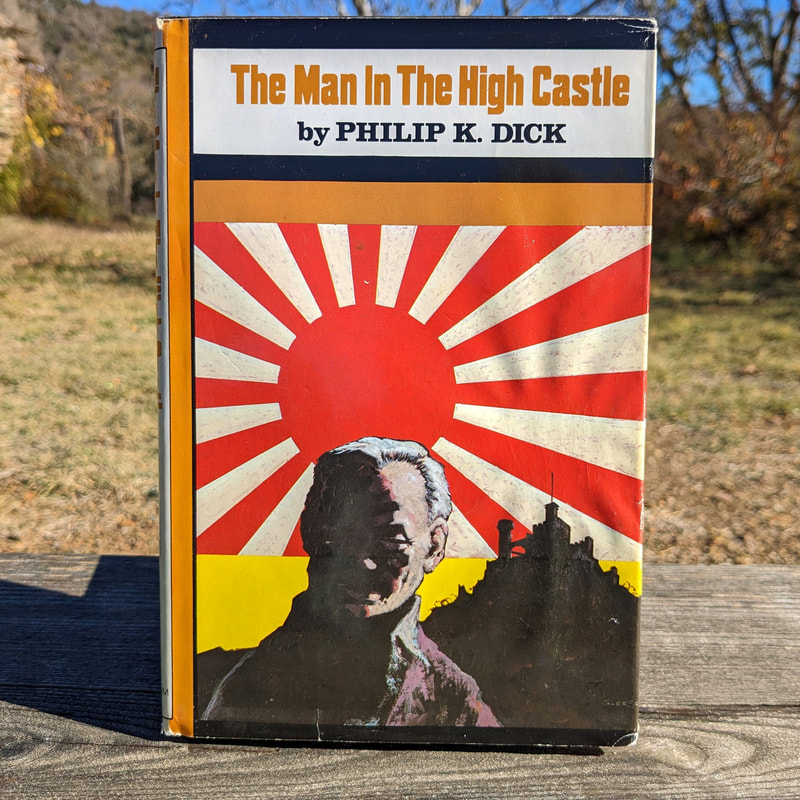

1962 First edition 1962 First edition One of Dick’s finest is a flawed favourite of mine.

Once, around the age of thirty, I discovered Philip K. Dick, I was blissfully fixated, reading one title after another, knowing that any book with his name to it would delight me, a sensation I hadn’t known since I was a kid and read The Famous Five or the Three Investigators, and wouldn’t again until I came across Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey & Maturin multi-book epic. Unlike these, Dick’s books weren’t a series. Instead, they were conjoined by one man’s voice and vision and common to them all was a pace and an intrigue carrying the story along, and an empathy for his protagonists which meant that that their fate was taken seriously no matter how outlandish their predicament. There was also a wave of humour that passed through the narratives like the sweep of a radar and caused them to sparkle and smile in places. This one was different. Dick’s characteristic weirdness and its accompanying comic element are absent, for he is considering an alternative fate of our world that would have been no laughing matter. After a cursory look at the blurb, I remember opening The Man in the High Castle hungrily at page one and starting to read. Here, as usual, we were in Dick’s 1950s/60s California––only it was unusual. There was something odd about the writing that I couldn’t put my finger on: and then it clicked. His American store owner was speaking and thinking with Japanese speech patterns and inflection. In this version of history, the Allies lost World War II, after which the western half of the USA was allotted to the Japanese and the eastern to Germany. The colonizers’ cultural mores have become established in the Pacific Sates of America and Mr Childan bows spontaneously to his high-ranking Japanese customers. The plot thickens nicely until the denouement, which I found inexplicably weak and disappointing. Later, I think I discovered why. Dick’s imagined history manages to be both entertaining and chillingly thought-provoking. Africa is referred to as a “Nazi experiment” which went too far even for them and does not bear speaking about in detail. A Rosenberg pamphlet regrets, “Unfortunately, however ––”: and leaves it there. “That huge empty ruin” is the stark image that we are given. History, of course, could well have gone the other way. In which case, my Royal Navy father wouldn’t have survived and I wouldn’t be here writing this. Had the Germans wiped out the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk and Britain sued for peace (as it very nearly did: Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, was all for it), Hitler’s war machine may have grown invincible. The eponymous Man in the High Castle, Hawthorne Abendsen, has written an alternative alternative history, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, in which the Axis powers lost. That it didn’t quite turn out the same way as our own history goes to the heart of what Dick is exploring in the novel: the idea of a multiverse in which parallel realities coexist, or of a fictional reality that we inhabit unknowingly. What makes Abendsen’s proposition fascinating is that it turns out to be true. What makes it fall so terribly flat is the way that the ending is handled. Hawthorne’s character (apathetic, “not sure of anything”) is insufferably feeble and so is the novel’s culmination. Dick’s boldness and deftness of touch desert him at the worst possible moment. The Chinese I Ching plays a mystical, oracular role in the narrative. Dick justifies its presence in Japanese culture by smuggling in an animist Shinto idea: “Spirit animates it”, but it’s ultimately out of place. It seems that Dick, like the fictional Abendsen, wrote his novel casting the I Ching to determine the outcome of events and this whim is, I suspect, is what let him down. If he had trusted his own nous rather than the oracle, I am sure that the ending would have been immeasurably stronger. As it is, faced with the reveal and its huge implication, Abendsen is blasé, heedless of danger, and the novel simply peters out.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed