2007 Argentina

February, Rosario

I stray to a tired district where commerce struggles to be presentable and faces are lined by long working hours. Broken pavements, massive stone lions atop the Casa de España, buses launched along narrow thoroughfares, and an unidentifiable shop called “Very.” I waft along, borne by the soupy warmth.

Everything is in the balance. If it tips over too far, the crumbling façades of edifices and middle-class mores will turn inside out to show guts of unpretty poverty. A bus I was on passed by a barrio outside Buenos Aires that wanted respectability but had yet to take the determining step into it. Low, modest dwellings were placed carefully in grids of swept streets, like houses of cards in a single, glued-together layer, not quite flimsy but awaiting to be made permanent, using the existing structures as bones and scaffold. Give the men and women here some sustained work, a reason to believe in continuity, and that door would be replaced by a better one, this roof would be fixed, that father would spend some money on paint and watch his house come to look more like a home in a neighbourhood that has just gained a corner shop. When there are grounds for hope in a life in common, a person feels like a citizen. Neighbours will look each other in the eye and make a greeting. They will talk together about better provision for children, petition the council for better street lighting, go to work with a sense of purpose. Buy a new mattress, pay off a debt, think about a car and goodbye to the scooter. Swimming lessons for the girls.

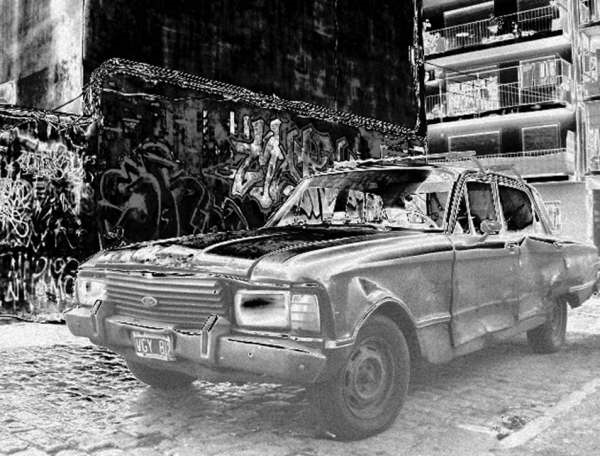

But it has only to tip the other way and this future’s eggshell is broken. Wages don’t keep up with inflation, then the new law curtailing indemnification means that reasonably well-paid workers are axed to replace them with desperate aspirants who will take less; record exports and healthy investment are publicized in the press but none of the benefits reach lower down the food chain; multiple hours worked on decreasing energy no longer make sense when the children can’t have new shoes and it’s gnocchi again. Who has work around here these days? Who stole the wheels from that car? No one repairs anything, there are fewer people in the streets at night, you keep the door firmly locked and your children note the worry in your face when the fights and the drugs start after dark. The neighbour has long forgotten her invitation to you to come round and the trash collected by the wind in the corners is less and less distinguishable from the shambles in which you are living. Even your husband no longer looks at you with the same softness as he did.

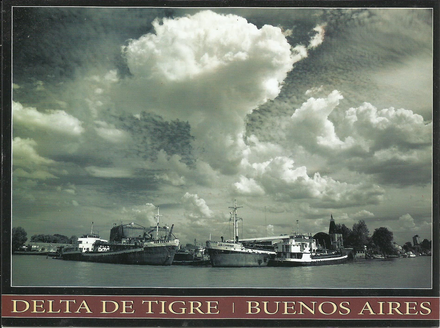

The Paraná is high, carrying a one-way traffic of matorral and sizeable vegetable chunks of delta dragged from their rooty mooring. Nati once saw a cow pass by, marooned on a tiny drifting island.

A plane flies against the current, exhorting us to go to the Superpark on Thursdays.

We crossed the bridge in driving rain, a hint of brown suggesting the swelled river. Onwards to lush, green vistas in wet eyes. Ever onward, desirous of disappearing over that hill and leaving home behind for good. The ever-receding reward of perseverance. Naïve dreams of celebrating life and liberating love. Emotional belief patterns that survive intellectual disavowal.

Today I lunched with Angel, a fat Peruvian. He has the modest ambition of opening a pet shop. His attempt to do so is proving as similarly Kafkaesque as mine to rent an apartment. Somehow, it just doesn’t happen. The money doesn’t arrive in a bank account, or a current gas bill is demanded, or a deed to guarantee the deal, or the property is let to someone else and in any case, and especially after your long trek here, Sr. Bostic is not in.

Tramp them streets in the rain and wonder.

Although K really ought to have been chasing down an electric bill (so much better than gas!) for a property belonging to someone he didn’t know and which was destined to support his rental application in exchange for a certain sum in pesos and an entitlement to marriage or soul, whichever haddeth the greater value, he splashed a path to the station, boarded a bus to a town on the border with Uruguay, and stared through the opaque windows as it rode over the bridge.

The riverside town was made up of wet houses and dogs. An unsmiling girl of twenty-five, wanting her dullness shared, had him accompany her through rain and muddy streets to the thermal baths that were the pride of the resort. Here, at least, human bodies were joined in communal rite, with warm waters spouting from a ring of gushers overhead or lapping to the rim of a round, shallow pool. Freed of clothes and social labels, old and infant, all curious shapes and sizes, stood or sat in the steamy spa and let the glass panes of the roof bear off the falling rain. The girl, thankfully, showed no sign of wishing to converse, leaving K to wallow.

The day would be darkening on his application in the city. At this hour, his inexcusable omission in leaving no contact telephone number for the agencies would be croaking loud in their ears, and changing its chameleon colour from inadvertent blue to blatant red.

I encouraged Angel to vamp up his pet shop — if he ever gets one, and there must already be one for every fifty inhabitants in Rosario – with innovative stock such as dwarf giraffes, multi-coloured seals, ostriches trained to give advice on dress sense (“Make a move for those socks and I’ll swallow them before you can you blink.”) He was more interested in the waitresses’ arses and sneaking a smoke on his herb pipe. He had been kept awake at the hostel by young Israelis on beer and cocaine (they had a guitar, can you imagine?) and I was sitting in smugly clean clothes, having moved into a temporary room all to myself in a city centre apartment down a dingy passageway, where I had been able to open my suitcase for the first time in six weeks. This is progress and I claim it. I cannot contact the woman about the dodgy guarantee, of course, and tomorrow is Saturday, but nonetheless and fair’s fair, is it not? and all the same, and it’s only dogs and children squealing down the hall, so let’s be thankful.

Then all of a sudden there’s a night out dancing bacchanalian folklore with hats and girls. Next day, the rain dries to dress the faded grandeur of façades in sunlight.

Another night and I am transported to another milonga, showered with powder and a sprig of peppermint stuck behind my ear. Ricardo sits and thinks of another bottle of beer. Cartucho has stars in his eyes. The dance between girls and boys twists and turns.

“Los argentinos, somos ladrones” insists Andrea. Which she, as a gestora, most certainly is.

22nd March

The hall, which occupied the street corner and must double as a café-restaurant by day, was high-ceilinged, capacious and dimly lit. A red light lent its hue to an empty area of seating. Along the wall of, a grand length of scarlet material was draped in languid, funereal fashion. We sat against a large window from where we could observe the milonga’s expanse, couples and friends occupying the other tables, or twisting and halting, turning and leaning, all of them, whether seated or dancing, implicated in the ritual and its mournful music. We joined Ricardo and Vila and ordered wine. Sabina sat with a half-smile in the company of men more than twice her twenty-one years and waited for it to begin.

“I don’t like this music,” Ricardo opined dutifully. Accordion sounds and light percussion played out a characteristic tango over loudspeakers. “It is alright to listen to, but not to dance.” One couple moved round the floor holding each other close, as if exchanging confidences; a short, squat man arranged himself like a ladder against a full-bodied woman, a head taller than him, and stuck an arm out high to lead her onwards; one pair of dancers moved with carefully hurried steps, as though picking their way barefoot over hot sand, while another worked slowly, introspectively in a small space, through the set pattern.

“This is like something from 1910,” Ricardo complained.

“This was written 30 years ago,” Vila said. “They just play it that way.”

“It’s not tango,” insisted Ricardo. Yet he complied unhappily when Sabina proposed a dance.

It is the tang which makes tango. The solemn obligation to accompany another in a prescribed, formal design to the chords of jaunty melancholy, in an old dance hall redolent of passionate affairs, held by its players tonight in an ambience of decorum by preference. The woman and the man, lovers or strangers, do as they must. Unsmiling and with undisclosed feeling, they will complete the moves before standing back from each other and waiting for the music to begin again.

Vila wore a black shirt tucked into dark grey slacks. Strong and well-built, looking a decade younger than his sixty-nine years, he might have been a retired cop, but he had been a tango dancer and singer. He must have seen the look on my face as I admired the scene: “Es la joda siempre. People just want to go out at night and dance.” Ricardo, El Flaco, and Sabina, little Rampilón, dipped and rose on the floor. He, tall and tragic in his thinness, balding and mustachioed, led her at courteous remove; she with finger tips placed behind his shoulder. Their silent voices sing; he calls high notes and she answers low. Leggy bird and earthbound mammal. I think he may be secretly in love with her.

“Argentinians don’t want to work. This could be a very prosperous country. But give someone the chance to make good money by coming in and working hard from 9 to 6 and they throw up their hands,” Vila gestured like someone refusing an unfair, excessive demand. Nobody’s interested: just as long as there’s a milonga to go to…”

“So how do people get by?”

“Everyone has something or other sorted out. They’re lazy, but they’re not stupid. They have an eye for the main chance. Today, I got up late, played the piano until four, went for a swim, met some friends, had a nap and came out here.” He laughed, as well he might, having made sure, 25 years ago, of a nest egg that now gave him 1,000 US$ a month, a handsome sum. “Argentina es un adolescente.” Vila smiled and went to dance with a pretty girl of around twenty-five. A man of his age in England cuts a sorry figure. Years of doubt and fear, worrying as a way of life, oh but this, and what if that, and you can’t be too careful and no, I don’t think so, thank you, have make the English old. Give me Argentina, this youth! They may shy away from work, but they don’t shy away from life.

