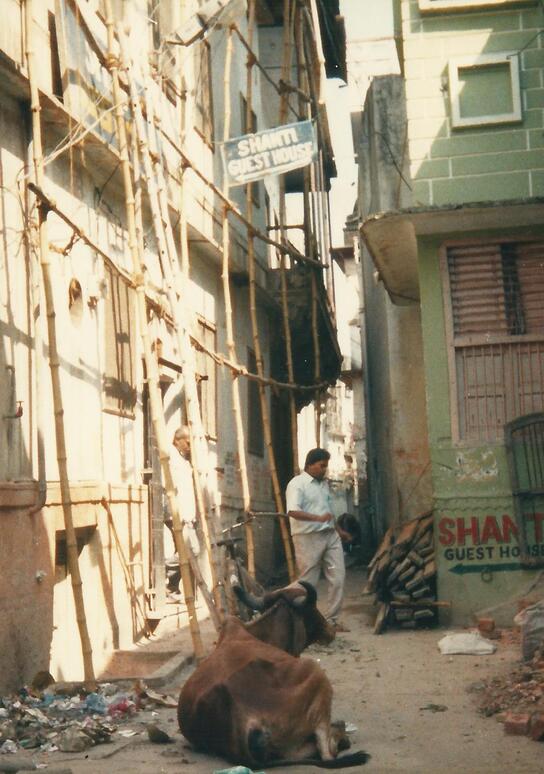

Kiran Guest House, Delhi, Oct 11th

I am agog. Wobbly on my legs but tea puts me right. Ron and his presence take the slog out of things. We have train tickets for the Taj Express to Agra.

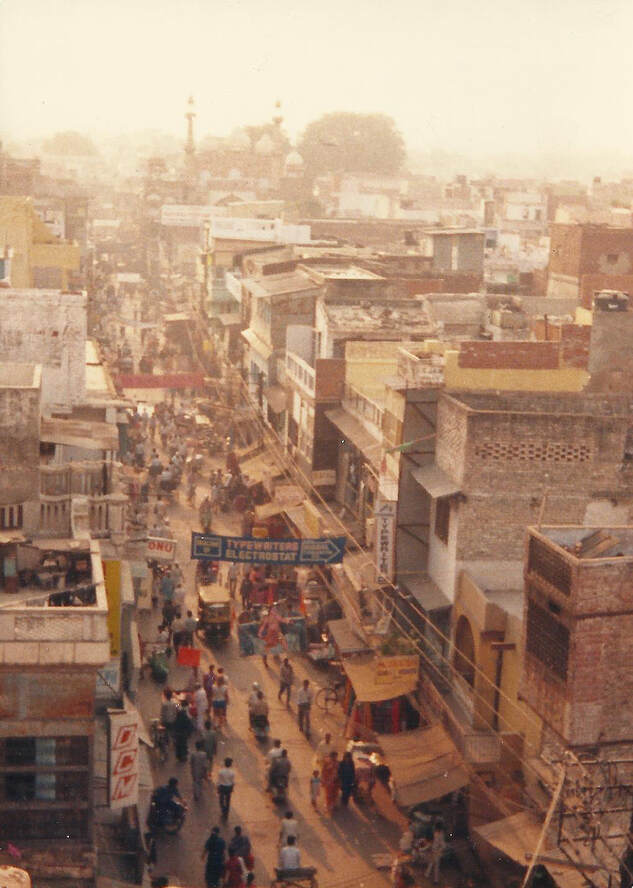

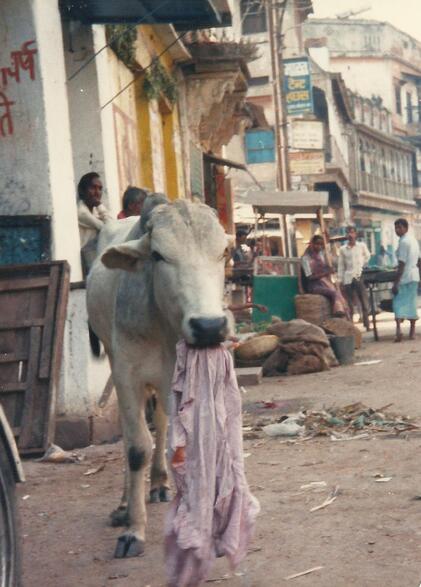

A Brahman is someone who pushes in queues. Little children are hauled off to the Little Angels Nursery School in what looks like a hangman’s cart. Cows amidst the city chaos.

I am agog. Wobbly on my legs but tea puts me right. Ron and his presence take the slog out of things. We have train tickets for the Taj Express to Agra.

A Brahman is someone who pushes in queues. Little children are hauled off to the Little Angels Nursery School in what looks like a hangman’s cart. Cows amidst the city chaos.

On the Taj Express. Witness the land. Monkeys. Dereliction and ancient crumbling.

Having left “The Hobbit” on the Bangkok leg of the Aeroflot flight, I move on to Castaneda’s “The Fire Within”: “There is nothing wrong with man’s sensuality. It’s man’s ignorance and disregard for his magical nature that is wrong.”

Agra

A camel pulling a cement mixer.

We go to the Gemini Circus at the Red Fort. After the hippo and whizzing Vespas, in rides a bear on an Enfield. She makes three circuits and exits.

“There is no law and order in India,” says Bruce. He will have his house cleared of squatters by paying a service provider 100,000 rupees.

Self-immolations of upper caste students with no future. Painted on the train: “Study well, Go to hell”.

I have my neck scraped by a razor to finish off a brutalist haircut. My real head is ghosting an inch and a half behind my visible one. Or is it the other way round?

Bruce never leaves the hotel unless he has to, in case his sitting tenants try to have him killed. A thousand rupees buys a shooting these days. The hotel owner, a Catholic from Cochin, has 25 men he can call on if need be, sitting outside his brother’s jeweller’s over the way. The Christians here are poor, few in number and generally ignored. Some of the lower caste poor are brought into the church by the offer of a weekly tin of dried milk, after which no more is done for them. Buddhists occasionally counter this by whisking people off to Nepal, where the employment situation is even grimmer.

Having left “The Hobbit” on the Bangkok leg of the Aeroflot flight, I move on to Castaneda’s “The Fire Within”: “There is nothing wrong with man’s sensuality. It’s man’s ignorance and disregard for his magical nature that is wrong.”

Agra

A camel pulling a cement mixer.

We go to the Gemini Circus at the Red Fort. After the hippo and whizzing Vespas, in rides a bear on an Enfield. She makes three circuits and exits.

“There is no law and order in India,” says Bruce. He will have his house cleared of squatters by paying a service provider 100,000 rupees.

Self-immolations of upper caste students with no future. Painted on the train: “Study well, Go to hell”.

I have my neck scraped by a razor to finish off a brutalist haircut. My real head is ghosting an inch and a half behind my visible one. Or is it the other way round?

Bruce never leaves the hotel unless he has to, in case his sitting tenants try to have him killed. A thousand rupees buys a shooting these days. The hotel owner, a Catholic from Cochin, has 25 men he can call on if need be, sitting outside his brother’s jeweller’s over the way. The Christians here are poor, few in number and generally ignored. Some of the lower caste poor are brought into the church by the offer of a weekly tin of dried milk, after which no more is done for them. Buddhists occasionally counter this by whisking people off to Nepal, where the employment situation is even grimmer.

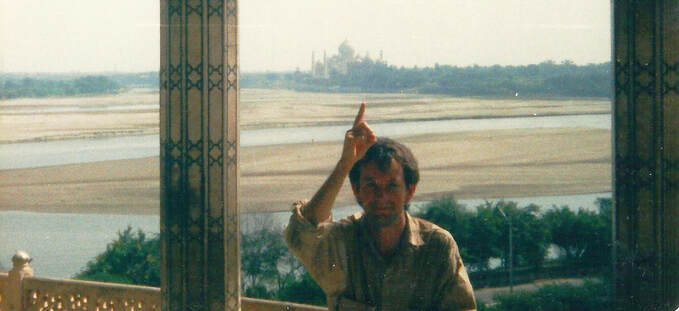

We stand shoeless at the Taj Mahal waiting for Ian to appear. The day is nearly gone. Ian is the last of we three to fly out to India and today—outside the Taj Mahal at sundown—is set as our rendezvous. Bats fly across the fading day. The warm marble cools. We wait until dark, but Ian is a no-show. Ron wants to use our pre-paid train tickets and make straight for Varanasi, and I’m easy, so we grab our bags at the hotel and get a taxi to Agra railway station. Ron is nothing if not a man who knows his rights, and I’m learning to defend myself against the mad onslaught that is India, so that when we climb on board the Varanasi train and our seats are taken, first we argue with the occupants, who refuse to budge, and then we storm off to the Station Manager’s office and demand that he take action. After patiently hearing us out, he inspects our tickets and says: “These are for tomorrow.” Which is when the penny drops. Ron had bought train tickets for the evening of Ian’s arrival: but that date is tomorrow. It is back to the Paradise Guest House for us.

The following afternoon, we are back at the Taj Mahal and as the sun sets again, there is Ian! He already has tales to tell of being ripped off by a holy man. If those train seats yesterday had been empty, or if we’d stayed on and sat on our bags to Varanasi, we’d have missed him, and our journey together wouldn’t be happening.

The Golbagh Palace’s former hunting lodge is sliding into dilapidation and we are staying there. Our suite of rooms has a writing bureau and a divan but the shower merely dribbles. The manager has no pen. The residence stands on its dignity, the grand proportion of its rooms and the solemn, weighty silence of history. The lounge, mounted with tiger heads, grave portraits and huge mirrors, has a vast hearth and armchairs that must date to the earliest days of the Raj. We cross a hall sporting more sombre oil paintings and tiger heads (I make it fourteen so far) and a fountain that doesn’t work to a dark dining room. Everywhere is delightfully shadowy, in fact. Observed by leopard heads this time, we are served on an old dinner service and informed that the Mararajah of Bharatpur still lives at the wondrous redstone palace, but at the age of 74 does not receive guests. As there are dogs and armed guards to enforce his wish, we shan’t press our attentions. In the grounds, until the last second, I am too distracted by peacocks to see that I am walking a couple of feet away from a sleeping tiger on the other side of a flimsy chain fence.

Over Defence Forces rum, Bruce says that Indira Gandhi had her son Sanjay killed because he was usurping her authority. He was having pavements crowded with the poor bulldozed so that they would go back to their villages, to the great satisfaction of shopkeepers. This kind of direct authoritarian rule is what most Indians approve of, he claimed. “Many older Indians mean it when they say: ‘Things were better under the British.’”

I dream of machine-gunning in a south coast English seaside town, a princess having sex with the old chief minister, a delicatessen selling a fish called “whale boy” and of desiring to have Les Dawson knighted and made Foreign Secretary.

The Golbagh Palace’s former hunting lodge is sliding into dilapidation and we are staying there. Our suite of rooms has a writing bureau and a divan but the shower merely dribbles. The manager has no pen. The residence stands on its dignity, the grand proportion of its rooms and the solemn, weighty silence of history. The lounge, mounted with tiger heads, grave portraits and huge mirrors, has a vast hearth and armchairs that must date to the earliest days of the Raj. We cross a hall sporting more sombre oil paintings and tiger heads (I make it fourteen so far) and a fountain that doesn’t work to a dark dining room. Everywhere is delightfully shadowy, in fact. Observed by leopard heads this time, we are served on an old dinner service and informed that the Mararajah of Bharatpur still lives at the wondrous redstone palace, but at the age of 74 does not receive guests. As there are dogs and armed guards to enforce his wish, we shan’t press our attentions. In the grounds, until the last second, I am too distracted by peacocks to see that I am walking a couple of feet away from a sleeping tiger on the other side of a flimsy chain fence.

Over Defence Forces rum, Bruce says that Indira Gandhi had her son Sanjay killed because he was usurping her authority. He was having pavements crowded with the poor bulldozed so that they would go back to their villages, to the great satisfaction of shopkeepers. This kind of direct authoritarian rule is what most Indians approve of, he claimed. “Many older Indians mean it when they say: ‘Things were better under the British.’”

I dream of machine-gunning in a south coast English seaside town, a princess having sex with the old chief minister, a delicatessen selling a fish called “whale boy” and of desiring to have Les Dawson knighted and made Foreign Secretary.

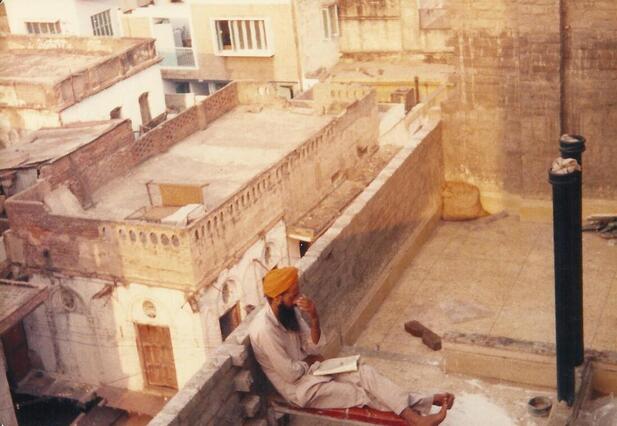

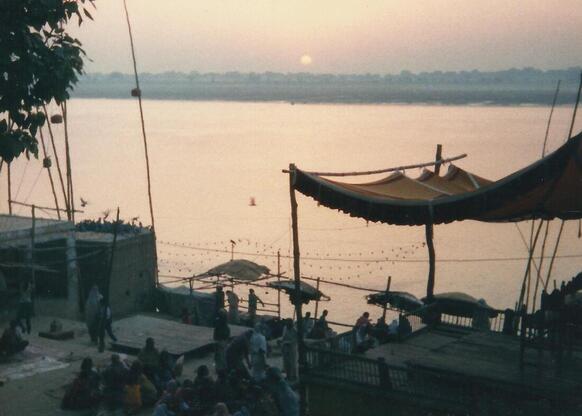

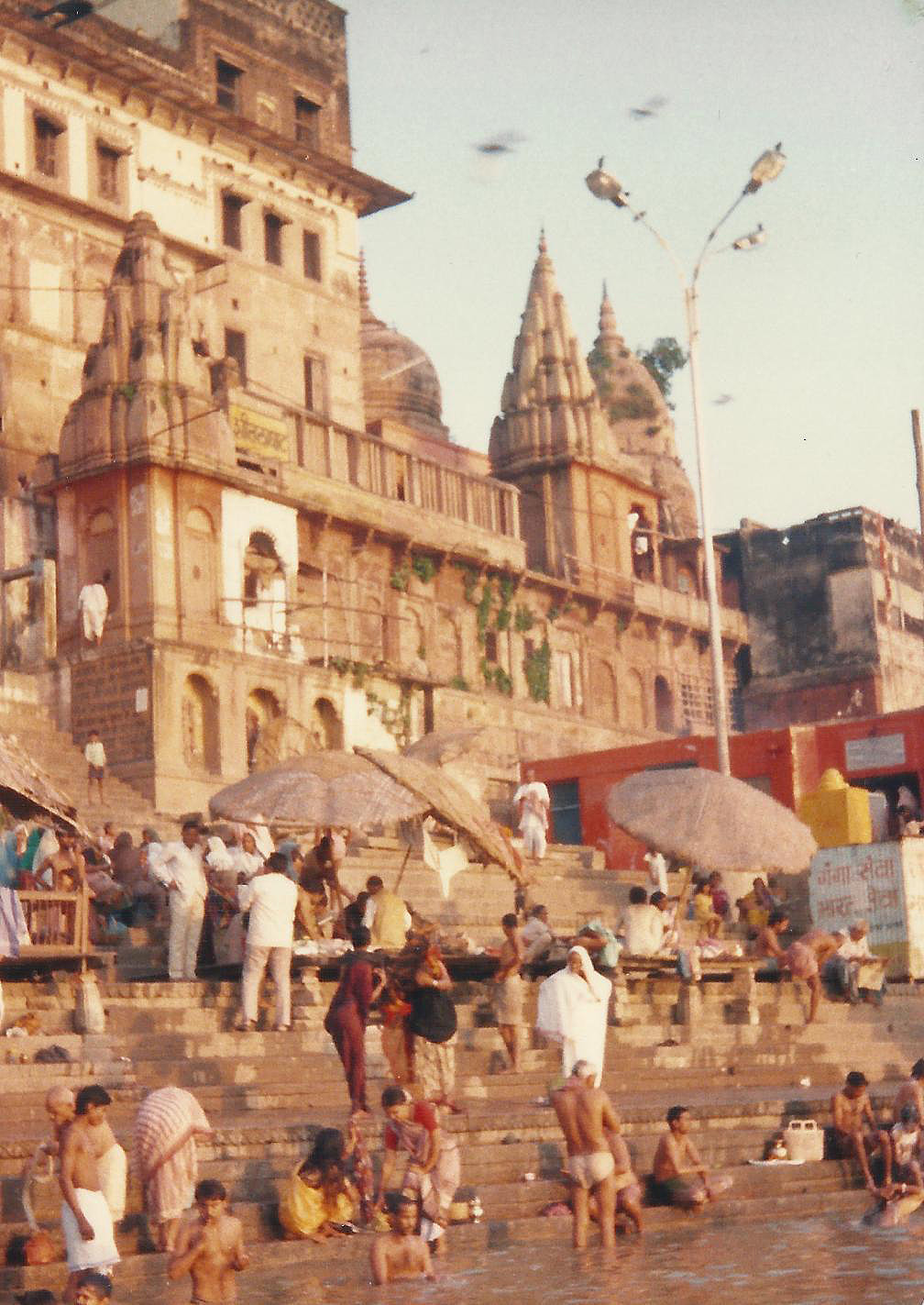

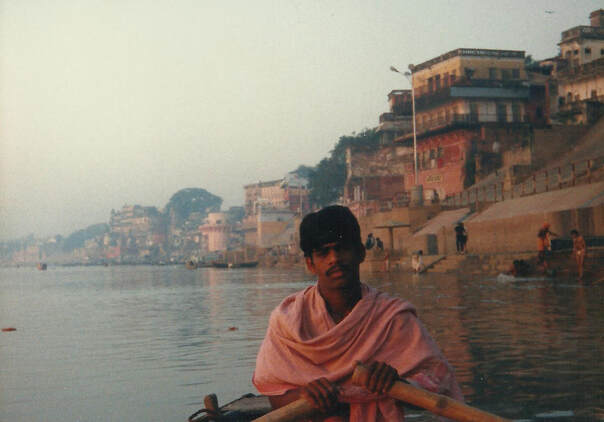

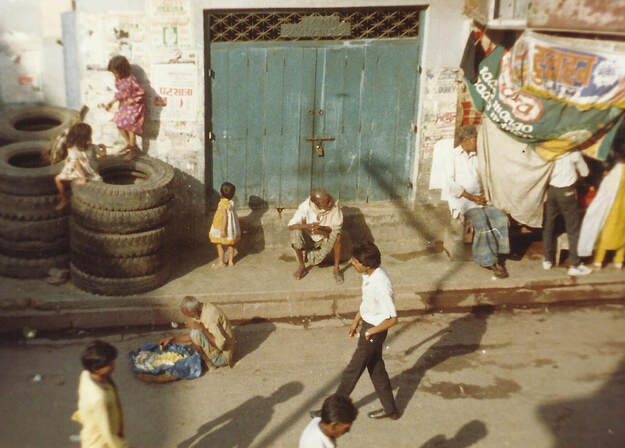

Varanasi

I am failing to focus on this alternate reality. In other words, to all intents and purposes, I continue to fucked out of my head by this place. I really don’t know what’s going on. Constant barrage of an alien world. Ears, eyes, nose, tongue, skin. Nick said, you stay long enough here, you start speaking pidgin English to everybody.

While I sit on my bed and sort some things out, a young man stands in the doorway and watches. My challenging look is clearly nothing of the kind and has no effect, so I go and gently close the door in his face. When I open it five minutes later, he is still there, and carries on staring. There is no concept of personal space in India. People will come right up to you and just stare in your face, as if you were an imported exhibit, there only for their curiosity.

Down at the Ghat, a Hindu epic is being enacted. As long as a Hindi film? Oh no, it goes on for hours every night and is scheduled to be completed in a month.

I am failing to focus on this alternate reality. In other words, to all intents and purposes, I continue to fucked out of my head by this place. I really don’t know what’s going on. Constant barrage of an alien world. Ears, eyes, nose, tongue, skin. Nick said, you stay long enough here, you start speaking pidgin English to everybody.

While I sit on my bed and sort some things out, a young man stands in the doorway and watches. My challenging look is clearly nothing of the kind and has no effect, so I go and gently close the door in his face. When I open it five minutes later, he is still there, and carries on staring. There is no concept of personal space in India. People will come right up to you and just stare in your face, as if you were an imported exhibit, there only for their curiosity.

Down at the Ghat, a Hindu epic is being enacted. As long as a Hindi film? Oh no, it goes on for hours every night and is scheduled to be completed in a month.

|

Two mice. One runs in under my bedroom door, which I subsequently block with my old Reeboks. The other is on the barber’s shelf where I am having a second haircut already. In the mirror I watch a woman’s corpse is being carried by to the everyday chant of the dead. Cows, bullocks, dogs, and the very old who have come here to die. Christ, the endless stream of ancient creatures that dropped from the train at Agra when the ticket inspector chucked them off! It awes me still. Then I got drenched by a flood of water from the carriage roof, a detail that went unnoticed in the unfathomable experience of Indian anything.

My feet itch and there is ingrained dirt in me. Indians live on grease and sugar, marvels Jackie. Insects. Insects. Four metres of dusky green silk. Insects. Two October the eighteenths. Ghost stories. Alleys teeming with 830 million people can’t all be wrong. |

Prehistoric man in a white lab coat in some Berlin university lab, experimenting on uses to which other people’s skull, skin, ears, fat could be put. “Ja, Herr Doktor. A new use for the big toe: see, one can adapt the joint for a quick-acting cigarette lighter. Now if only Herr Krupp can produce it in quantity!”

Here they refill non-disposable lighters with fly-spray.

Come see my brother’s beggar factory.

There are shops that don’t sell anything. Or they have five things. A bar of soap, a packet of cigarettes, and three potatoes.

Here they refill non-disposable lighters with fly-spray.

Come see my brother’s beggar factory.

There are shops that don’t sell anything. Or they have five things. A bar of soap, a packet of cigarettes, and three potatoes.

|

The cows are Varanasi’s refuse system. Your average cow will get through a couple of cardboard boxes in as many minutes. I stopped to stand and watch a cow chew and swallow an entire shirt. Nick saw one nuzzle past vegetable peelings, and orange and banana peel, to get at a plastic bag.

Ian and I walk through a long, narrow market dedicated solely to plastic and end up a café on a crossroads. We order bhang lassi. “Medium or strong?” “Medium.” The traffic policeman comes in on a break from point duty in the middle of the crossroads and orders a bhang lassi as well. We only just make it through the plastic market and back to the guest house before it comes on strong. I play cards in an attempt to focus and maintain a type of sanity. It doesn’t work so well. Ian, in bed a foetal position, has universes coming at him. At one point he is in a console and presented with a choice of buttons to press. One is marked: creation. I wish him a good night. “I’ll see you when you arise a new man, phoenix-like from the ashes.” “The way to handle them,” I said, “is to act even weirder than them. They respect that.” |

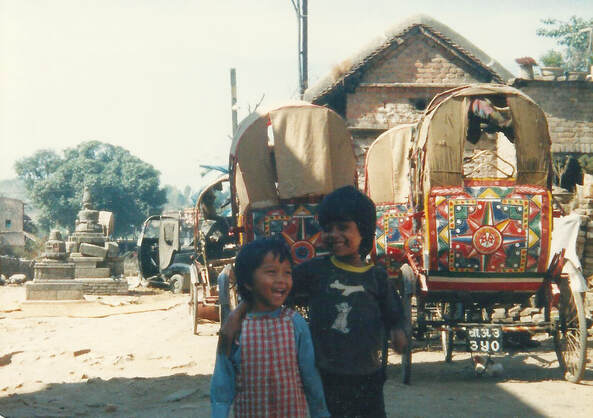

Nepal

Kathmandu

The tailor wears mourning white for his dead mother. He tells us that the police killed 500 people in April, including two of his friends and an Englishman taking photographs. The king owns an entire village in Switzerland, he says. Tomorrow is the queen’s birthday. “She is a prostitute,” our tailor says. On Friday King Birendra is to promulgate the Constitution. Today there is a popular demonstration and the shops have shut. Near the Royal Palace, behind a wooden grille, is a giant white Bhairab, fierce and hungry. I get another red dot on my forehead from the sadhu. Ron says he won’t play me at parchese with this one on.

The sea is calm and strong

The good sailor prospers

Vigilance of the sun and moon

The armies disbanded

The tailor wears mourning white for his dead mother. He tells us that the police killed 500 people in April, including two of his friends and an Englishman taking photographs. The king owns an entire village in Switzerland, he says. Tomorrow is the queen’s birthday. “She is a prostitute,” our tailor says. On Friday King Birendra is to promulgate the Constitution. Today there is a popular demonstration and the shops have shut. Near the Royal Palace, behind a wooden grille, is a giant white Bhairab, fierce and hungry. I get another red dot on my forehead from the sadhu. Ron says he won’t play me at parchese with this one on.

The sea is calm and strong

The good sailor prospers

Vigilance of the sun and moon

The armies disbanded

Pokhara

At the Butterfly Lodge, Govinda is stringing lights up for Constitution Day, when: “Nobody works,” he assures me. The first thing the Nepalese will do is get drunk. He shows me his marijuana tree, which is very, very big. “Look, here, I put up branch to dry for later. You come, just take.” ”What can I say?” “Nothing. Gift from Shiva.” He says just what the Indian taxi driver had told me: “Shiva: 24-hour smoking god” and waggled his head.

Swiss George wants Switzerland to be more like Nepal. The Nepalese want Nepal to be more like Switzerland.

Govinda and his wife Krishna sit in the dark by a large pot. They are brewing up a special tea for their cow. They do this every night and “Milk is sweet in the morning.”

A dog we call Gropius decides to be our guide all the way up Sarangot. All the mountain people try to sell you weed. It appears to be their sole industry. One man shows me his tree. “Six metres,” he said. Both proud and very drunk, he pulled on it so that it bent right over.

Words don’t matter so much here.

“The Movement” in April lasted 49 days. One photograph shows a street in Kathmandu full of shoes. The typically loose-fitting footwear have been left behind by a running crowd. Some people have fallen and the backs of their heads blown off at point blank range. People attacking a statue of King Birendra were mown down. In Pokhara a major government building was burned to the ground. These days, Communist flags fly here and there in the rural town.

“No worry, no chicken curry,” says Govinda.

At the Butterfly Lodge, Govinda is stringing lights up for Constitution Day, when: “Nobody works,” he assures me. The first thing the Nepalese will do is get drunk. He shows me his marijuana tree, which is very, very big. “Look, here, I put up branch to dry for later. You come, just take.” ”What can I say?” “Nothing. Gift from Shiva.” He says just what the Indian taxi driver had told me: “Shiva: 24-hour smoking god” and waggled his head.

Swiss George wants Switzerland to be more like Nepal. The Nepalese want Nepal to be more like Switzerland.

Govinda and his wife Krishna sit in the dark by a large pot. They are brewing up a special tea for their cow. They do this every night and “Milk is sweet in the morning.”

A dog we call Gropius decides to be our guide all the way up Sarangot. All the mountain people try to sell you weed. It appears to be their sole industry. One man shows me his tree. “Six metres,” he said. Both proud and very drunk, he pulled on it so that it bent right over.

Words don’t matter so much here.

“The Movement” in April lasted 49 days. One photograph shows a street in Kathmandu full of shoes. The typically loose-fitting footwear have been left behind by a running crowd. Some people have fallen and the backs of their heads blown off at point blank range. People attacking a statue of King Birendra were mown down. In Pokhara a major government building was burned to the ground. These days, Communist flags fly here and there in the rural town.

“No worry, no chicken curry,” says Govinda.

|

Kathmandu

From the room Ian and I share at Hotel Sugar, I can see the pagoda of the old palace that we climbed. It has small windows that look out to the mountains and one peak is particularly prominent. “What’s that one called?” I wondered out loud. “Those,” returned an American voice not unlike W.C. Fields, who then paused for reverential effect. “Are the Himalayas.” “Oh, right. Thanks,” said I. In the growing dark, Ron and I wait for Ian to return from Swayambunath. It’s very cold yet Ron is only wearing a shirt, just like the other evening at the casino. Over a chai, he tells me that he is able to bring in from the surface sufficient energy to maintain an inner heat that keeps his whole body warm, through meditation and practising attention to the present. I remember how he once said: “I let people see as much of me as I want them to see.” |

India

Calcutta

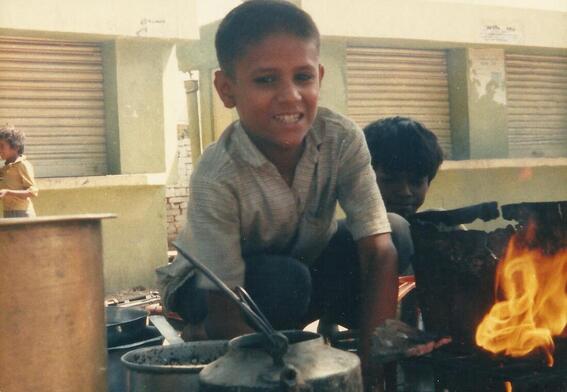

The boy who put his head in a hole. In the busy sidewalk outside a luxury hotel, where it is blisteringly hot, a small boy had scooped out a hole just big enough to insert his head. This is his gambit: to hope that rich westerners will notice his desperate ploy and suffering and leave him a few coins. I will hear of parents mutilating children to make them better prospects as beggars, but this is the worst thing I will see.

The boy who put his head in a hole. In the busy sidewalk outside a luxury hotel, where it is blisteringly hot, a small boy had scooped out a hole just big enough to insert his head. This is his gambit: to hope that rich westerners will notice his desperate ploy and suffering and leave him a few coins. I will hear of parents mutilating children to make them better prospects as beggars, but this is the worst thing I will see.

Nov 24th, Races Day

Down Collin St in sandal stroll of move and turn, go and feint, onto pavement past dog, halt for macheted green coconut water, smells, piles of tyres, bicycles and bells, loads on man-pulled carts, a slow burn rope for lighting cigarettes, in the continuum of movement, who makes the music? Children, beggars deformed and not, rocking rickshaw wheels, a clonking wooden bell, sun, warmth in shadow, dirt in the light, surfacing dirt, dirt marries all things, rest and turn the day, rest and heated volume of knotting traffic, soap, sweets, chai, a goatskin filling with pumped water, three children almost begin to play cricket and talking, conversing, dealing, advice and filling in, cooperation and hard work; fruit salad, pomegranates and mandarins, a watch repairer and paper printed by hand being loaded onto the sunbright red seat of a rickshaw, its puller not so much waiting as being there in his temporary space, hearing not listening, a motorbike horn high engine clapping, my towel dries, broken street with its corners, at one end the shop serves hot sweet milk coffee in a china cup and saucer, golob jomon, calagan, fudgy burfi. Ambassadors, idle ricksahws, shoeshiners knock their boxes at teh state of your dusty sandals, yet the filth sits lightly upon you and them and the black-an-yellow taxi has his fare and you jink past plastic toys and have come to expect the church steeple beyond the crumbling vegetation-sprouting brick and concrete soft hardness that is Caluctta, warm and hot and hugely human and happening and learning what cannot be understood and skin disease holds hands with the gold seller’s scales behind his bars and dance all three in a ring with Vishnu in a single garland of white flowers, goats’ heads and white uniformed traffic cops, grit fumes, double-deckers thumped onto the back of truck chassis, the unseen slums, ten paise in dark eyes, the feel of aniseed in the teeth after breakfast at the Khaka, Sikh uprightness opposite a bust of Indira, onion omelette, butter toast and a good glass of chai leads on to day and the reasonableness of uncertainty, up starts the music again, the lull none meant or realized was then, and now the fan spins on its axis, a line receding through concrete and head colds into a glaze o sky where it stops and is one amongst many, alone, as each is alone in a city, we do nothing and like any dog are not suffered to be separated from the company of these, the poor and only the poor give in measure and without thought, growing merit from being alive, knowing and not knowing, it is very little and it will be little more.

Down Collin St in sandal stroll of move and turn, go and feint, onto pavement past dog, halt for macheted green coconut water, smells, piles of tyres, bicycles and bells, loads on man-pulled carts, a slow burn rope for lighting cigarettes, in the continuum of movement, who makes the music? Children, beggars deformed and not, rocking rickshaw wheels, a clonking wooden bell, sun, warmth in shadow, dirt in the light, surfacing dirt, dirt marries all things, rest and turn the day, rest and heated volume of knotting traffic, soap, sweets, chai, a goatskin filling with pumped water, three children almost begin to play cricket and talking, conversing, dealing, advice and filling in, cooperation and hard work; fruit salad, pomegranates and mandarins, a watch repairer and paper printed by hand being loaded onto the sunbright red seat of a rickshaw, its puller not so much waiting as being there in his temporary space, hearing not listening, a motorbike horn high engine clapping, my towel dries, broken street with its corners, at one end the shop serves hot sweet milk coffee in a china cup and saucer, golob jomon, calagan, fudgy burfi. Ambassadors, idle ricksahws, shoeshiners knock their boxes at teh state of your dusty sandals, yet the filth sits lightly upon you and them and the black-an-yellow taxi has his fare and you jink past plastic toys and have come to expect the church steeple beyond the crumbling vegetation-sprouting brick and concrete soft hardness that is Caluctta, warm and hot and hugely human and happening and learning what cannot be understood and skin disease holds hands with the gold seller’s scales behind his bars and dance all three in a ring with Vishnu in a single garland of white flowers, goats’ heads and white uniformed traffic cops, grit fumes, double-deckers thumped onto the back of truck chassis, the unseen slums, ten paise in dark eyes, the feel of aniseed in the teeth after breakfast at the Khaka, Sikh uprightness opposite a bust of Indira, onion omelette, butter toast and a good glass of chai leads on to day and the reasonableness of uncertainty, up starts the music again, the lull none meant or realized was then, and now the fan spins on its axis, a line receding through concrete and head colds into a glaze o sky where it stops and is one amongst many, alone, as each is alone in a city, we do nothing and like any dog are not suffered to be separated from the company of these, the poor and only the poor give in measure and without thought, growing merit from being alive, knowing and not knowing, it is very little and it will be little more.

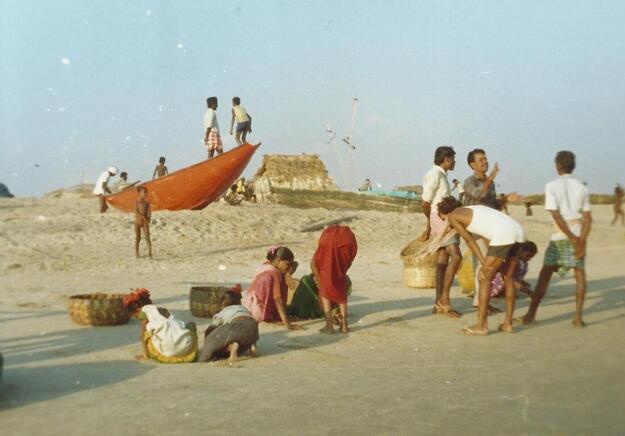

Puri

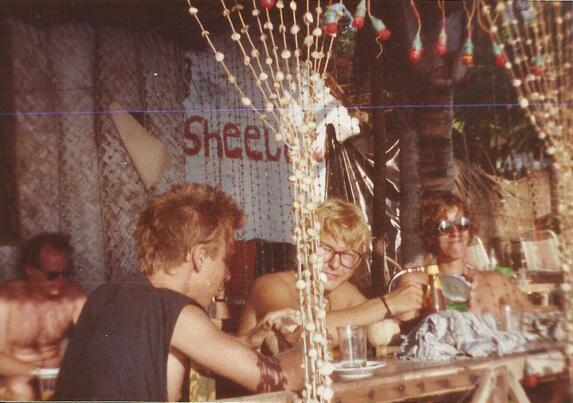

Straw huts and boats of two halves lashed together. locals’ cinema shack on the beach and their delight in martial arts mayhem. Travellers from Brighton teach us a new card game: “Shithead”. There is no skill involved, just the luck of the cards. Ian loses the first two rounds, is duly called out, and properly piqued. “I came five thousand miles to be called a shithead. No one, not even my enemies would do that. Dickhead, or prick, or cunt... but shithead.” I fail to comfort him. “You didn’t lose anything. Nothing is taken away from you.” “But people call you a shithead.” “No. People don’t get to call you a shithead. They don’t call you anything. You just are a shithead.”

And thus we learn a Buddhist card game.

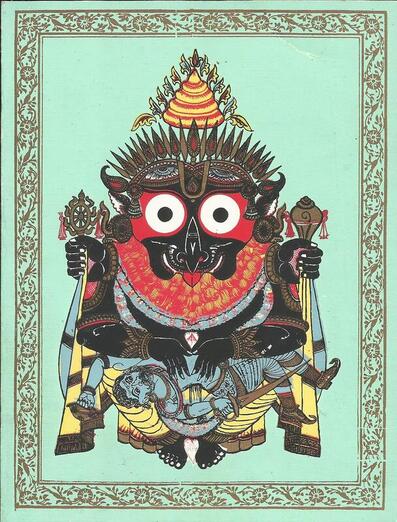

Lost to a maze of introspection. All this and the sun, sea, sky, sea air and peacefulness, laughs playing in the waves. While we’re down on the ocean front talking and playing football and splashing about, people are in the shrine further up the beach paying to images of Jagganath, his brother and his sister. This one of the four holiest cities in India. If you’ve got the Lord of the Universe living in you r town, that makes it pretty holy. He holds us in the palm of his hand. His temple is immense. At its apex, the wheel: Vishnu preserves the entire universe, creates eternally the universe, the wheel turns and is still, Shiva drums into life and burns life, but Vishnu holds life in his palm whether it is physically manifested in the form of frogs and lice and men or not, for him/her there is no before or during or after, he not subject to time, nothing can be taken away from Vishnu, nothing can be given to Vishnu.

We go night-swimming, bodysurfing by the full moon. Massive black waves, silver and white, of tremendous power. Walloped by force and going with the breaking all the way through to the foam!

Straw huts and boats of two halves lashed together. locals’ cinema shack on the beach and their delight in martial arts mayhem. Travellers from Brighton teach us a new card game: “Shithead”. There is no skill involved, just the luck of the cards. Ian loses the first two rounds, is duly called out, and properly piqued. “I came five thousand miles to be called a shithead. No one, not even my enemies would do that. Dickhead, or prick, or cunt... but shithead.” I fail to comfort him. “You didn’t lose anything. Nothing is taken away from you.” “But people call you a shithead.” “No. People don’t get to call you a shithead. They don’t call you anything. You just are a shithead.”

And thus we learn a Buddhist card game.

Lost to a maze of introspection. All this and the sun, sea, sky, sea air and peacefulness, laughs playing in the waves. While we’re down on the ocean front talking and playing football and splashing about, people are in the shrine further up the beach paying to images of Jagganath, his brother and his sister. This one of the four holiest cities in India. If you’ve got the Lord of the Universe living in you r town, that makes it pretty holy. He holds us in the palm of his hand. His temple is immense. At its apex, the wheel: Vishnu preserves the entire universe, creates eternally the universe, the wheel turns and is still, Shiva drums into life and burns life, but Vishnu holds life in his palm whether it is physically manifested in the form of frogs and lice and men or not, for him/her there is no before or during or after, he not subject to time, nothing can be taken away from Vishnu, nothing can be given to Vishnu.

We go night-swimming, bodysurfing by the full moon. Massive black waves, silver and white, of tremendous power. Walloped by force and going with the breaking all the way through to the foam!

Orissa by moonlight from the train, fields, villages, farms, palms. My towel and cut-off jeans hanging up to dry all the way to Madras Central, incense burning, a round of peanuts, an all-party reading session, and velocity. We speed south at something over 80 mph. I go to the open door to see the world hurrying by. When I come back in, Ron points out: “You just lost your bed.” So it goes in India.

Madras

In his haunted Albion House, Bruce lacks certain items that he needs to conjure up and make a pact with the Devil, such as a hazel twig and certain perfumes that must be cooked up.“If I could, I would do it tomorrow.” His whole family believes in ghosts, having seen them. To stay with the enchantment, he puts on a bad recording of a bad movie: “Ghosts”. There is shadowy movement in the dark screen, while above it on the mantelpiece lights burn, green and red, before an image of the Sacred Heart – Natalie is Catholic – and we sit in the warm air that laps in through the open door, a curtain swaying restfully, much as ourselves, and we stay sort-of-watching and sip rum with this hospitable couple.

Madras has two populations. One by day, another by night. At night, it consists almost entirely of police, who then sleep during the daytime. We are stopped four times on the way back to our hotel.

At an Anglo-Indian first communion party, the girls in dark pink jive and drink a sugary red vinegar.

In his haunted Albion House, Bruce lacks certain items that he needs to conjure up and make a pact with the Devil, such as a hazel twig and certain perfumes that must be cooked up.“If I could, I would do it tomorrow.” His whole family believes in ghosts, having seen them. To stay with the enchantment, he puts on a bad recording of a bad movie: “Ghosts”. There is shadowy movement in the dark screen, while above it on the mantelpiece lights burn, green and red, before an image of the Sacred Heart – Natalie is Catholic – and we sit in the warm air that laps in through the open door, a curtain swaying restfully, much as ourselves, and we stay sort-of-watching and sip rum with this hospitable couple.

Madras has two populations. One by day, another by night. At night, it consists almost entirely of police, who then sleep during the daytime. We are stopped four times on the way back to our hotel.

At an Anglo-Indian first communion party, the girls in dark pink jive and drink a sugary red vinegar.

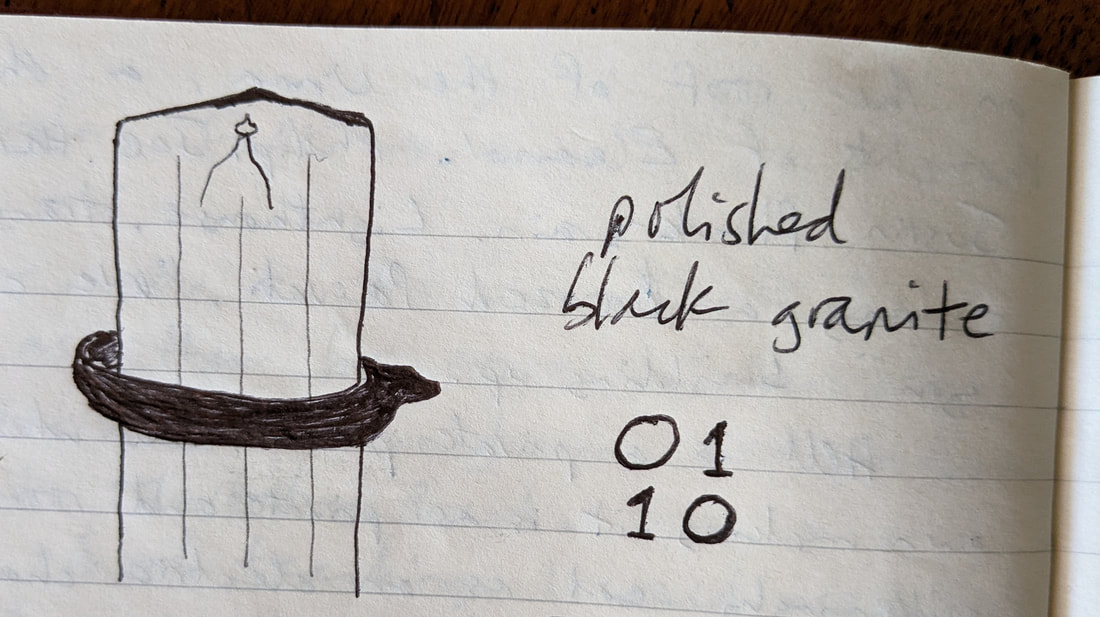

Mahabalipuram

A smooth, black granite pillar in the shore temple. Treacherous ocean. A straw hat. Vishnu reclining. Bronzed Parvati.

Louis Rosen to Pris Frauenzimmer in Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Build You”:

“I can see it’s hopeless,” I said. “Nobody can break through and reach you. And you know why? Because you want to be the way you are; you prefer it. It’s easier, it’s the easiest of all. You’re lazy, on a ghastly scale, and you’ll keep on until you’re forced to be otherwise.”

Tirukkalikundram. Five hundred steps. Two eagles.

A smooth, black granite pillar in the shore temple. Treacherous ocean. A straw hat. Vishnu reclining. Bronzed Parvati.

Louis Rosen to Pris Frauenzimmer in Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Build You”:

“I can see it’s hopeless,” I said. “Nobody can break through and reach you. And you know why? Because you want to be the way you are; you prefer it. It’s easier, it’s the easiest of all. You’re lazy, on a ghastly scale, and you’ll keep on until you’re forced to be otherwise.”

Tirukkalikundram. Five hundred steps. Two eagles.

|

We learn a Buddhist card game.

Shithead The aim of the game is play out all your cards and be left with none. Each player is dealt 9 cards: 3 to be held in the hand, 3, turned up, 3 turned down. Before play begins, each player rearranges held and upturned cards so that the upturned are the best cards (2’s, 10’s, aces & down). The player with a 3 goes first (elsewise a 4). Players must beat or match the numerical value of the card turned up next to the pack, and so on until one cannot go and must pick up the pack. A 2 played reduces the value of the pack to 2. Four cards of the same number played consecutively clears away the pack and you have another go. A 10 clears away the pack as long as it is played on a value lower than 10. And you have another go. When you play, you get rid of your low cards first. The last player left in is a shithead. This is a wonderful game. I call it Buddhist since the loser and their ego are punctilously called “shithead” by the other players. Ian does not take it well when he loses the first two games, and yet it is not down to skill, just the random luck of the draw. |

Trichy, Dec 16th

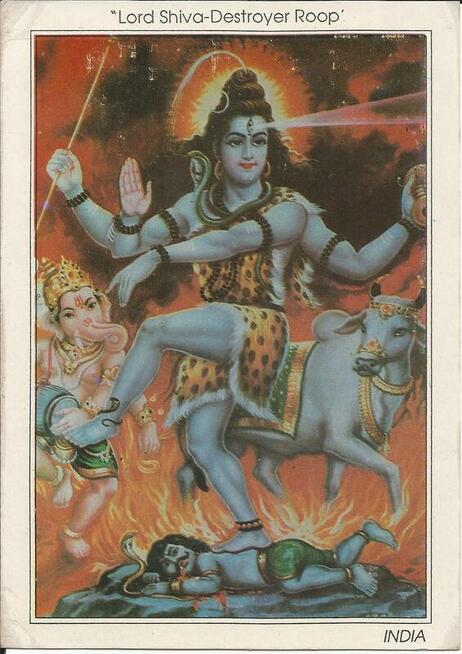

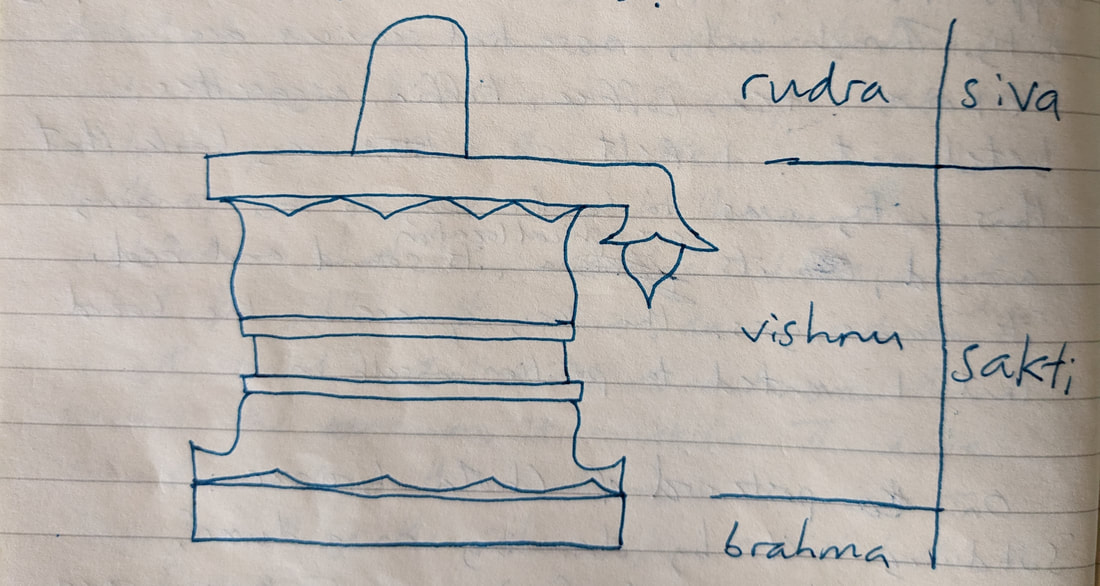

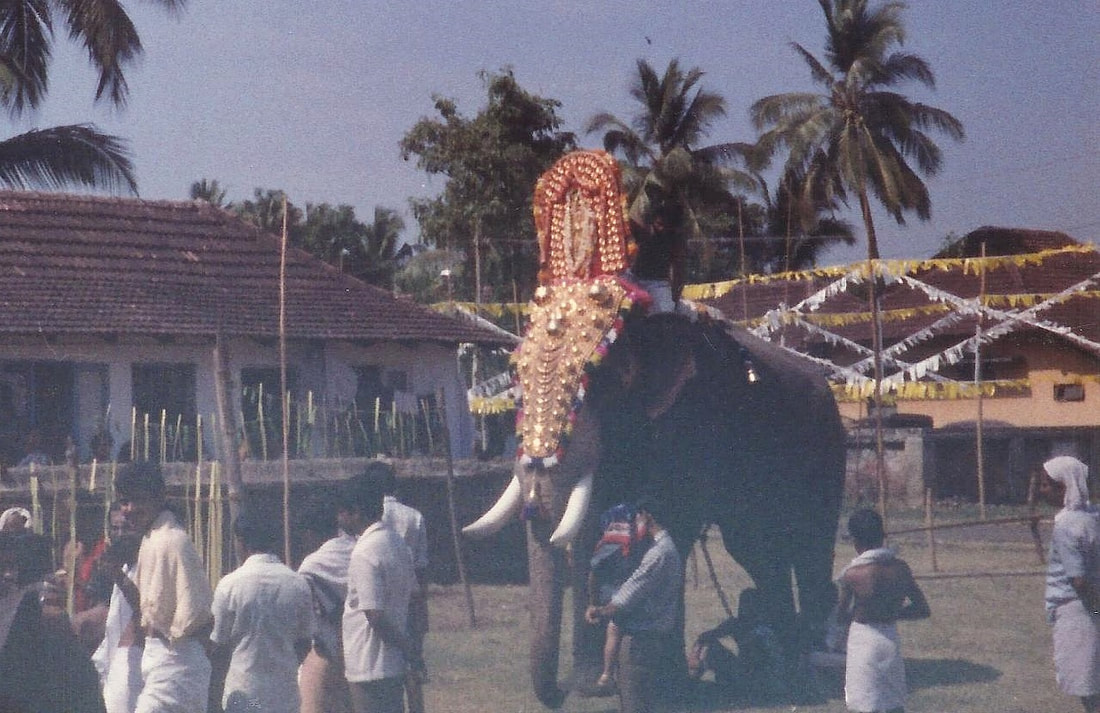

“ Just one, just one of you out of 830 million, do something silly!” I plead. Some hope. We find ourselves wrestling with our experience of India as if we might thereby stretch and pull ourselves to a new shape, a new angle to give us a fresh and profitable run at it all. At the vast complex of temples called Srirangam, one git simply wouldn’t leave us alone, pestering so tirelessly that we just sat down. Ron said: “Where is the spirituality?” I said: “Why is it all so humdrum?” In Kathmandu, certainly, we found it, and as for Varanasi...(!) But here the temple-going seems superficial and business-like. A hint of it, when a pilgrim joins hands above his head before the eternal flame. Otherwise, materialism is the worshipful paradigm. Fetishism that is kith and kin to the voodoo that Bruce affirmed was general practice within Hinduism. A re you a businessman requiring success in a deal? To Ganesh you go. A childless woman who needs a child? Kali has the power. And the many images taken thus seriously and idolized, invested with the psychic power of the thousands, must surely acquire a power and sometimes dispense it, while the spiritually real that they fleetingly represent is ignored and lost and the vulgar alone is credited. The living gods are in uniquely sensuous relationship. Ganesh is the god of the prosperity of wisdom: wisdom born of the erotic union of the black bull lingam of the cosmic dancer, Shiva, and Parvati the Beautiful, who imparts the truth of natural violence, also. Shiva, trident in hand, smokes the plant that channels world in, world out, world away in his third eye. He drums reality into existence and burns it up: this is the present and ever the present and the present is the dance, the conqueror of the demon-self. Does Nataraj point to the defeated demon? No, it is underfoot and of no more interest. He points to the other foot raised in dance. But neither does he look at this foot because attention is not on the mechanics of the body, on a body-image frozen in motion, but on the dance everlasting. Vishnu the wise, the peace beyond all activity including understanding. No time, no fear, no need: all is, nothing to be done and we were ever here. The power that keeps all things in existence knows no limit, energy as such has no measure, boundless and complete, holding all in its palm, preserving from love, the sweetness that comes forth from strength, unimaginable yet allowing itself to be known, Lord of the Universe, the peace: the peace of timeless wisdom which is our beginning and end, home, destination. All are and all is one, the incarnations of Vishnu, the consorts, the loves, the original creator who sees all (Brahman), and all mankind’s excitement and wonder, humility and discovery, her and his urgent need to express, communicate, share what has been made known.

Anyhow, precious little bloody sanctity on show in this supremely organized religion which holds each to their prescribed place with the comfort and reassurance of predictability. Individualism is ruled out, a non-starter. How I long to meet just one real character with his own ideas. As Ron said, “he would have to be very rich, or prepared to have nothing at all.” The fate of the Indian Hindu is to be a unit among countless other interchangeable units. Social togetherness is company and it is self-policing. Women are not treated much better than in Moslem countries. How dismaying for this westerner with other thoughts to experience daily the most attractive, sensual, graceful, dark-skinned women who will always be inaccessible to him! Sex I can accept (up to a point) as being ruled out, but when there can be no flirting, smiling, talking, exchanging of any kind, it saddens the spirit, it deadens and one grows plaintive. At Kodaikanal I will part company with my brave companions in search of the adventure that only travelling alone can bring on and that will also mean western women—and yet it is the Indian women I would love to know, and how!

Sign at Selva Lodge, Trichy: “Please throw the banyan leaf in the bin.”

“ Just one, just one of you out of 830 million, do something silly!” I plead. Some hope. We find ourselves wrestling with our experience of India as if we might thereby stretch and pull ourselves to a new shape, a new angle to give us a fresh and profitable run at it all. At the vast complex of temples called Srirangam, one git simply wouldn’t leave us alone, pestering so tirelessly that we just sat down. Ron said: “Where is the spirituality?” I said: “Why is it all so humdrum?” In Kathmandu, certainly, we found it, and as for Varanasi...(!) But here the temple-going seems superficial and business-like. A hint of it, when a pilgrim joins hands above his head before the eternal flame. Otherwise, materialism is the worshipful paradigm. Fetishism that is kith and kin to the voodoo that Bruce affirmed was general practice within Hinduism. A re you a businessman requiring success in a deal? To Ganesh you go. A childless woman who needs a child? Kali has the power. And the many images taken thus seriously and idolized, invested with the psychic power of the thousands, must surely acquire a power and sometimes dispense it, while the spiritually real that they fleetingly represent is ignored and lost and the vulgar alone is credited. The living gods are in uniquely sensuous relationship. Ganesh is the god of the prosperity of wisdom: wisdom born of the erotic union of the black bull lingam of the cosmic dancer, Shiva, and Parvati the Beautiful, who imparts the truth of natural violence, also. Shiva, trident in hand, smokes the plant that channels world in, world out, world away in his third eye. He drums reality into existence and burns it up: this is the present and ever the present and the present is the dance, the conqueror of the demon-self. Does Nataraj point to the defeated demon? No, it is underfoot and of no more interest. He points to the other foot raised in dance. But neither does he look at this foot because attention is not on the mechanics of the body, on a body-image frozen in motion, but on the dance everlasting. Vishnu the wise, the peace beyond all activity including understanding. No time, no fear, no need: all is, nothing to be done and we were ever here. The power that keeps all things in existence knows no limit, energy as such has no measure, boundless and complete, holding all in its palm, preserving from love, the sweetness that comes forth from strength, unimaginable yet allowing itself to be known, Lord of the Universe, the peace: the peace of timeless wisdom which is our beginning and end, home, destination. All are and all is one, the incarnations of Vishnu, the consorts, the loves, the original creator who sees all (Brahman), and all mankind’s excitement and wonder, humility and discovery, her and his urgent need to express, communicate, share what has been made known.

Anyhow, precious little bloody sanctity on show in this supremely organized religion which holds each to their prescribed place with the comfort and reassurance of predictability. Individualism is ruled out, a non-starter. How I long to meet just one real character with his own ideas. As Ron said, “he would have to be very rich, or prepared to have nothing at all.” The fate of the Indian Hindu is to be a unit among countless other interchangeable units. Social togetherness is company and it is self-policing. Women are not treated much better than in Moslem countries. How dismaying for this westerner with other thoughts to experience daily the most attractive, sensual, graceful, dark-skinned women who will always be inaccessible to him! Sex I can accept (up to a point) as being ruled out, but when there can be no flirting, smiling, talking, exchanging of any kind, it saddens the spirit, it deadens and one grows plaintive. At Kodaikanal I will part company with my brave companions in search of the adventure that only travelling alone can bring on and that will also mean western women—and yet it is the Indian women I would love to know, and how!

Sign at Selva Lodge, Trichy: “Please throw the banyan leaf in the bin.”

Dec 17th

The train pulls into Madurai four hours late and it is gone one a.m. when we walk to New College House on Town Hall Road, only to be granted three neat singles by the all-night reception. For 42/ ($2) I have a shower, dresser, mirror and hooks, writing desk and bin, all swept and spotlessly clean, and an open tea-wallah opposite to boot. A policeman tells us that Madurai is known as the no-sleeping city, although “only essential services are 24-hours: tea, coffee, tiffin, cigarettes, betel nut.”

The train pulls into Madurai four hours late and it is gone one a.m. when we walk to New College House on Town Hall Road, only to be granted three neat singles by the all-night reception. For 42/ ($2) I have a shower, dresser, mirror and hooks, writing desk and bin, all swept and spotlessly clean, and an open tea-wallah opposite to boot. A policeman tells us that Madurai is known as the no-sleeping city, although “only essential services are 24-hours: tea, coffee, tiffin, cigarettes, betel nut.”

|

Seven in the sultry evening down all the breathing aisles of beast and god. How many thousand men, women, children, Brahmans, shopkeepers is not possible to tell because they are not subject to such categories but become living pillars, sitting, standing, walking, queuing, shuffling, movement and absence, to walk upright in the eyes of the Lord is the act of worship, living is worship, unmittelbar, all the proud posturing trodden out of the world by a dancing foot, leaving consciousness of gentleness and power. Everywhere the gods are in stone. I sit on the long steps of a square pool and breathe in the heat and the prayers. Shadows and black water. There is a cloth auction, and pilgrims hurrying around the planets, which are worshipped here also. The strong faces of the women. Huge stone blocks, eighty feet high, carved in their totality.

|

Kovalum, Dec 24th

I meet Guy, a pyrotechnician, and Walt, both from Nottingham. Walt, who has locks, is so pixie-like that he reminds me of one of the Dick characters, otherwise vulnerable, who have powers of extra-sensory perception.

Dec 25th

On the beach, where someone is brewing opium tea for Christmas, I see Pete Shelley of the Buzzcocks walk by. I think I may have overdone the breakfast buckets with the three guys from Stratford but it turns out to really be him. Similarly, when I see a line of chicks wandering along under the palms dressed in fluorescent pink, green, blue and yellow that is no hallucination either. It seems the local children colour them with dye because then the crows don’t attack and eat them.

I meet Guy, a pyrotechnician, and Walt, both from Nottingham. Walt, who has locks, is so pixie-like that he reminds me of one of the Dick characters, otherwise vulnerable, who have powers of extra-sensory perception.

Dec 25th

On the beach, where someone is brewing opium tea for Christmas, I see Pete Shelley of the Buzzcocks walk by. I think I may have overdone the breakfast buckets with the three guys from Stratford but it turns out to really be him. Similarly, when I see a line of chicks wandering along under the palms dressed in fluorescent pink, green, blue and yellow that is no hallucination either. It seems the local children colour them with dye because then the crows don’t attack and eat them.

“Beach sleeping Baba,” says the mat seller.

The crows and other animals call us “the sleepers”. Always there are people lying around asleep.

The coconut and banana, sun and sun, the sand a permanent invitation to the sea. And the sea! The sea! What you can learn from the powerful one. Elsewhere she might crack your head on the sand, but here when you crash she crashes forever an inch in front of you, dancing you in her hair and when she leaves you stand up and turn to kick back in, eager to meet her in the thrilling black and bright white. Here, she soothes and salts your body, she washes you and warms you and if she is the one who clobbers you laughing, she is the also one who dances her dance for you in the breaking, the one who kisses you gently as you switch your attention to the unmoving land, fair staggering up to the beach.

The crows and other animals call us “the sleepers”. Always there are people lying around asleep.

The coconut and banana, sun and sun, the sand a permanent invitation to the sea. And the sea! The sea! What you can learn from the powerful one. Elsewhere she might crack your head on the sand, but here when you crash she crashes forever an inch in front of you, dancing you in her hair and when she leaves you stand up and turn to kick back in, eager to meet her in the thrilling black and bright white. Here, she soothes and salts your body, she washes you and warms you and if she is the one who clobbers you laughing, she is the also one who dances her dance for you in the breaking, the one who kisses you gently as you switch your attention to the unmoving land, fair staggering up to the beach.

|

Dec 29th

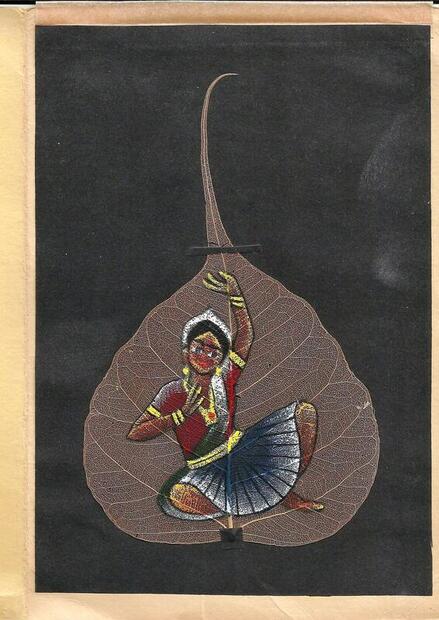

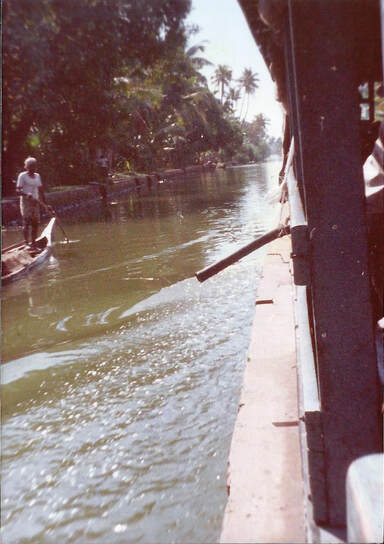

Krishna with me on an oil-painted leaf, his flute playing as I sit on the bog. On the road from Kovalum, launch from Kottayam to Alleppey and up to Ernakulum, there was something like another personality. He cares nothing for social niceties and nothing for impoliteness, either. He isn’t concerned with them: he just wanted to enjoy emerging and wanted the organizer-one (my quotidian ego-self) to let him enjoy looking at the palms against the blue sky, look out for women, flex the body he’s had no use of — and take care of this body: “It’s mine, too, you know. Give me good, decent food. I don’t mind roughing it a bit but I do mind you robbing me of adventure. Leave things to me as much as possible. And stop writing it all the fuck down. To Cochin!” We have different ways of packing. “Oh, let’s have a look,” he says. “That’s lovely: who’s that for?” He helps me out of my trousers: “You’ll never work this out. C’mon, I need a piss. Get out the way.” |

Dec 30th

Sea Gull Hotel, Fort Cochin

Sign: “Disturb no person.”

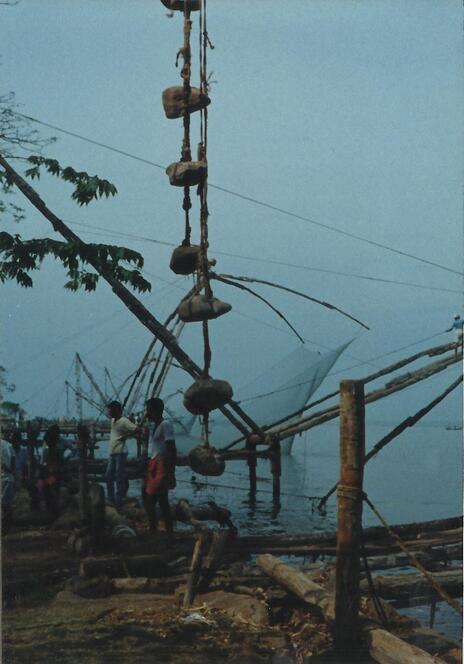

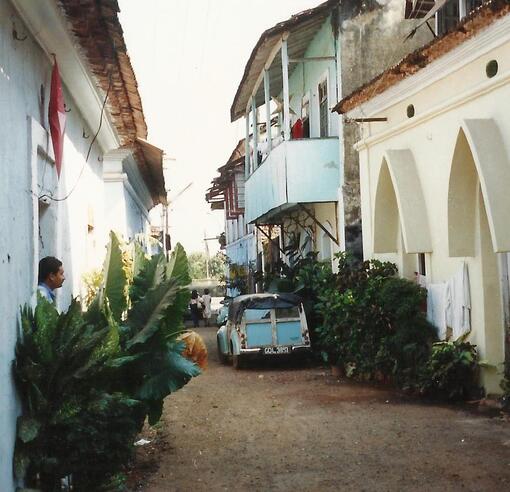

From my desk I see the ferry moving across, white and blue, to Willingdon Island. At breakfast, I watch a team raise and lower the “Chinese” fishing nets four times and catch not a thing.

Sea Gull Hotel, Fort Cochin

Sign: “Disturb no person.”

From my desk I see the ferry moving across, white and blue, to Willingdon Island. At breakfast, I watch a team raise and lower the “Chinese” fishing nets four times and catch not a thing.

What I now think of as the secondary personality, being the customary consciousness of everyday life with its compulsive behaviour and anxieties, is excited and a little alarmed at the newly emerged primary personality, unsure how far to let the latter through to take its place. The primary me, the old one, the bright and firm and intense and observant one, cannot force its way into consciousness nor can it be altered or acted upon by the everyday me. It can only be let through or not. I wonder whether the “primary” is no personality whatsoever but only conceived of as such by the “secondary” which doesn’t know how to think in any other terms. What it fears is that if it lets the alert one through more and more, that itself — the everyday worrying, needing, grasping self— will be seen to be an empty figure of no more substance than a straw man, and will then be lost from consciousness, along with its hoard of treasures, its habits and characteristics, its plans and its official history, its image of itself, and become prey to a demon-personality possessing the mind and the body. For what does it/do I know of this sassy older “me”, whose tastes and talents coincide with the usual ones sometimes, and yet often not? It does not seem interested in teaching me anything at all. Its intent is solely to experience now, live now. The everyday me, the controller, the writer of these notes, is wary of its morals. A bit of a lad is an understatement.

“I am Brahman, you are Brahman, you are the truth, the truth is you,” the swami says to me. “I am the world. You must go to lonely places and think on this.”

The alert one is the traveller, the one who does. I want to demand answers of him to a veritable questionnaire of caution. Ridiculous questions like: “Are you a vegetarian? Do you steal? What’s going to happen?”

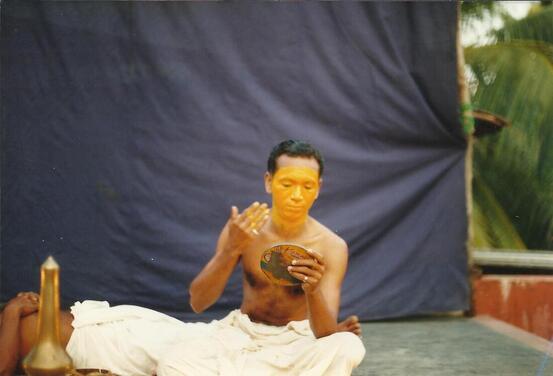

Mr Peru is taking me to a Kathakali performance. As his bicycle rickshaw rolls along, he distinguishes shops and homes: “Pakistan Moslem, Goa, Hindu, Jain, Hindu, Moslem, Moslem, Tamil.” Young women crowded behind the low doorways of Moslem houses smile, giggle, wave “Hello!” I smile and wave back.

“I am Brahman, you are Brahman, you are the truth, the truth is you,” the swami says to me. “I am the world. You must go to lonely places and think on this.”

The alert one is the traveller, the one who does. I want to demand answers of him to a veritable questionnaire of caution. Ridiculous questions like: “Are you a vegetarian? Do you steal? What’s going to happen?”

Mr Peru is taking me to a Kathakali performance. As his bicycle rickshaw rolls along, he distinguishes shops and homes: “Pakistan Moslem, Goa, Hindu, Jain, Hindu, Moslem, Moslem, Tamil.” Young women crowded behind the low doorways of Moslem houses smile, giggle, wave “Hello!” I smile and wave back.

The erotic murals of Mattancherry Palace. Krishna reclines in the forest, where all around deer and other animals are frolicking and fucking, surrounded by beautiful Gopis “in different postures”. He has hands and feet on flute and nipple and clitoris wherever his many arms can reach.

Dec 31st

The parallel personalities persist. The me I know and the one who has emerged. If “I” is the me of ordinary consciousness, the person I think I am, the person I introduce and operate with, crude, cautious and barely honest, “he” is this immediate consciousness that I don’t know what to do about. He wants to enjoy, to soak up the present as if he knows that it will be taken from him once more and soon. If he is undesirous, his attention undirected to any end, yet he has a penchant for adventure.

