|

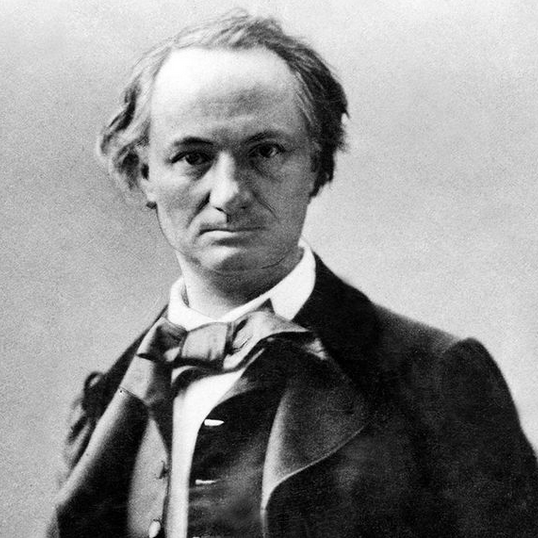

Baudelaire’s poetic oeuvre of more than a hundred poems originated in a condition clearly stated in a preface and which he called “l’ennui.”

“Boredom” is a broad concept here. It covers just about every kind of psychological jolliness from frustration to abysmal despair, passing through disenchantment, depression and mal de vivre. Having syphilis probably didn’t help. He was not a happy bunny. In “The Flowers of Evil” (a dream of a title), Baudelaire sets out his experience of being sick of life and his different and equally futile ways of combating it: striving for the ideal (beauty, freedom, immortality: not asking much, then), repudiation of the crassness of modernity, drinking, sex, religious rebellion, and a courting of death. Thus he cultivated melancholy, the beast that, fed on consolations, grows only stronger: “La jouissance ajoute au désir de la force” (Le Voyage) You just have to feel for this paragon of French Romantic poets, whose suffering was never going to be relieved by the fulfilment of desire, not by his art, his opium or even the carnal Jeanne Duval. Had Buddha been there to instruct him, he might have learned that no manner of struggle, pleasure, narcotic, denial or other manipulation would resolve dukkha, so long as it is the symptoms that are addressed and not the root cause. Or he might equally, like many of us, have persisted in his profound dissatisfaction and dissolution — and where better to do that than amidst the decadent poetic society of mid-19th century Paris? Our Charles was seriously committed to his libertinage and his personal truth. The particular impact of his poetry comes from employing the classical metre of 12-syllable alexandrine verse, often in sonnet form, for an elegant expression of what was then considered to be immoral and even depraved content. “Bizarre déité, brune comme les nuits, Au parfum mélangé de musc et de havane, Oeuvre de quelque obi, le Faust de la savane, Sorcière au flanc d'ébène, enfant des noirs minuits," (Sed Non Satiata) [Strange goddess, dusky as the night, Scenting of musk, of cured havanah Conjured by obeah, Faust of the savannah Ebony-flanked witch of black midnight] “«Moi, j'ai la lèvre humide, et je sais la science De perdre au fond d'un lit l'antique conscience.” (Les Métamorphoses du vampire) [With my wet lips and learned science I will relieve in a bed the hardest conscience] By making subjective experience the supreme criterion, Baudelaire sounds always modern. His language is both sumptuous and splenetic, accomplished and vernacular, making free use of vocabulary of the urban everyday: "Quand le ciel bas et lourd pèse comme un couvercle Sur l'esprit gémissant en proie aux longs ennuis," (Spleen) [When the low sky weighs heavy like a lid Upon the soul stretched out by suffering] Proper poète maldit that he was, Baudelaire had half a dozen of these poems banned. He was found guilty of offending public decency and fined (the bourgeois could afford it and it did wonders for sales). The sensibilities of virtuous French citizens required such protection that the six banned poems of 1857 were not permitted publication until 1949.

0 Comments

Villon was a well-educated, humorous rogue who fought and stole his way to a well-earned prison cell. While he waited to be hanged, he wrote a quatrain for the ages:

Je suis Françoys dont il me poise, Né de Paris emprès Pontoise; Et de la corde d’une toise Sçaura mon col que mon cul poise. [For my sins, I am Francis Born near Pontoise, in Paris And by a rope to end my days My neck will know what my arse weighs] Somehow he always managed to get his crimes pardoned or his sentence commuted. Villon’s most famed work is his lengthy Testament whose jokes and jibes aimed at 15th century contemporaries don’t mean much to us today, while of interest are the fair ballads it contains, one of which bears the grand old refrain: “Mais où sont les neiges d’antan?” [But where are the snows of yesteryear?] Where indeed? Nerval had his ups and downs, nervous breakdowns and penury. He wrote some regrettable poetry, made a translation of Faust that Goethe apparently considered superior to his original, knew serial unrequited love, and then produced in Les Chimères a set of sonnets that are quite remarkable.

Ride with the classical references and let through the esoteric power, immediacy and music: “Je suis le Ténébreux, - le Veuf, - l’Inconsolé, Le Prince d'Aquitaine à la Tour abolie: Ma seule Étoile est morte, - et mon luth constellé Porte le Soleil noir de la Mélancolie.” (El Desdichado) Yowza! Nerval deserves a mention in any history of French Romanticism for having a pet lobster which he took for walks in Paris. He liked Thibault the lobster because it knew “the secrets of the deep.” It was 1980 and I was now a card-carrying Existentialist. Or terminally depressed. Take your pick.

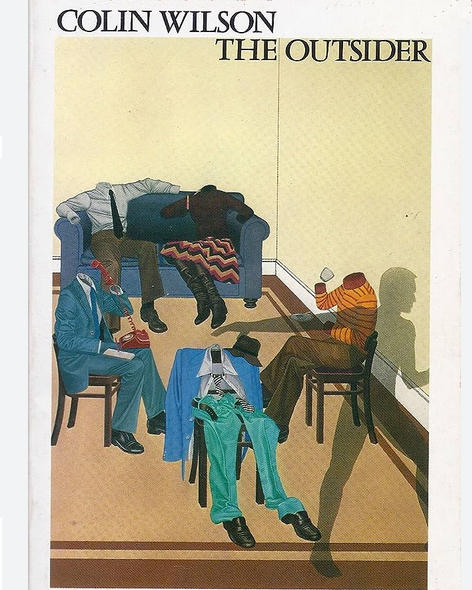

Always wanting to comprehend or vindicate my hopeful despair, I relished this book and its aim to make ontological sense of all the lost and suffering souls of great literature by means of a unifying factor, an e=mc² of spiritual anguish and desolation. The book’s thrust and argument was that from Raskolnikov to Josef K, from l’Homme Révolté to Steppenwolf, one could identify a single intersection of their multifarious Venn diagrams. Here, in this metaphysical enclosure, stood the solitary figure of the Outsider: an epiphany explaining... well, not a lot really, other than he (it tended to be a “he”) existed. What the outsiders in Romantic and Absurd literature were collectively outside of, Wilson didn’t say, so one can only extrapolate. A world of injustice, lies, mediocrity, hypocrisy? Where God is dead and only a void obtains? An anarchic cosmos in which morality is individually random and salvation a foolish phantasm, where mankind strives in denial and only the long, cold death of the universe awaits all meaningless creation? What the hell. Here were Nietzsche, Dostoevsky, Camus, T.S Eliot, Kafka, Blake, Hermann Hesse, Sartre... Gadzooks, Wilson had put all the heavyweights on my side. If I wanted, I could now be justifiably miserable for the rest of my life. Thatcher was in power, the bin men were on strike, the National Front were marching and Johnny Rotten was proclaiming “No future.” If no meaning could be found in an alienated existence, then there was no hope. Such was my experiential conviction. I really was a whole bundle of joy in those days. The thing was, I had an abiding sense of being a fraud at Oxford and not belonging anywhere, a believer in nothing with the absurd as my black flag. At least the beer was cheap. Theatre of the Absurd from the Romanian-born playwright with a great name. By selecting Ionesco for university studies I found a fine way to justify engagement with nonsense.

In this capriciously named play, the Absurdist literary movement lends philosophical respectability to dialogue and interaction that is radically Pythonesque. Ionesco’s plays are deliberately ridiculous because his intention is serious. His creations arise from a distrust of language and the world that it projects. In Tueur Sans Gages, Bérenger’s long speech to dissuade the killer from killing, appealing to idealism and moral codes, is shown to be futile. In the post-war context of Rhinocéros, the central plot that citizens of a small French town turn into rhinoceroses parallels the disbelief that such normal people might become fascists/Nazis. Ionesco’s search was for the absolute, for a paradise on earth that he once glimpsed as a child and could never forget. “What I find most abnormal is the normal, the banal,” he said. “All existence seems unbelievable, beginning with my own.” My kind of French literature.