Ricardo is back at the table. It is a Wednesday night, around 1.30 am, and no one, young or old, all in the same dream, is in a hurry to go.

“How many of these people have to get up early tomorrow?” I asked him.

“None of them,” he looks pained. “Only me.”

After la Machadera, Casa Paraguaya

5 am belongs to the scooters. If they have just one rider, it’s preferable to zip along in mini-gangs of, say, three machines. Single scooters, however, with their statutory load of three people, straining the engine to maximum, score highest. No one over twenty-five, helmets must not be worn or carried, and under no circumstances must lights be switched on.

At Saturday lunchtime, Rosario’s shops are all locked up. Breakfast is saved by the heroic 24-hour pastelería with its stodgy pastries and heavy, sticky cakes. Tea and apple cake on a broken plate. Tiny flies and mosquitoes, trapped in the amber of the apple jelly, have to be prised loose with a fork.

I stray to a tired district where commerce struggles to be presentable and faces are lined by long working hours. Broken pavements, massive stone lions atop the Casa de España, buses launched along narrow thoroughfares, and an unidentifiable shop called “Very.” I waft along, borne by the soupy warmth.

Everything is in the balance. If it tips over too far, the crumbling façades of edifices and middle-class mores will turn inside out to show guts of unpretty poverty. A bus I was on passed by a barrio outside Buenos Aires that wanted respectability but had yet to take the determining step into it. Low, modest dwellings were placed carefully in grids of swept streets, like houses of cards in a single, glued-together layer, not quite flimsy but awaiting to be made permanent, using the existing structures as bones and scaffold. Give the men and women here some sustained work, a reason to believe in continuity, and that door would be replaced by a better one, this roof would be fixed, that father would spend some money on paint and watch his house come to look more like a home in a neighbourhood that has just gained a corner shop. When there are grounds for hope in a life in common, a person feels like a citizen. Neighbours will look each other in the eye and make a greeting. They will talk together about better provision for children, petition the council for better street lighting, go to work with a sense of purpose. Buy a new mattress, pay off a debt, think about a car and goodbye to the scooter. Swimming lessons for the girls.

But it has only to tip the other way and this future’s eggshell is broken. Wages don’t keep up with inflation, then the new law curtailing indemnification means that reasonably well-paid workers are axed to replace them with desperate aspirants who will take less; record exports and healthy investment are publicized in the press but none of the benefits reach lower down the food chain; multiple hours worked on decreasing energy no longer make sense when the children can’t have new shoes and it’s gnocchi again. Who has work around here these days? Who stole the wheels from that car? No one repairs anything, there are fewer people in the streets at night, you keep the door firmly locked and your children note the worry in your face when the fights and the drugs start after dark. The neighbour has long forgotten her invitation to you to come round and the trash collected by the wind in the corners is less and less distinguishable from the shambles in which you are living. Even your husband no longer looks at you with the same softness as he did.

The Paraná is high, carrying a one-way traffic of matorral and sizeable vegetable chunks of delta dragged from their rooty mooring. Nati once saw a cow pass by, marooned on a tiny drifting island.

A plane flies against the current, exhorting us to go to the Superpark on Thursdays.

We crossed the bridge in driving rain, a hint of brown suggesting the swelled river. Onwards to lush, green vistas in wet eyes. Ever onward, desirous of disappearing over that hill and leaving home behind for good. The ever-receding reward of perseverance. Naïve dreams of celebrating life and liberating love. Emotional belief patterns that survive intellectual disavowal.

Today I lunched with Angel, a fat Peruvian. He has the modest ambition of opening a pet shop. His attempt to do so is proving as similarly Kafkaesque as mine to rent an apartment. Somehow, it just doesn’t happen. The money doesn’t arrive in a bank account, or a current gas bill is demanded, or a deed to guarantee the deal, or the property is let to someone else and in any case, and especially after your long trek here, Sr. Bostic is not in.

Tramp them streets in the rain and wonder.

Although K really ought to have been chasing down an electric bill (so much better than gas!) for a property belonging to someone he didn’t know and which was destined to support his rental application in exchange for a certain sum in pesos and an entitlement to marriage or soul, whichever haddeth the greater value, he splashed a path to the station, boarded a bus to a town on the border with Uruguay, and stared through the opaque windows as it rode over the bridge.

The riverside town was made up of wet houses and dogs. An unsmiling girl of twenty-five, wanting her dullness shared, had him accompany her through rain and muddy streets to the thermal baths that were the pride of the resort. Here, at least, human bodies were joined in communal rite, with warm waters spouting from a ring of gushers overhead or lapping to the rim of a round, shallow pool. Freed of clothes and social labels, old and infant, all curious shapes and sizes, stood or sat in the steamy spa and let the glass panes of the roof bear off the falling rain. The girl, thankfully, showed no sign of wishing to converse, leaving K to wallow.

The day would be darkening on his application in the city. At this hour, his inexcusable omission in leaving no contact telephone number for the agencies would be croaking loud in their ears, and changing its chameleon colour from inadvertent blue to blatant red.

I encouraged Angel to vamp up his pet shop — if he ever gets one, and there must already be one for every fifty inhabitants in Rosario – with innovative stock such as dwarf giraffes, multi-coloured seals, ostriches trained to give advice on dress sense (“Make a move for those socks and I’ll swallow them before you can you blink.”) He was more interested in the waitresses’ arses and sneaking a smoke on his herb pipe. He had been kept awake at the hostel by young Israelis on beer and cocaine (they had a guitar, can you imagine?) and I was sitting in smugly clean clothes, having moved into a temporary room all to myself in a city centre apartment down a dingy passageway, where I had been able to open my suitcase for the first time in six weeks. This is progress and I claim it. I cannot contact the woman about the dodgy guarantee, of course, and tomorrow is Saturday, but nonetheless and fair’s fair, is it not? and all the same, and it’s only dogs and children squealing down the hall, so let’s be thankful.

Then all of a sudden there’s a night out dancing bacchanalian folklore with hats and girls. Next day, the rain dries to dress the faded grandeur of façades in sunlight.

Another night and I am transported to another milonga, showered with powder and a sprig of peppermint stuck behind my ear. Ricardo sits and thinks of another bottle of beer. Cartucho has stars in his eyes. The dance between girls and boys twists and turns.

“Los argentinos, somos ladrones” insists Andrea. Which she, as a gestora, most certainly is.

22nd March

The hall, which occupied the street corner and must double as a café-restaurant by day, was high-ceilinged, capacious and dimly lit. A red light lent its hue to an empty area of seating. Along the wall of, a grand length of scarlet material was draped in languid, funereal fashion. We sat against a large window from where we could observe the milonga’s expanse, couples and friends occupying the other tables, or twisting and halting, turning and leaning, all of them, whether seated or dancing, implicated in the ritual and its mournful music. We joined Ricardo and Vila and ordered wine. Sabina sat with a half-smile in the company of men more than twice her twenty-one years and waited for it to begin.

“I don’t like this music,” Ricardo opined dutifully. Accordion sounds and light percussion played out a characteristic tango over loudspeakers. “It is alright to listen to, but not to dance.” One couple moved round the floor holding each other close, as if exchanging confidences; a short, squat man arranged himself like a ladder against a full-bodied woman, a head taller than him, and stuck an arm out high to lead her onwards; one pair of dancers moved with carefully hurried steps, as though picking their way barefoot over hot sand, while another worked slowly, introspectively in a small space, through the set pattern.

“This is like something from 1910,” Ricardo complained.

“This was written 30 years ago,” Vila said. “They just play it that way.”

“It’s not tango,” insisted Ricardo. Yet he complied unhappily when Sabina proposed a dance.

It is the tang which makes tango. The solemn obligation to accompany another in a prescribed, formal design to the chords of jaunty melancholy, in an old dance hall redolent of passionate affairs, held by its players tonight in an ambience of decorum by preference. The woman and the man, lovers or strangers, do as they must. Unsmiling and with undisclosed feeling, they will complete the moves before standing back from each other and waiting for the music to begin again.

Vila wore a black shirt tucked into dark grey slacks. Strong and well-built, looking a decade younger than his sixty-nine years, he might have been a retired cop, but he had been a tango dancer and singer. He must have seen the look on my face as I admired the scene: “Es la joda siempre. People just want to go out at night and dance.” Ricardo, El Flaco, and Sabina, little Rampilón, dipped and rose on the floor. He, tall and tragic in his thinness, balding and mustachioed, led her at courteous remove; she with finger tips placed behind his shoulder. Their silent voices sing; he calls high notes and she answers low. Leggy bird and earthbound mammal. I think he may be secretly in love with her.

“Argentinians don’t want to work. This could be a very prosperous country. But give someone the chance to make good money by coming in and working hard from 9 to 6 and they throw up their hands,” Vila gestured like someone refusing an unfair, excessive demand. Nobody’s interested: just as long as there’s a milonga to go to…”

“So how do people get by?”

“Everyone has something or other sorted out. They’re lazy, but they’re not stupid. They have an eye for the main chance. Today, I got up late, played the piano until four, went for a swim, met some friends, had a nap and came out here.” He laughed, as well he might, having made sure, 25 years ago, of a nest egg that now gave him 1,000 US$ a month, a handsome sum. “Argentina es un adolescente.” Vila smiled and went to dance with a pretty girl of around twenty-five. A man of his age in England cuts a sorry figure. Years of doubt and fear, worrying as a way of life, oh but this, and what if that, and you can’t be too careful and no, I don’t think so, thank you, have make the English old. Give me Argentina, this youth! They may shy away from work, but they don’t shy away from life.

Ricardo is back at the table. It is a Wednesday night, around 1.30 am, and no one, young or old, all in the same dream, is in a hurry to go.

“How many of these people have to get up early tomorrow?” I asked him.

“None of them,” he looks pained. “Only me.”

After la Machadera, Casa Paraguaya

5 am belongs to the scooters. If they have just one rider, it’s preferable to zip along in mini-gangs of, say, three machines. Single scooters, however, with their statutory load of three people, straining the engine to maximum, score highest. No one over twenty-five, helmets must not be worn or carried, and under no circumstances must lights be switched on.

At Saturday lunchtime, Rosario’s shops are all locked up. Breakfast is saved by the heroic 24-hour pastelería with its stodgy pastries and heavy, sticky cakes. Tea and apple cake on a broken plate. Tiny flies and mosquitoes, trapped in the amber of the apple jelly, have to be prised loose with a fork.

Buenos Aires, 27th March

I did a day’s work. Yes: and it could get worse. I don’t think I can kiss any more beards. Dorina, our Maecenas, started to tell me about what she had to deal with at her fashion design studio. Material espesa, she explained. Was it corduroy? No, an invisible denseness that she had to battle with. It took it out of her. Our studio, the one doing myriad things, was her haven, even though it brought the number of paid staff up to 47, another weight on her spirit. Here, it came from the heart (she indicated her heart); there, it was too much (pointed to head), when it needs to be more (cunt and heart). She pointed to her cunt, I swear it. She wrote poetry without thinking. I do a lot of things that way, I said. Over lunch, with Alfredo and I, (she spinach goo, Alfredo pasta, me meat sandwich & chips), she said that the body was more than just this (she refrained now from pointing), it was a condensation of spirit. She paused and looked at us, expecting one of us to take up the comment and carry it forward. I looked at Alfredo. He burbled something, clutching his plastic box of pasta: something unintelligible, but enough to encourage her to assert the non-religious nature of Buddhism.

All the guys have beards and they kiss when they come, kiss when they go. Tomorrow, I need to eat out and miss the beards.

I did a day’s work. Yes: and it could get worse. I don’t think I can kiss any more beards. Dorina, our Maecenas, started to tell me about what she had to deal with at her fashion design studio. Material espesa, she explained. Was it corduroy? No, an invisible denseness that she had to battle with. It took it out of her. Our studio, the one doing myriad things, was her haven, even though it brought the number of paid staff up to 47, another weight on her spirit. Here, it came from the heart (she indicated her heart); there, it was too much (pointed to head), when it needs to be more (cunt and heart). She pointed to her cunt, I swear it. She wrote poetry without thinking. I do a lot of things that way, I said. Over lunch, with Alfredo and I, (she spinach goo, Alfredo pasta, me meat sandwich & chips), she said that the body was more than just this (she refrained now from pointing), it was a condensation of spirit. She paused and looked at us, expecting one of us to take up the comment and carry it forward. I looked at Alfredo. He burbled something, clutching his plastic box of pasta: something unintelligible, but enough to encourage her to assert the non-religious nature of Buddhism.

All the guys have beards and they kiss when they come, kiss when they go. Tomorrow, I need to eat out and miss the beards.

31st March

Misiones, 45

A garret. I wouldn’t mind a garret. This room is more like a cell with its single high bunk, narrowness—stretching out my legs I can touch both walls—and an upper arched window showing grey sky. From two flights of stairs on entering the house, I pass through a corridor cluttered with empty bottles, bags of roof rubble and paint buckets soaking underwear as far as the fixed stepladder up to my box, which I have to climb in little lurches, pulling up monkey-like, hand-over-hand on the single railing. Once boxed, I have a corner triangle of cheap chipboard covered in white plastic to sit at and type these words—and three more wobbly steps up to the bed. There is a red-and-green thing on the wall that is too ugly to even pretend to be art. Looking up, there is a plasterboard ceiling and an artificial rose as cord-pull for drawing the curtain on the gridded, metal-gauzed window.

Misiones, 45

A garret. I wouldn’t mind a garret. This room is more like a cell with its single high bunk, narrowness—stretching out my legs I can touch both walls—and an upper arched window showing grey sky. From two flights of stairs on entering the house, I pass through a corridor cluttered with empty bottles, bags of roof rubble and paint buckets soaking underwear as far as the fixed stepladder up to my box, which I have to climb in little lurches, pulling up monkey-like, hand-over-hand on the single railing. Once boxed, I have a corner triangle of cheap chipboard covered in white plastic to sit at and type these words—and three more wobbly steps up to the bed. There is a red-and-green thing on the wall that is too ugly to even pretend to be art. Looking up, there is a plasterboard ceiling and an artificial rose as cord-pull for drawing the curtain on the gridded, metal-gauzed window.

Luciano tells me that Dorina has asked him to write a poem. Without overtly saying as much—so that he and she can discern anything that might bother him and help him to be happier at work. Hey, this was my idea for a private practice of psychopoetry! In the workplace, however, it is therapy imposed. The poem can be anything, apparently, “que me siente libre.” Had I not yet been with her and brother Leo for one of their mystic chats? I am clearly going to have to stick it out and struggle through turgid undergraduate analyses to see what else might be there. Later, Dorina, Gaspar, and Sebastian turned up to give me a house-warming and we went on Enrique’s suggestion to La Bella Gamba. Low lit with lamps, it looked smart from outside, but the poor illumination simply obscured a vague sleaziness, self-service booze and microwave your empanadas or plate of congealed cheese. Over rock nacional at full volume and distributing Coca-Cola (I went and got myself a bottle of red), Dorina asked if we had meditated over an extended period of time. I decided to let Sebastian and Luciano handle this one. Fifteen seconds later, none of us had managed a single word. This fashionable new-age crusading becomes as obsessive as any other “answer.” Like all partial truths wanting to be the truth, it excludes and disapproves of what it does not like and denies itself the liberation of laughter.

8th April

I like it that I can go out and get a packet of little cakes filled with dulce de leche from the Chinese supermarket and when I get back the tea is still hot.

The first time I go for a bike ride, the pedal falls off.

Always open, at four in the morning, are the street plant sellers.

I like it that I can go out and get a packet of little cakes filled with dulce de leche from the Chinese supermarket and when I get back the tea is still hot.

The first time I go for a bike ride, the pedal falls off.

Always open, at four in the morning, are the street plant sellers.

A new development! The metal divide at the top of my stairs had a pinhole of light tonight. When I put my eye to it, I see a Chinese girl next door in a kitchen and the smell of Chinese cooking drills through the infinitesimal opening.

Scavengers and street sweepers. In a city that has no rubbish bins, theirs is a noble profession. Dull grey days give way to more of the same, only sultry and mosquito-ridden. The air is so contaminated that it acquires visibility.

A civic solidarity obtains within the confines of the bus. Seats are surrendered to those who have greater need as a matter of course.

Water starts dripping on the bottled water in Coto. Then a cataclysmic CRACK and a deluge. The entrance to the supermarket is flooded in seconds and I walk out in T-shirt and hat to the heaviest downpour I have ever known. The short stretch along Yrigoyen is brimming. On Misiones, water pours out from beneath front doors. The whole of the Subte system closes down and power failures black out whole chunks of the city. 35 mm in one hour makes for a 32°C sauna. Later, during a respite, when Enrique and I venture out for a few games of pool, the sky beyond Rivadia is lit up by streaked lightning against a gently purple sky.

The following day, the sun shone brilliantly in the park, where a fountain bubbled in sparkling light, the trees glorious, the grass lime green. The sky was washed blue again and a girl with a great slobbering dog crossed the road.

If it gives us vitamin D, there is a sense in which we eat sunlight.

The merry-go-round on the Plaza de Mayo, its wooden horses that go up and down.

The city, all the city some of the time and certain parts of it all of the time, exists in a much older era.

Vicki leaves little wet footprints all the way from the bathroom. I find this unbelievably endearing.

Scavengers and street sweepers. In a city that has no rubbish bins, theirs is a noble profession. Dull grey days give way to more of the same, only sultry and mosquito-ridden. The air is so contaminated that it acquires visibility.

A civic solidarity obtains within the confines of the bus. Seats are surrendered to those who have greater need as a matter of course.

Water starts dripping on the bottled water in Coto. Then a cataclysmic CRACK and a deluge. The entrance to the supermarket is flooded in seconds and I walk out in T-shirt and hat to the heaviest downpour I have ever known. The short stretch along Yrigoyen is brimming. On Misiones, water pours out from beneath front doors. The whole of the Subte system closes down and power failures black out whole chunks of the city. 35 mm in one hour makes for a 32°C sauna. Later, during a respite, when Enrique and I venture out for a few games of pool, the sky beyond Rivadia is lit up by streaked lightning against a gently purple sky.

The following day, the sun shone brilliantly in the park, where a fountain bubbled in sparkling light, the trees glorious, the grass lime green. The sky was washed blue again and a girl with a great slobbering dog crossed the road.

If it gives us vitamin D, there is a sense in which we eat sunlight.

The merry-go-round on the Plaza de Mayo, its wooden horses that go up and down.

The city, all the city some of the time and certain parts of it all of the time, exists in a much older era.

Vicki leaves little wet footprints all the way from the bathroom. I find this unbelievably endearing.

The lift went up to the 11th and top floor, which is where I work. I opened the doors to find the floor at chest height. I closed the doors again to give the lift another chance to hitch up the last couple of metres. It went down. When it reached the ground floor, I was all set to hit the 11th floor button again, but it needed no prompting, bouncing straight back up again. This time, when it reached the top, before I opened the doors, it started going back down again. I hit a button at random: 8, got out at that floor, and walked up.

30th April

My courtesy with the sour-faced portero was rewarded today, when he asked me if I was English, and beckoned me over to look at something. I am a fanático he said, a hooligan. Liverpool, was my guess. That or Arsenal. He rummaged around and brought out a crumpled programme for a concert in Buenos Aires last month. Tom Jones. At first, I didn’t understand. Then he made clear, spectacularly clear, that he was, and always had been, Tom Jones’s biggest fan. He had all the music, knew all about him. He admires the English, he tells me. For their honourable soldiership, sparing bloodshed in the Malvinas. For their professionalism. For what? God knows. I had met this attitude in lesser measure before and hadn’t known what to say then, either. I wished him happy workers’ day tomorrow and went off on my bike.

30th April

My courtesy with the sour-faced portero was rewarded today, when he asked me if I was English, and beckoned me over to look at something. I am a fanático he said, a hooligan. Liverpool, was my guess. That or Arsenal. He rummaged around and brought out a crumpled programme for a concert in Buenos Aires last month. Tom Jones. At first, I didn’t understand. Then he made clear, spectacularly clear, that he was, and always had been, Tom Jones’s biggest fan. He had all the music, knew all about him. He admires the English, he tells me. For their honourable soldiership, sparing bloodshed in the Malvinas. For their professionalism. For what? God knows. I had met this attitude in lesser measure before and hadn’t known what to say then, either. I wished him happy workers’ day tomorrow and went off on my bike.

May

One of those universal café phenomena. A girl’s flat voice rolling its solid tyres over the terrain of her recent consciousness, while her two friends sit with their backs to you and do not speak a word the whole time. When the girl gets up to go, one half expects her to pick up the double floppy dolls and carry them off with her.

That gentleman bohemian look of anyone worthy of the name el flaco, in which the dapper is second to the unkempt, bright, searching eyes and hair tufting vigorously out behind the ears on a tall, thin man no younger than mid-thirties.

An odour not unlike boiled cabbage or sewerage passes the day in my room and I open window and door to breeze it out, only to close them again when Sandra starts cooking. Every culinary treat she prepares billows a miasma of sourness up the stairs. Once, when I was in the sitting room as she ate, I checked to see if she had taken off her shoes, but it was the food.

One of those universal café phenomena. A girl’s flat voice rolling its solid tyres over the terrain of her recent consciousness, while her two friends sit with their backs to you and do not speak a word the whole time. When the girl gets up to go, one half expects her to pick up the double floppy dolls and carry them off with her.

That gentleman bohemian look of anyone worthy of the name el flaco, in which the dapper is second to the unkempt, bright, searching eyes and hair tufting vigorously out behind the ears on a tall, thin man no younger than mid-thirties.

An odour not unlike boiled cabbage or sewerage passes the day in my room and I open window and door to breeze it out, only to close them again when Sandra starts cooking. Every culinary treat she prepares billows a miasma of sourness up the stairs. Once, when I was in the sitting room as she ate, I checked to see if she had taken off her shoes, but it was the food.

19th May

I cycled past Plaza Garay at about eight in the evening. In the middle of the square was a man with a microphone and amp. This is a sure-fire puller for Latinos: and we are in little Peru here. He was preaching something about the army of heaven, and I was delighted to see that he was entirely on his own.

The rats encroach further. Yesterday, they nibbled one of my apples. Enrique’s strategem of apple-baited traps only attracts them. Today, there is a mini trail of mierdacitas from outside my door down the steps.

The sun is strong and dirty. It bleeds a black graininess onto the skin.

I can hear below Sandra steamrolling Enrique with her tanking German Spanish. Unfailingly grammatically accurate and those hard rolling final r’s laid out in the timid air as iron, consequential argument. Yet my money’s on Quique. He is more arrogant than she is fired-up; his pig-headedness beats her conviction every time. He is at one with the supremacy of his knowledge. And yet: her volume is an assault. No vowel is left unvoiced. Her consonants have three dimensions. She is on one tonight. Earlier, on the phone: there are few sounds less appealing, more unnerving, than an enthusiastic German.

I look up cajeros for the Banco de la Nación. There is one at Rivadavia 11078. Verily, the city goeth on forever.

“Este pais no tiene arreglo,” said one woman in the bank queue. “Se murieron trece personas en las calles por el frío.” The next woman was unsympathetic. “Es que no quieren trabajar. Es el facilismo. ¿Quién quiere levantarse para trabajar a las cinco de la madrugada?”

I cycled past Plaza Garay at about eight in the evening. In the middle of the square was a man with a microphone and amp. This is a sure-fire puller for Latinos: and we are in little Peru here. He was preaching something about the army of heaven, and I was delighted to see that he was entirely on his own.

The rats encroach further. Yesterday, they nibbled one of my apples. Enrique’s strategem of apple-baited traps only attracts them. Today, there is a mini trail of mierdacitas from outside my door down the steps.

The sun is strong and dirty. It bleeds a black graininess onto the skin.

I can hear below Sandra steamrolling Enrique with her tanking German Spanish. Unfailingly grammatically accurate and those hard rolling final r’s laid out in the timid air as iron, consequential argument. Yet my money’s on Quique. He is more arrogant than she is fired-up; his pig-headedness beats her conviction every time. He is at one with the supremacy of his knowledge. And yet: her volume is an assault. No vowel is left unvoiced. Her consonants have three dimensions. She is on one tonight. Earlier, on the phone: there are few sounds less appealing, more unnerving, than an enthusiastic German.

I look up cajeros for the Banco de la Nación. There is one at Rivadavia 11078. Verily, the city goeth on forever.

“Este pais no tiene arreglo,” said one woman in the bank queue. “Se murieron trece personas en las calles por el frío.” The next woman was unsympathetic. “Es que no quieren trabajar. Es el facilismo. ¿Quién quiere levantarse para trabajar a las cinco de la madrugada?”

June 4th

Carlos Calvo 11th floor

As good a place as any to be struck once more by the would-be beauty of a tragic metropolis. The scope of a real cityscape. A comic-book urban night where red lights blink atop the high rises.

Quique called out of friendliness in case I felt alone in the new place. Now that was nice of him. I was snug as a bug, taking in the dark vista with a chow mein, a bottle of tinto and Rock art and the X-ray Style playing behind me.

Carlos Calvo 11th floor

As good a place as any to be struck once more by the would-be beauty of a tragic metropolis. The scope of a real cityscape. A comic-book urban night where red lights blink atop the high rises.

Quique called out of friendliness in case I felt alone in the new place. Now that was nice of him. I was snug as a bug, taking in the dark vista with a chow mein, a bottle of tinto and Rock art and the X-ray Style playing behind me.

1st July

My Sunday routine is to stroll through the rastro, seeing the same performers as every other week, the bubble lady, the smiley singer with the short hair, the hug-givers, the painter of semi-erotica on wood, the old girl banging on pots, the windy people, the puppeteer with the drunk character, the magnificent Spanish guitarist, the old girl posing rather than dancing, the tango dancer with the dummy. Today we had a new act, magicians. I spent a spell in Parque Lezama, getting beaten at chess by Luis with the crutch. A bife de chorizo, vino and tiramisu at La Farmacia for 21 pesos can’t be beaten. Then an hour stuck in the lift before being able to call Wendy who is surviving, as best she can, our mother’s visit. Another crushing at chess, this time from computerized Fritz, a delivery of empanadas, Malbec and an episode of Dark Angel. The Space Needle may be higher, but the night view I have from up here is so very much like the one she has up there.

My Sunday routine is to stroll through the rastro, seeing the same performers as every other week, the bubble lady, the smiley singer with the short hair, the hug-givers, the painter of semi-erotica on wood, the old girl banging on pots, the windy people, the puppeteer with the drunk character, the magnificent Spanish guitarist, the old girl posing rather than dancing, the tango dancer with the dummy. Today we had a new act, magicians. I spent a spell in Parque Lezama, getting beaten at chess by Luis with the crutch. A bife de chorizo, vino and tiramisu at La Farmacia for 21 pesos can’t be beaten. Then an hour stuck in the lift before being able to call Wendy who is surviving, as best she can, our mother’s visit. Another crushing at chess, this time from computerized Fritz, a delivery of empanadas, Malbec and an episode of Dark Angel. The Space Needle may be higher, but the night view I have from up here is so very much like the one she has up there.

Where else in the world would you see two cops going into the station kiss each other? Of course, they’d beat the shit out of you at the drop of a peaked cap.

July 15th

I do like telephone exchanges. Getting to know a city by its dialling codes, knowing that when I call 4803 it’s an area of Palermo. I like being 4307 and knowing that it is my neighbourhood. In Madrid Carabanchel Bajo was 525.

I have to leave before the Chinese laundry loses all my socks.

Dorina arranges my papers so that I work from Colombia. Never have I have been treated so fairly or generously by an employer.

July 15th

I do like telephone exchanges. Getting to know a city by its dialling codes, knowing that when I call 4803 it’s an area of Palermo. I like being 4307 and knowing that it is my neighbourhood. In Madrid Carabanchel Bajo was 525.

I have to leave before the Chinese laundry loses all my socks.

Dorina arranges my papers so that I work from Colombia. Never have I have been treated so fairly or generously by an employer.

20th August

A sadness takes hold of me tonight and I know that it is this city and these poor, troubled people. The dead who won’t go away. Earlier, I took the subte to Congreso de Tucumán and walked to Av. Libertador and the Escuela de Mécanica de la Armada. Now I have seen it. It exists. It happened. One of the reasons I felt I had a compromiso with going there was the fact that a lot of those youngsters were my age. They were all killed between 76 and 83, coinciding with my university years 78 - 82.

A sadness takes hold of me tonight and I know that it is this city and these poor, troubled people. The dead who won’t go away. Earlier, I took the subte to Congreso de Tucumán and walked to Av. Libertador and the Escuela de Mécanica de la Armada. Now I have seen it. It exists. It happened. One of the reasons I felt I had a compromiso with going there was the fact that a lot of those youngsters were my age. They were all killed between 76 and 83, coinciding with my university years 78 - 82.