Women out in the afternoon sun carrying granite on their heads. At Kovalum, dozens of them cracked rocks to make them small enough for a new road. I seem to have landed a good deal in this life.

“In each of us there is another whom we do not know,” said Jung.

He does not cling to things. It is “I” who does that. He is frankly pleased to have so much. I have a notion that he no stranger to hard work, but the funny thing is, he is out to enjoy spending the money that “I” earned. So we have the miser who cannot enjoy what he has revisiting the dark horse who enjoys whatever he gets and may or may not be an utter spendthrift. C’mon, he says: let’s spend his money. It’ll drive him crazy!

Dec 31st

The parallel personalities persist. The me I know and the one who has emerged. If “I” is the me of ordinary consciousness, the person I think I am, the person I introduce and operate with, crude, cautious and barely honest, “he” is this immediate consciousness that I don’t know what to do about. He wants to enjoy, to soak up the present as if he knows that it will be taken from him once more and soon. If he is undesirous, his attention undirected to any end, yet he has a penchant for adventure.

Women out in the afternoon sun carrying granite on their heads. At Kovalum, dozens of them cracked rocks to make them small enough for a new road. I seem to have landed a good deal in this life.

“In each of us there is another whom we do not know,” said Jung.

He does not cling to things. It is “I” who does that. He is frankly pleased to have so much. I have a notion that he no stranger to hard work, but the funny thing is, he is out to enjoy spending the money that “I” earned. So we have the miser who cannot enjoy what he has revisiting the dark horse who enjoys whatever he gets and may or may not be an utter spendthrift. C’mon, he says: let’s spend his money. It’ll drive him crazy!

Rain trees in Temple Road. Heaps of leave asmoke after being swept there by old women, making so sweet a smoke that old men become children and young men, too, and I’m streaked a little melancholic.

A voice says to me, “When you see the size of your ignorance, you may want to despair. Don’t. Although; as a matter of fact, you ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Gecko tells me: “Peacock has four legs” i.e. is a god, or goddess. I really do sound like I’m going out of my mind.

A voice says to me, “When you see the size of your ignorance, you may want to despair. Don’t. Although; as a matter of fact, you ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Gecko tells me: “Peacock has four legs” i.e. is a god, or goddess. I really do sound like I’m going out of my mind.

1991

January 1991

Outside the Arsikere–Shimoga steam train, a voice in the night cries: “Here’s yer tea! Here’s yer tea!”

Outside the Arsikere–Shimoga steam train, a voice in the night cries: “Here’s yer tea! Here’s yer tea!”

Jog Falls

I lay back on a stone bench across from falls and wonder, “How can I be the universe? It’s really big.” I wait for shooting starts but don’t see any.

Waiting for a bus in a dark and cold early morning at Shimoga: where else do you find a chap out before dawn selling garlands of flowers from a basket?

I lay back on a stone bench across from falls and wonder, “How can I be the universe? It’s really big.” I wait for shooting starts but don’t see any.

Waiting for a bus in a dark and cold early morning at Shimoga: where else do you find a chap out before dawn selling garlands of flowers from a basket?

|

Karwar

Just as I start to feel miserable and lonesome, I go to buy toothpaste and the seller insists on showing me the one that I’m not buying. He opens the box, takes out the tube, takes off the cap and squeezes: “Look! Red!” he says, and shoves it up my nose. This is India at its best. Fever, shits, aching, terrible belly pains. I am almost too weak to raise a glass to my lips. There is no mineral water left in town and no proper medical facilities. What use anyway, I think, to bring a doctor who will only manage the guidebook phrase, “The patient is dying by inches.” Dinner is three crackers, one Bactrium forte, rehydration salts, paracetamol, codeine, opium and coal tablet. Two black, three white, one orange. In my Karwar sickroom I was visited by crows. I put out watermelon rind and sugary sweets for them. One said to me quite clearly: “C’mon, c’mon.” “Come on what?” I said. “It’s all very well for you to say ‘Come on’”. But when Helga got back with salt biscuits I decided to take what medication she had. I am reading “The Drifters” by James Michener. About wandering misfits abroad, would you believe. |

Hampi

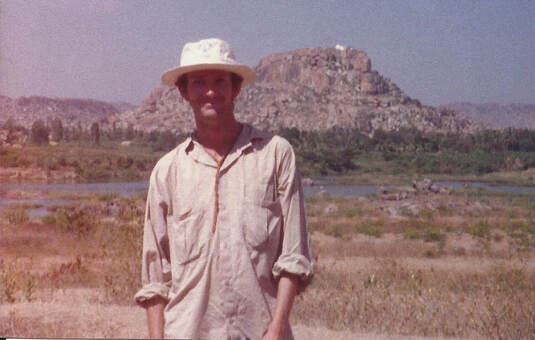

The bus rocked through a stony landscape, a valley of giant broken bones, night coming on., formidable. He surveyed the stillness of a sunset, pink and blue beyond black boulders, sucked on a Charms cigarette and blew the smoke out the bus’s rear window in a stream that said, “Give me your worst, India, your strongest, your best.”

The bus rocked through a stony landscape, a valley of giant broken bones, night coming on., formidable. He surveyed the stillness of a sunset, pink and blue beyond black boulders, sucked on a Charms cigarette and blew the smoke out the bus’s rear window in a stream that said, “Give me your worst, India, your strongest, your best.”

Typical menu: “Chicken cripes, chicken 65, chicken hens.”

On a slab of concrete beach, a man of about sixty with a thin white cotton wrap tied around his waist washes himself from a tin amphora and shouts in the sun.

On a slab of concrete beach, a man of about sixty with a thin white cotton wrap tied around his waist washes himself from a tin amphora and shouts in the sun.

Hanuman Lodge, Hampi

I ask a local sitting on a path, as stoned as me:

“Why do fish swim underwater?”

“Other side, other side,” he says and makes a pulling-down motion that means: otherwise you could shoot them down.

“The Dancing Wu Li Masters”: the physical world is not a structure built out of independently existing unanalyzable entities, but rather a web of relationships between elements whose meanings arise wholly from their relationships to the whole.

I ask a local sitting on a path, as stoned as me:

“Why do fish swim underwater?”

“Other side, other side,” he says and makes a pulling-down motion that means: otherwise you could shoot them down.

“The Dancing Wu Li Masters”: the physical world is not a structure built out of independently existing unanalyzable entities, but rather a web of relationships between elements whose meanings arise wholly from their relationships to the whole.

Calcutta

Modern Lodge, Jan 31st

Ginger chai and nice kids. When one of them fetches me a cigarette he won’t take a tip. His brother has a helium-filled balloon tied to a block of wood. Their mother coughs too much.

Try, when you are weak from the chronic shits, jumping from a truck-pulled double-decker while keeping your cheeks together.

A guy called Johnny reads out a letter in Geordie. From his brother, it begins: “Deat cunty shagpile,” and goes on to tell a moving story of human foibles and manners in that idiom. Their father is the Bishop of Durham.

The night’s brief, dramatic thunderstorm leads into a gloomy Sunday, dampening a half-light that is held in suspension from our musty dorm down to the resignation of the street. The stores are all shut. No one performs the simplest task. Only the sick pall keeps me intestinally from a great happiness. Lying on my cot in the dorm, I smell Christmas pudding. I scratch my bum with this pen and know there are less than two days to go. The curd, bananas and ayurvedic gunge that I am on cannot feed the day’s half-life. The cinema, the Book Fair, let alone the Planetarium or Zoo, are worlds away from me. I feel a kind of inverse despair. On a crow-cawing, stationary horn afternoon, mourning becomes Electrolyte, sporadic rainfall and the falling away of necessity, a slow trumpet purpling the soul. Not even a yawn stretches across the larva-day. I doubt whether the most gung-ho nerd in the Gulf can be bothered going to war this immeasurable hour: work is no more. Turn up the fan’s speed control and a stream of dirty water drops from a white-painted pipe. Natasha reluctantly accompanies Johnny to an eatery that will do a chapatti chip butty. Mariete and Helen throw us sweets.

Last images of Calcutta are shrouded in thick morning fog. Little scarlet cloaks in a school cart, a solitary humpback cow, concrete-lidded tenements of yellow dirt. When I see these and man-rickshaws becoming real out of the grey fog, I am close to tears. We hurry by the last dark gods. I exit with a bloody tikka scar across my brow, the love bite of a Scottish kiss that I gave the taxi. When I come back I intend to be older.

Modern Lodge, Jan 31st

Ginger chai and nice kids. When one of them fetches me a cigarette he won’t take a tip. His brother has a helium-filled balloon tied to a block of wood. Their mother coughs too much.

Try, when you are weak from the chronic shits, jumping from a truck-pulled double-decker while keeping your cheeks together.

A guy called Johnny reads out a letter in Geordie. From his brother, it begins: “Deat cunty shagpile,” and goes on to tell a moving story of human foibles and manners in that idiom. Their father is the Bishop of Durham.

The night’s brief, dramatic thunderstorm leads into a gloomy Sunday, dampening a half-light that is held in suspension from our musty dorm down to the resignation of the street. The stores are all shut. No one performs the simplest task. Only the sick pall keeps me intestinally from a great happiness. Lying on my cot in the dorm, I smell Christmas pudding. I scratch my bum with this pen and know there are less than two days to go. The curd, bananas and ayurvedic gunge that I am on cannot feed the day’s half-life. The cinema, the Book Fair, let alone the Planetarium or Zoo, are worlds away from me. I feel a kind of inverse despair. On a crow-cawing, stationary horn afternoon, mourning becomes Electrolyte, sporadic rainfall and the falling away of necessity, a slow trumpet purpling the soul. Not even a yawn stretches across the larva-day. I doubt whether the most gung-ho nerd in the Gulf can be bothered going to war this immeasurable hour: work is no more. Turn up the fan’s speed control and a stream of dirty water drops from a white-painted pipe. Natasha reluctantly accompanies Johnny to an eatery that will do a chapatti chip butty. Mariete and Helen throw us sweets.

Last images of Calcutta are shrouded in thick morning fog. Little scarlet cloaks in a school cart, a solitary humpback cow, concrete-lidded tenements of yellow dirt. When I see these and man-rickshaws becoming real out of the grey fog, I am close to tears. We hurry by the last dark gods. I exit with a bloody tikka scar across my brow, the love bite of a Scottish kiss that I gave the taxi. When I come back I intend to be older.