanadas and coffee. Silvia village in the rain. Two brothers, one a teacher, were killed this morning by police. Things are getting worse. Not long ago, in Cali, impromptu death squads were cleaning the streets of bums and homosexuals, and in Medellin, another group of men in plain clothes entered the Communist Youth building, put four men against the wall and gunned them down. The two armed policemen standing guard outside remained at their posts, deaf and blind, while the killers got away.

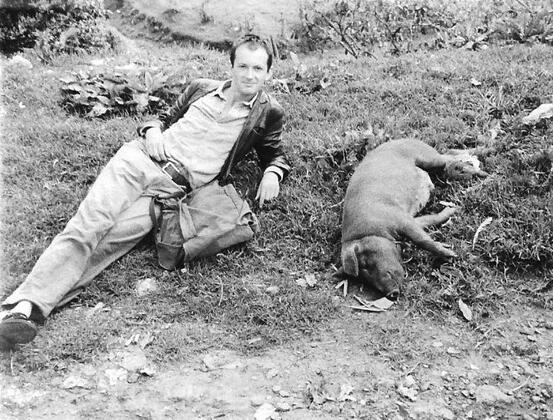

Half-gutted pigs’ heads. At the Gnostic pyramid, fire is represented by swords, earth by white dust, water by flowers, air by a condor feather, our earthly span by a broken alarm clock and the word of God by a hen.

Empanadas and coffee. Silvia village in the rain. Two brothers, one a teacher, were killed this morning by police. Things are getting worse. Not long ago, in Cali, impromptu death squads were cleaning the streets of bums and homosexuals, and in Medellin, another group of men in plain clothes entered the Communist Youth building, put four men against the wall and gunned them down. The two armed policemen standing guard outside remained at their posts, deaf and blind, while the killers got away.

Half-gutted pigs’ heads. At the Gnostic pyramid, fire is represented by swords, earth by white dust, water by flowers, air by a condor feather, our earthly span by a broken alarm clock and the word of God by a hen.

In the Popayán bookshop, the owner is still waiting for the whisky that Martha and I went to fetch.

The magician at La Plata claimed to know how to catch birds, how to make a girl dance naked, and how to get everyone in the house to leave: sprinkle a powdered magnet in the four corners.

The magician at La Plata claimed to know how to catch birds, how to make a girl dance naked, and how to get everyone in the house to leave: sprinkle a powdered magnet in the four corners.

Weather-eaten gods line the way at San Andrés. You don’t see the openings in the earth until you are almost upon them. I let myself down into the gaping mouth of the underground chambers. There, in the darkness, holds a silence that once celebrated ceremony.

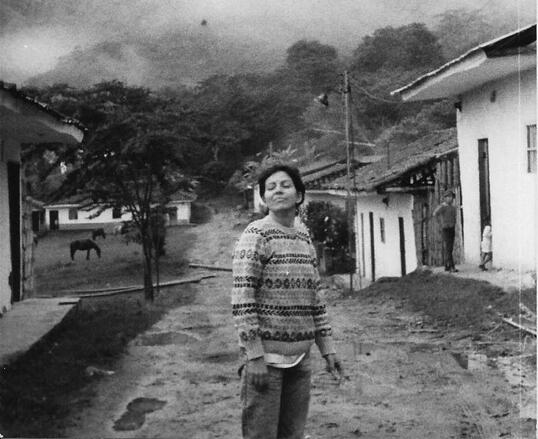

“I like to bite you,” says Martha.

“I like to bite you,” says Martha.

Quito, Dec ’87

I see my first llama whilst waiting to get into the prison. I am here to visit Danny, whose name and appreciation of visits I found scrawled on my hotel room wall. Etiquette demands that I bribe my way in. I could just give it to him, but the guard insists that I pass the 50-sucre note to him inside my passport. There is no prison uniform so that to the visitor, once inside, warder and inmate are indistinguishable. The French prison has stood 150 years and Danny has sat in there for eight of them. It would have been less if he hadn’t done a bunk twice; once over the wall, once under it, when he got quite far by boat before being caught. I brought cigarettes. The US Embassy had brought him a year-old newspaper from his native Hawaii. Danny tells me that the guerrilla organizations of Colombia, Peru and Ecuador have joined forces with the base at Ayacucho. He is due out in just a few weeks. “You must be pleased,” I say. “Not really,” he says.

At the Ministry of Defence there are kids running around inside. I am attempting to blag my way on board a military supply plane to the Galapagos. I am not searched going in and I get the chance to brandish a forged letter before an official, making myself out as a biology student. He sends me packing, but not for the plane.

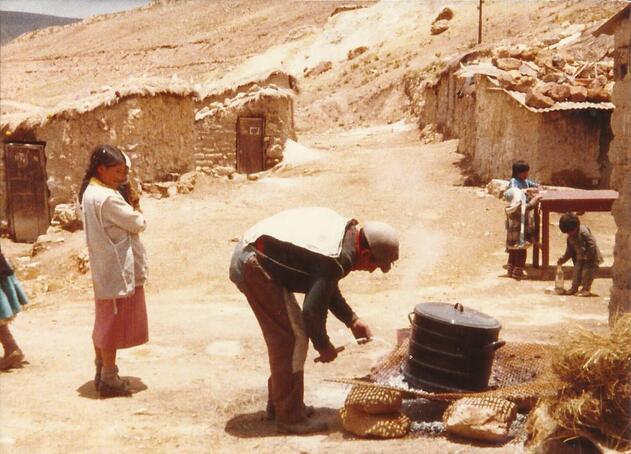

New Zealander Phil, who is cycling through the Andes, cooks in his room on a camping stove. I learn to play hat football. It is the closest I come to having any sense of direction.

I see my first llama whilst waiting to get into the prison. I am here to visit Danny, whose name and appreciation of visits I found scrawled on my hotel room wall. Etiquette demands that I bribe my way in. I could just give it to him, but the guard insists that I pass the 50-sucre note to him inside my passport. There is no prison uniform so that to the visitor, once inside, warder and inmate are indistinguishable. The French prison has stood 150 years and Danny has sat in there for eight of them. It would have been less if he hadn’t done a bunk twice; once over the wall, once under it, when he got quite far by boat before being caught. I brought cigarettes. The US Embassy had brought him a year-old newspaper from his native Hawaii. Danny tells me that the guerrilla organizations of Colombia, Peru and Ecuador have joined forces with the base at Ayacucho. He is due out in just a few weeks. “You must be pleased,” I say. “Not really,” he says.

At the Ministry of Defence there are kids running around inside. I am attempting to blag my way on board a military supply plane to the Galapagos. I am not searched going in and I get the chance to brandish a forged letter before an official, making myself out as a biology student. He sends me packing, but not for the plane.

New Zealander Phil, who is cycling through the Andes, cooks in his room on a camping stove. I learn to play hat football. It is the closest I come to having any sense of direction.

Esmeraldas stinks of crime, violence, corruption and the rotting, fly-ridden rubbish still lying around after a garbage strike. Urchins and stories of stilettos: a blade so thin and narrow that you feel little as it is slid into you two, three times. It fucks your liver and you die.

At Muisne, my cabin is lovable. Sand crabs and more stars than I have ever showered under.

On the Pisco bus, Bertholt saw one chap piss in his hat, wring it out and put it back on his head so that urine dripped down his cheeks and temples. He was once seated near the bog on a night train in India. All night, a steady stream of piss and liquid shit passed through the carriage and past them. All the carriage windows were jammed open and when they rose from their hard bench seats in the morning, they found their silhouettes on the wall behind them.

Crusoe rarely thought of leaving. When the chance came and he took it, it was no escape.

On the Quieniende –Quito bus we are fumigated for a banana pest.

At the Casas de Cambio, the cashier copies down the name on your passport. In this way, I become Guy Drahut and Grey Simpson.

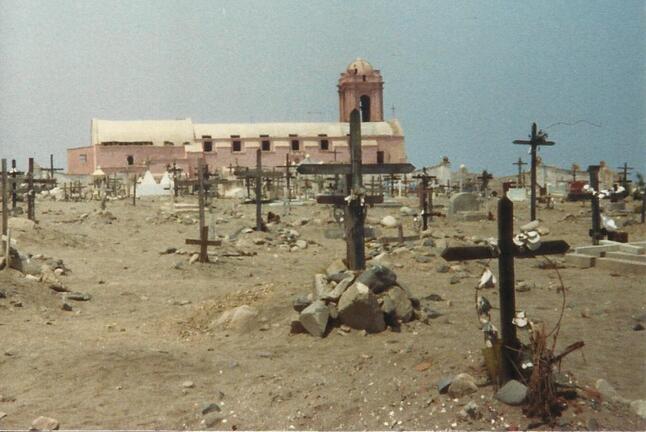

Cuenca. Streaming, boiling clouds. Black pigs. White, pigeon-holed cemeteries. People suck mangos all day. I feel justified at staying a-bed and getting a later bus once we pass the 9 o’clock in a ditch. Three vehicles off the road today.

A quicksilver taste of fear prickles the tongue at the threshold to every place of misfortune. When I numb the tongue, I fear instead the confusion of not knowing the nature or extent of my self-deceptions.

Piles of rubble in the streets, none approaching completion.

The lemon-domed tower of San Blas. The constitutional right of the shoeblack to look with reproach at your shoes.

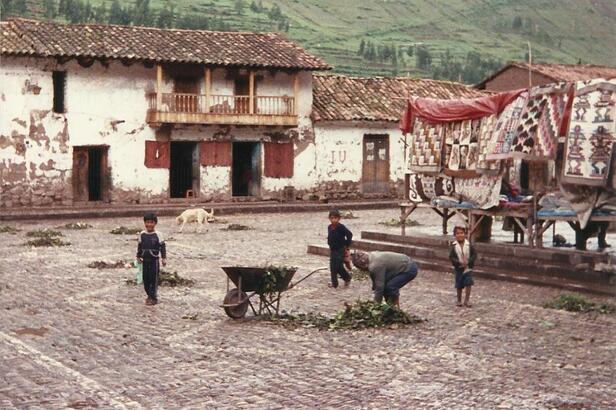

Peru Dec ’87

After hour after hour of nothing but desert, the bus pulls into a throbbing city. It is Chiclayo. The Hostal San Ramón, however insecure, costs $2 a room and what do I find? My own bathroom, with a shower and a toilet that works, as does the light. There is bog paper. There are two mirrors, a parquet floor and a cloak stand on which I hang my hat. Towels are laid out, the sheets are white cotton and the pillow gives pleasingly. There’s even a tooth glass, for Christ’s sakes. I expect the room to be robbed the moment I go out. The desk clerk asks if I am Roman.

Pimentel has an old wooden pier and a dirty smell up your nose: proper seaside! A colectivo playing a Latin version of Dusty’s “I only wanna be with you” deposits a skinny white Englishman on the hot sand, where he walks across to the sea darkened only by a scruffy beard and navy-blue Y-fronts. There was once a functioning train to the pier but Pimentel is in a state of dereliction and demolition, except for what looks like a cricket pavilion and, beyond a navy squaddie behind sand bags with a machine gun, the beach houses of Peru’s smart set.

Peruvian courtesy strikes me as evidence of a social maturity.

And there goes a gold VW taxi.

At Muisne, my cabin is lovable. Sand crabs and more stars than I have ever showered under.

On the Pisco bus, Bertholt saw one chap piss in his hat, wring it out and put it back on his head so that urine dripped down his cheeks and temples. He was once seated near the bog on a night train in India. All night, a steady stream of piss and liquid shit passed through the carriage and past them. All the carriage windows were jammed open and when they rose from their hard bench seats in the morning, they found their silhouettes on the wall behind them.

Crusoe rarely thought of leaving. When the chance came and he took it, it was no escape.

On the Quieniende –Quito bus we are fumigated for a banana pest.

At the Casas de Cambio, the cashier copies down the name on your passport. In this way, I become Guy Drahut and Grey Simpson.

Cuenca. Streaming, boiling clouds. Black pigs. White, pigeon-holed cemeteries. People suck mangos all day. I feel justified at staying a-bed and getting a later bus once we pass the 9 o’clock in a ditch. Three vehicles off the road today.

A quicksilver taste of fear prickles the tongue at the threshold to every place of misfortune. When I numb the tongue, I fear instead the confusion of not knowing the nature or extent of my self-deceptions.

Piles of rubble in the streets, none approaching completion.

The lemon-domed tower of San Blas. The constitutional right of the shoeblack to look with reproach at your shoes.

Peru Dec ’87

After hour after hour of nothing but desert, the bus pulls into a throbbing city. It is Chiclayo. The Hostal San Ramón, however insecure, costs $2 a room and what do I find? My own bathroom, with a shower and a toilet that works, as does the light. There is bog paper. There are two mirrors, a parquet floor and a cloak stand on which I hang my hat. Towels are laid out, the sheets are white cotton and the pillow gives pleasingly. There’s even a tooth glass, for Christ’s sakes. I expect the room to be robbed the moment I go out. The desk clerk asks if I am Roman.

Pimentel has an old wooden pier and a dirty smell up your nose: proper seaside! A colectivo playing a Latin version of Dusty’s “I only wanna be with you” deposits a skinny white Englishman on the hot sand, where he walks across to the sea darkened only by a scruffy beard and navy-blue Y-fronts. There was once a functioning train to the pier but Pimentel is in a state of dereliction and demolition, except for what looks like a cricket pavilion and, beyond a navy squaddie behind sand bags with a machine gun, the beach houses of Peru’s smart set.

Peruvian courtesy strikes me as evidence of a social maturity.

And there goes a gold VW taxi.

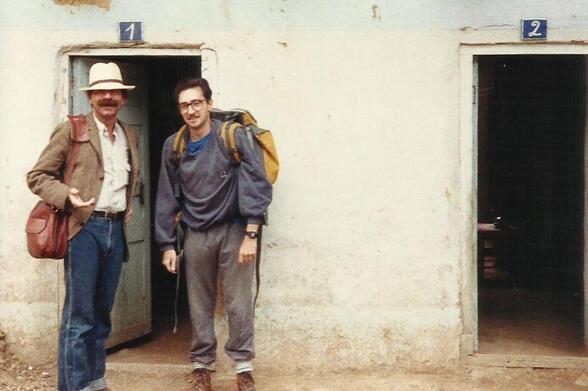

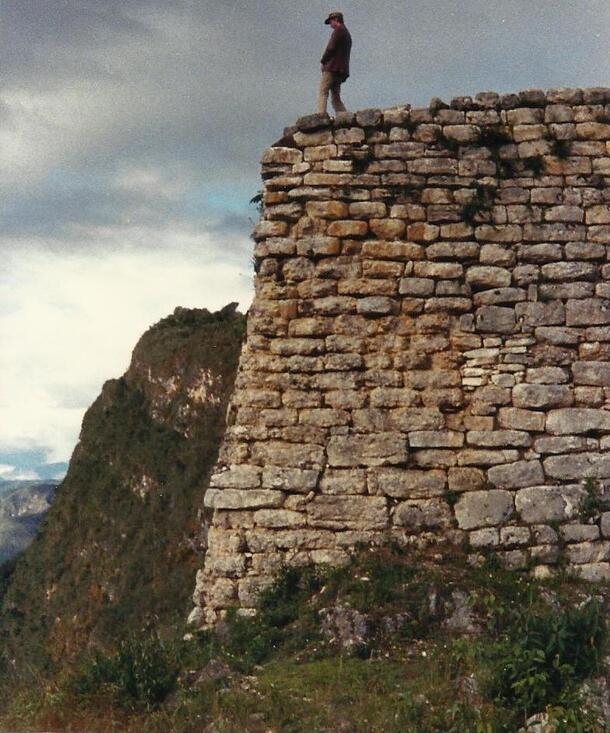

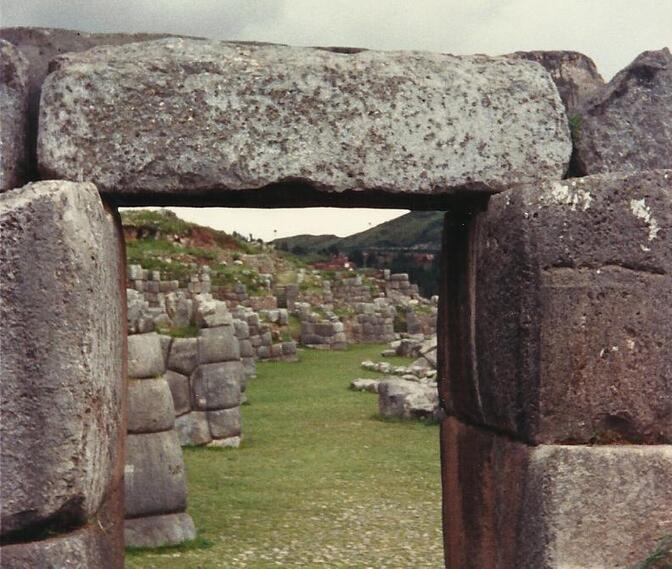

Kuelap

In the truck from Tingo, on the narrow cliff road, I see my first condor. We — a certain American and Englishman I have met — are dropped off at the base of a great hill and, brave warriors that we are, undertake the arduous ascent to the ruined pre-Incan fortress that Lonely Planet gives a mention to, feeling most intrepid until children run up past us on their way to school. On reaching the ancient hilltop ruins, the doughty explorers are confronted by a locked door. This would have been an end to their quest but for a family living at a nearby cottage has the key and the woman lets us in. We roam the fortress and don't find any gold. I guess it is too well hid. There are, though, human bones and a headiness of the altitude.

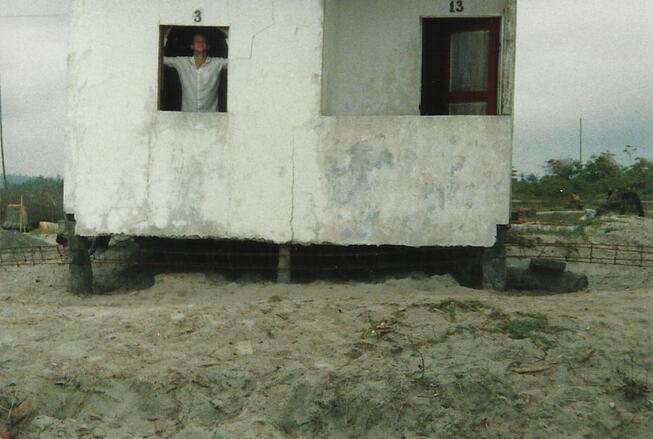

The only place to overnight is a cabin built for a government archeologist who rarely comes. The family with the key to Kuelap kill and cook a chicken we singled out. We frown at how little meat ends up on our plates and suspect that the family had a far better meal that evening than we did.

In the truck from Tingo, on the narrow cliff road, I see my first condor. We — a certain American and Englishman I have met — are dropped off at the base of a great hill and, brave warriors that we are, undertake the arduous ascent to the ruined pre-Incan fortress that Lonely Planet gives a mention to, feeling most intrepid until children run up past us on their way to school. On reaching the ancient hilltop ruins, the doughty explorers are confronted by a locked door. This would have been an end to their quest but for a family living at a nearby cottage has the key and the woman lets us in. We roam the fortress and don't find any gold. I guess it is too well hid. There are, though, human bones and a headiness of the altitude.

The only place to overnight is a cabin built for a government archeologist who rarely comes. The family with the key to Kuelap kill and cook a chicken we singled out. We frown at how little meat ends up on our plates and suspect that the family had a far better meal that evening than we did.

Coming back, we get stranded at the one-horse and no bus town of Tingo. The only public space is a mean little bar where we are landed with the local police getting drunk for New Year’s Eve. The only phrase they can pronounce, ad nauseum, is “Despedimos ocho-siete, recibimos ocho-ocho.” When they go to toast the Peruvian president, “Alan...”, they cannot remember the rest of his name. It is doubly excruciating for me as I am on antibiotics and cannot numb myself with their liquor.

1988

We get as far as Chachapoyas, ready to leave, and get stuck again. There are no planes out. Playing pool in the upstairs room at the hotel is the only available pastime. It is like being in a 1950s movie.

The end of year festivities finally over, everyone and his cousin are heading home. The airport is swamped by visiting Peruvians and their double-body-size bulging baggage, all crowding for the one and only, very overbooked flight out of Chachapoyas.

Faced with the seething mass, Ron and Ian, ticketless in any case, decamp to look for a bus out of the place. Young Germans say to them in a strong accent: “So you are surrendering?”

Released through the bottleneck of the airport gate, the horde storms the little plane across the tarmac and I dash with them for all I am worth. Somehow I manage to get on and into a seat, gripping the arms and prepared to repel all comers. The plane fills in seconds. The aisle is chockablock with bulky packages, a crate of hens. The only item that is refused, and that the stewardess obliges a man to remove from the aircraft, is a canister that he is trying to fit into an overhead locker. The cap’s thread is worn and held in place infirmly by a scrap of torn polythene, and the petrol leaks.

The flight to the coast takes about 40 minutes, whereas the overland route is slow and laborious. For every minute that I sit on the plane, it will take Ian and Ron an hour by a variety of open-top trucks and rickety buses. They will find me two days later lying by a Chiclayo hostal pool, yet our new friendship will survive this and more. When I get back to England and look at my credit card bill, I will see that the devaluing peso price for the flight translated to eleven pounds.

Chiclayo

A grandmother counts the grains in a mound of rice.

I am talking with another Englishman about Captain Pugwash. I do his head in when I mention a character he didn’t know about called Master Bates, until he gets me with one that I know nothing of: Seaman Staines. Halcyon days of British broadcasting for children. How did they get away with it?

The end of year festivities finally over, everyone and his cousin are heading home. The airport is swamped by visiting Peruvians and their double-body-size bulging baggage, all crowding for the one and only, very overbooked flight out of Chachapoyas.

Faced with the seething mass, Ron and Ian, ticketless in any case, decamp to look for a bus out of the place. Young Germans say to them in a strong accent: “So you are surrendering?”

Released through the bottleneck of the airport gate, the horde storms the little plane across the tarmac and I dash with them for all I am worth. Somehow I manage to get on and into a seat, gripping the arms and prepared to repel all comers. The plane fills in seconds. The aisle is chockablock with bulky packages, a crate of hens. The only item that is refused, and that the stewardess obliges a man to remove from the aircraft, is a canister that he is trying to fit into an overhead locker. The cap’s thread is worn and held in place infirmly by a scrap of torn polythene, and the petrol leaks.

The flight to the coast takes about 40 minutes, whereas the overland route is slow and laborious. For every minute that I sit on the plane, it will take Ian and Ron an hour by a variety of open-top trucks and rickety buses. They will find me two days later lying by a Chiclayo hostal pool, yet our new friendship will survive this and more. When I get back to England and look at my credit card bill, I will see that the devaluing peso price for the flight translated to eleven pounds.

Chiclayo

A grandmother counts the grains in a mound of rice.

I am talking with another Englishman about Captain Pugwash. I do his head in when I mention a character he didn’t know about called Master Bates, until he gets me with one that I know nothing of: Seaman Staines. Halcyon days of British broadcasting for children. How did they get away with it?

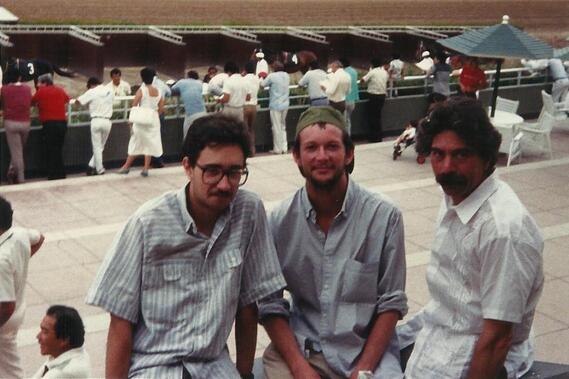

Lima

Accompanied by cockroaches, we cross Hotel Bolivar’s cafeteria floor to our stretch limo taxi, a ’56 Cadillac, which only cost 25% more than a regular one, and drive to the races at Monterrico. By virtue of being first-world scumbags, we are admitted to the Members’ Enclosure. Princesa Loca wins for the first race for me.

Tear gas explodes and a machine gun rattles down near the 2 de mayo, but no one is interested. I tell dark and comely Vicky, “you have hair like a horse running, your mouth is like unto a river, your eyes are gazelles, the wind herself is no smoother than the smoothness of your skin.”

The traffic cops warble with their whistles.

Consider the profits of the Coca Cola company. In Peru, where it is made under licence, a restaurant can sell a coke for the equivalent of eight pence.

Cuzco

Last month the Sendero Luminoso took over Mass in the cathedral. They were lucky to find it open.

I lose count of the times we are stopped and checked, and occasionally frisked, by police or army. Each time, every passenger has to fill out an ID & personal details form. It is getting tiresome and I am making up professions. The most recent: tachometer and cement mixer.

The Deepest Sleep

The deepest sleep ever recorded was that slept by María-Lucía Tamale of the Hostal Suecia in Cuzco, Peru, on the night of 19th January 1988, who at one point plumbed a full 403 miles, deaf even to the beserk knocking of a locked-out French tourist.

Kneel down in the warm baths’ soft gravel in Aguas Calientes. You have climbed up the gorge from Macho Picchu and the baths are set into the rock, away from the rapids and the dogs. Roots dangle, ferns are ferns, black water drips down the rock into the hot pool. Look back down the gorge and you are confronted by a colossal pyramid, its tip in the clouds.

Accompanied by cockroaches, we cross Hotel Bolivar’s cafeteria floor to our stretch limo taxi, a ’56 Cadillac, which only cost 25% more than a regular one, and drive to the races at Monterrico. By virtue of being first-world scumbags, we are admitted to the Members’ Enclosure. Princesa Loca wins for the first race for me.

Tear gas explodes and a machine gun rattles down near the 2 de mayo, but no one is interested. I tell dark and comely Vicky, “you have hair like a horse running, your mouth is like unto a river, your eyes are gazelles, the wind herself is no smoother than the smoothness of your skin.”

The traffic cops warble with their whistles.

Consider the profits of the Coca Cola company. In Peru, where it is made under licence, a restaurant can sell a coke for the equivalent of eight pence.

Cuzco

Last month the Sendero Luminoso took over Mass in the cathedral. They were lucky to find it open.

I lose count of the times we are stopped and checked, and occasionally frisked, by police or army. Each time, every passenger has to fill out an ID & personal details form. It is getting tiresome and I am making up professions. The most recent: tachometer and cement mixer.

The Deepest Sleep

The deepest sleep ever recorded was that slept by María-Lucía Tamale of the Hostal Suecia in Cuzco, Peru, on the night of 19th January 1988, who at one point plumbed a full 403 miles, deaf even to the beserk knocking of a locked-out French tourist.

Kneel down in the warm baths’ soft gravel in Aguas Calientes. You have climbed up the gorge from Macho Picchu and the baths are set into the rock, away from the rapids and the dogs. Roots dangle, ferns are ferns, black water drips down the rock into the hot pool. Look back down the gorge and you are confronted by a colossal pyramid, its tip in the clouds.

In a Cuzco pharmacy, the weighing machine doubles as an oracle:

“Where will I spend the rest of my life?”

“En su vejez, viajando.”

We chug across Titicaca to Isla del Sol. This is a Quechua cooperative where the men wander the island all day crocheting belts. A boy cradling eggs in his hands greets us by making a rolling grrrrrr sound. Ian and I respond in like fashion, chopping forked fingers at him for good measure.

“Where will I spend the rest of my life?”

“En su vejez, viajando.”

We chug across Titicaca to Isla del Sol. This is a Quechua cooperative where the men wander the island all day crocheting belts. A boy cradling eggs in his hands greets us by making a rolling grrrrrr sound. Ian and I respond in like fashion, chopping forked fingers at him for good measure.

In la Paz, the miners’ marches are led by the women. The men’s pace is tired and their voices have lost hope. The military watch on as they congregate outside San Francisco cathedral for a bowl of hot soup.

More police checks, more forms to be filled, and my professional development evinces new occupations and responsibilities: warlock, gesticulator, minor deity.

A bus stands on a thin, high road indicating direction. Behind the bus, six military police are inspecting the baggage they have ordered off the transport. Dust and broken rock stretch out into the heat haze. The silence is abruptly broken by grunts and yelps as the policemen are assailed by squirts and jets from bottles of shampoo, sun tan lotion and contact lens solution, which have all risen several thousand feet during the journey and now let fly with all the relief and unselfconsciousness of a constipated Bolivian.

More police checks, more forms to be filled, and my professional development evinces new occupations and responsibilities: warlock, gesticulator, minor deity.

A bus stands on a thin, high road indicating direction. Behind the bus, six military police are inspecting the baggage they have ordered off the transport. Dust and broken rock stretch out into the heat haze. The silence is abruptly broken by grunts and yelps as the policemen are assailed by squirts and jets from bottles of shampoo, sun tan lotion and contact lens solution, which have all risen several thousand feet during the journey and now let fly with all the relief and unselfconsciousness of a constipated Bolivian.

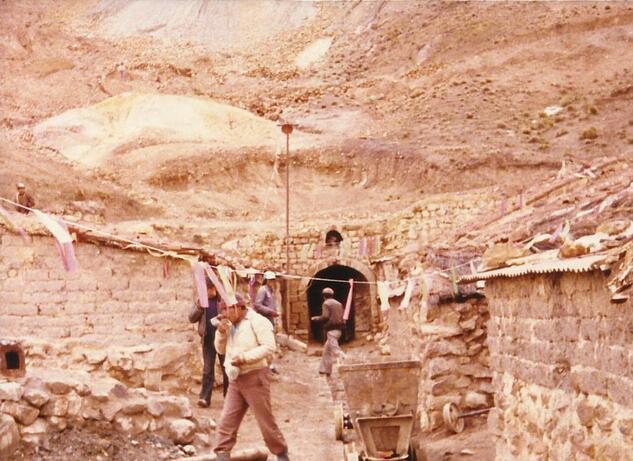

Potosí

Once we have chewed our coca leaves and El Tío has been decorated and ministered to with singani and a cigarette stuck in the ugly little devil’s mouth, we descend the mine, decked out in streamers and confetti. They are celebrating el Día de los Compadres. The ghastly black mountain that squats above Potosí is riddled with five thousand mines. A riddle of darkness and a lottery of death. Over four hundred years, it swallowed eight million men to finance Spain’s wars with its silver and it is hungry still.

One can barely breathe down there. The mine we are visiting is worked by a cooperative of some eighty men. Unlike the state-run mines, there is no lift transport for men and ore, no machinery to dig with, no ventilation shafts, no electric lamps and no salary (be it only B$60/US$30 a month). Instead, each man is paid according to the quality and quantity of ore that he hacks out and carries on his back, 35 kg at a time, up to the surface. It is up to each man to choose his spot: there are no engineers to detect veins for him, only El Tío to grant or withhold favour and fortune. In town the men are Catholic, but this is the underworld. In July, they sacrifice a llama to the earth spirit, throwing its warm blood over the shaft entrance.

In the confined space of the fifth level, 150 metres below ground and yet over 4,000 metres high, the temperature can reach 42°C. There being no ventilation, these miners wear no face masks or they wouldn’t be able to breathe at all, two hours masticating coca leaf previously or no. The miner will work from ten to one, stop to chew coca for another hour (he doesn’t lunch) and then work on until six, perhaps even nine. There is tin, lead, a little low-grade silver, zinc. If a miner hits nothing for weeks, he is paid nothing. He must rely on a loan from the cooperative to maintain his family and buy carbide for his lamp & dynamite for blasting. A miner who starts his working life at twelve will succumb to death by silicosis before he reaches forty. Or it will be a rock fall, sulphurous gases, or poison fumes from the dynamite and carbide.

Once we have chewed our coca leaves and El Tío has been decorated and ministered to with singani and a cigarette stuck in the ugly little devil’s mouth, we descend the mine, decked out in streamers and confetti. They are celebrating el Día de los Compadres. The ghastly black mountain that squats above Potosí is riddled with five thousand mines. A riddle of darkness and a lottery of death. Over four hundred years, it swallowed eight million men to finance Spain’s wars with its silver and it is hungry still.

One can barely breathe down there. The mine we are visiting is worked by a cooperative of some eighty men. Unlike the state-run mines, there is no lift transport for men and ore, no machinery to dig with, no ventilation shafts, no electric lamps and no salary (be it only B$60/US$30 a month). Instead, each man is paid according to the quality and quantity of ore that he hacks out and carries on his back, 35 kg at a time, up to the surface. It is up to each man to choose his spot: there are no engineers to detect veins for him, only El Tío to grant or withhold favour and fortune. In town the men are Catholic, but this is the underworld. In July, they sacrifice a llama to the earth spirit, throwing its warm blood over the shaft entrance.

In the confined space of the fifth level, 150 metres below ground and yet over 4,000 metres high, the temperature can reach 42°C. There being no ventilation, these miners wear no face masks or they wouldn’t be able to breathe at all, two hours masticating coca leaf previously or no. The miner will work from ten to one, stop to chew coca for another hour (he doesn’t lunch) and then work on until six, perhaps even nine. There is tin, lead, a little low-grade silver, zinc. If a miner hits nothing for weeks, he is paid nothing. He must rely on a loan from the cooperative to maintain his family and buy carbide for his lamp & dynamite for blasting. A miner who starts his working life at twelve will succumb to death by silicosis before he reaches forty. Or it will be a rock fall, sulphurous gases, or poison fumes from the dynamite and carbide.

There are few causes for celebration. Outside we drink chicha from an oil drum. An old miner who fought in the revolution of ’52 chucks a stick of dynamite it as if it was a firework, his wife smiling alongside, holding a baby. I do not mind when a little debris falls on my head.

Buenos Aires, Feb ’88

Shortly before the Malvinas conflict, a former school friend of Alicia’s brother approached him for help. Supposedly a bishop’s chauffeur, he confessed that the job was a cover and that he had been involved in the killings and torturing of the dirty war. At this time, the military were trying to do away with those like him who had participated or witnessed too much. Her brother thought of stowing him in a newspaper truck headed for the border, but before anything could be arranged, the Junta had occupied the Malvinas, the British taskforce was underway and the man found himself conscripted. He was put aboard a ship bound for the islands along with a number of his “ex-colleagues.” Who found they had unexpected company.

Wanting to make use of captured machine guns that their own men didn’t know how to operate, the military offered the original owners, jailed guerrillas, a free pardon if they would go fight in the Malvinas and show them what the weapon could do. The guerrillas thus found themselves on a ship together with their former jailers and torturers. The intention was clear. Being confined in close quarters on the same ship, it was supposed that the Junta’s political opponents and their embarrassing liabilities would massacre each other en route. It indicates how serious the generals were about winning the conflict.

The conduct of the Argentine military in the campaign was always cowardly, Alicia tells me. On another ship, they transported 100 dogos (a hunting dog) which they sent running across a no man’s land to attack the British machine gunners. One can imagine how that ended. They otherwise sent out young boys doing national service to be killed by professional soldiers, while officers excused themselves on grounds of ill-health, sometimes shooting themselves in the foot. As for the represor ex-schoolfriend, the bastard is probably still alive somewhere. The torturers and the tortured never clashed on the ship in the intended bloodbath and none of them saw action, either, thanks to a timely surrender at Stanley. It cuts both ways. Alicia has a cat she calls Belgrano. When she tells it off, it speeds to the bedroom to pee in her shoes.

Shortly before the Malvinas conflict, a former school friend of Alicia’s brother approached him for help. Supposedly a bishop’s chauffeur, he confessed that the job was a cover and that he had been involved in the killings and torturing of the dirty war. At this time, the military were trying to do away with those like him who had participated or witnessed too much. Her brother thought of stowing him in a newspaper truck headed for the border, but before anything could be arranged, the Junta had occupied the Malvinas, the British taskforce was underway and the man found himself conscripted. He was put aboard a ship bound for the islands along with a number of his “ex-colleagues.” Who found they had unexpected company.

Wanting to make use of captured machine guns that their own men didn’t know how to operate, the military offered the original owners, jailed guerrillas, a free pardon if they would go fight in the Malvinas and show them what the weapon could do. The guerrillas thus found themselves on a ship together with their former jailers and torturers. The intention was clear. Being confined in close quarters on the same ship, it was supposed that the Junta’s political opponents and their embarrassing liabilities would massacre each other en route. It indicates how serious the generals were about winning the conflict.

The conduct of the Argentine military in the campaign was always cowardly, Alicia tells me. On another ship, they transported 100 dogos (a hunting dog) which they sent running across a no man’s land to attack the British machine gunners. One can imagine how that ended. They otherwise sent out young boys doing national service to be killed by professional soldiers, while officers excused themselves on grounds of ill-health, sometimes shooting themselves in the foot. As for the represor ex-schoolfriend, the bastard is probably still alive somewhere. The torturers and the tortured never clashed on the ship in the intended bloodbath and none of them saw action, either, thanks to a timely surrender at Stanley. It cuts both ways. Alicia has a cat she calls Belgrano. When she tells it off, it speeds to the bedroom to pee in her shoes.

The husband of a friend of Alicia, was another represor. When she came back from Spain in 1978 and visited the family, the policeman was eager to know what was being said about Argentina in Europe. When Alicia repeated a newspaper report that spoke of several bodies washed up on the Uruguayan bank of the Río Plata, the man laughed. This was in front of his wife and children. “Well, we’re getting rid of ten thousand a year,” he said. “Do you think there’s time to bury them? We take the dead and the half-dead and the living and drop them from transport planes in the river where currents will take them out towards Africa and there’ll be no trace of them. Those few must have been dropped on the wrong side of the stream by mistake.”

Alicia’s opinion is that it was no mistake and that such news served to deter political opposition. This was in the run-up to the World Cup held in Argentina that year.

El Árbol

De la violenta madrugada

un hombre entra a su casa y el olor de sus hijos

le golpea la cara, los olvidos, la furia,

ahora cierra la puerta con doble llave

y se saca la gente, la ropa con cuidado,

apaga los gritos de la camisa

o los ojos del camarada que brillan en la cárcel

y oye cómo se mueve la ternura en la pieza,

bajo su ramas dormirá todavía una noche,

bajo su ramas yacerá cuando caiga.

Juan Gelmán

Argentina is a world of fiction and Buenos Aires its grand theatre.

Santiago de Chile

At the café, as Javier and I blather on about Nietzsche and Bob Marley, an ambulance screams by pursued closely by a police van. Bam! Bam! A smell like gunpowder and I’m so stoned that I take it for granted that an ambulance is being shot up by the police. “Cosas políticas,” we are told.

Save me from the red equalizers says the white Pope. Bring that cactus back from the photographic dinner party and let loose the flics, God has given me this new razor unit, from now on all Christs will save with closely shaven chins and other small talk we tricked the Mormons out of, now they wear Rasputin beards and bear a stoop we love the fishes in the sea but give us a snort of incense and I’ll flay your fritters, no one has a right to allot you a distinctive tartan, my grandfather had mixed salad to the rim of his pot, me encantaría la cuentita, you speak worse English than de Gaulle his name was not Nigel, cream me off some of them wriggling Wisconsin lawyers. I eat better after a can of worms, I fell to the back of the shadows of others less black than mine, there’s no forgiveness but a coming to senses and the greatest of these is Mohammed Ali he still pens better than George Harrison, then fly, mitraillez les grands culs sots and don’t spare the torsos fascistas smoking pot who go and shit in the same garden all the cats pick on we have collected the mittens of the world and put them in the hands of bad audiences, the man who put the F in Folkestone and a female woman turn in a set of truth-salteñas that gather dust on a Genevan balcony Chris Colombus’s compass is there too and so am I and so are you. Keep from dusty places and grow into your loved ones. I am all in. Throw me a blanket and take off. Mulligatawny stew.

After trekking back from Puerto Montt to Bogotá, I returned to England fevered with paratyphoid and spent a while in the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in St Pancras, to whose staff I am forever grateful.

Alicia’s opinion is that it was no mistake and that such news served to deter political opposition. This was in the run-up to the World Cup held in Argentina that year.

El Árbol

De la violenta madrugada

un hombre entra a su casa y el olor de sus hijos

le golpea la cara, los olvidos, la furia,

ahora cierra la puerta con doble llave

y se saca la gente, la ropa con cuidado,

apaga los gritos de la camisa

o los ojos del camarada que brillan en la cárcel

y oye cómo se mueve la ternura en la pieza,

bajo su ramas dormirá todavía una noche,

bajo su ramas yacerá cuando caiga.

Juan Gelmán

Argentina is a world of fiction and Buenos Aires its grand theatre.

Santiago de Chile

At the café, as Javier and I blather on about Nietzsche and Bob Marley, an ambulance screams by pursued closely by a police van. Bam! Bam! A smell like gunpowder and I’m so stoned that I take it for granted that an ambulance is being shot up by the police. “Cosas políticas,” we are told.

Save me from the red equalizers says the white Pope. Bring that cactus back from the photographic dinner party and let loose the flics, God has given me this new razor unit, from now on all Christs will save with closely shaven chins and other small talk we tricked the Mormons out of, now they wear Rasputin beards and bear a stoop we love the fishes in the sea but give us a snort of incense and I’ll flay your fritters, no one has a right to allot you a distinctive tartan, my grandfather had mixed salad to the rim of his pot, me encantaría la cuentita, you speak worse English than de Gaulle his name was not Nigel, cream me off some of them wriggling Wisconsin lawyers. I eat better after a can of worms, I fell to the back of the shadows of others less black than mine, there’s no forgiveness but a coming to senses and the greatest of these is Mohammed Ali he still pens better than George Harrison, then fly, mitraillez les grands culs sots and don’t spare the torsos fascistas smoking pot who go and shit in the same garden all the cats pick on we have collected the mittens of the world and put them in the hands of bad audiences, the man who put the F in Folkestone and a female woman turn in a set of truth-salteñas that gather dust on a Genevan balcony Chris Colombus’s compass is there too and so am I and so are you. Keep from dusty places and grow into your loved ones. I am all in. Throw me a blanket and take off. Mulligatawny stew.

After trekking back from Puerto Montt to Bogotá, I returned to England fevered with paratyphoid and spent a while in the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in St Pancras, to whose staff I am forever grateful.

A lot more happened to me than appears in this scrappy memoir, which I put together by way of thanking the universe for the good people of the Andes, for the special ones that I met, and for lifelong friends in Ian and Ron.