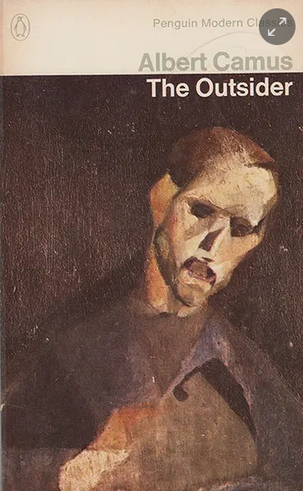

After battling through classical French plays by Corneille and Racine and pretending to have read the prolific output of Balzac and Zola, we undergraduates were allowed to venture into more modern territory. With Camus and “L´Étranger” — “The Outsider” in the British translation — I was on home ground. Here was an archetypal alienated man in a work that denied all traditional religious and secular belief systems and set out a vision of existence as absurd. The French made of l’Absurde a bona fide philosophical movement, while we went one better by having The Cure singing the song. Meursault is condemned for not being what society expects, or at least making an outward pretence of it. Camus’s antihero is no intellectual, no tortured soul. He doesn’t care much one way or the other about anything. He is incurious, unquestioning, undemanding. Indifferent to his life. The given moment is his only context and he responds to its stimuli: such simple carnal pleasures as warmth, swimming, sex, smoking. Stripped of philosophy, religion and other theoretical fabrications, Camus is saying, this is what remains: the human animal in its habitat. In his novel, Meursault’s ultimate crime will be not the murder of an innocent man, but failing to show emotion at his mother’s funeral and thereby observe the etiquette of contemporary mores; his death sentence will be passed because “he doesn't play the game,” doesn’t make a public display of grief that he does not feel at the time. Anyone who has passed through profound grief will, if they are as candid as Camus’s protagonist, knows that there is nothing pure about it. Mixed into the pain of loss are so-called “inappropriate” feelings of relief, happiness, meanness and the like, contributing to a maelstrom of emotion — and that is what grief is, and what makes it so hard to bear. Meursault has no reason to lie about it, just as he has no ambition or other drive. That doesn’t mean that he is unfeeling, simply that he may not consciously process feeling like you or I. When he pulls the trigger on the beach, he feels oppressed by the sun’s blinding light and heat, making the veins in his forehead throb, much as he reacted at his mother’s burial. When the judge asks him why he killed the Arab, he says: “Because of the sun.” Meursault’s honesty in authenticity, showing up the hypocrisy of conventional society, is what vindicates him in the end and gives him peace in the face of his imminent execution. Suddenly, I was at university. It was 1978 and I was free. Sort of. There were all these books to be read in French and German. Prévost’s tedious Manon Lescault and La Double Inconstance by Marivaux: s’il vous plaît... I was interested in the human condition, not this staid tosh. It might have been A Thing in its day but its day had been and gone. Unfortunately, they were required reading, so I couldn’t escape them altogether, but even in the days before Artificial Intelligence one could still use one’s nous and cobble together some acceptable nonsense as an essay.

As an item of light relief, along came Candide, an entertaining 18th century romp and a welcome reminder that one of the best critiques of unsound philosophy is irony. You only have to look at a portrait of Voltaire to know how much fun the grand old atheist and republican had with his advocacy. This kind of fun, as we know, is a serious matter, and Voltaire’s satires and warnings as a champion of reason remain a safeguard against the divisiveness of religious intolerance, political dogmatism, unfounded conspiracy theories and other persuasions of fear. “Ceux qui peuvent vous faire croire à des absurdités peuvent vous faire commettre des atrocités.” My angst-ridden teens found articulation in Laing’s humane yet deeply disturbing rewriting of schizophrenia, which he saw as originating in intolerable family dynamics. The disassociated self that he described was experienced as fake, a sham, depersonalized, devalued, a tortured, isolated being unable to make contact with a world that was no longer real. I don’t know how adolescence felt to my contemporaries, but I sure as hell had my own “double binds” that undid me and threatened my sanity.

Like anti-psychiatry’s David Cooper, Laing’s compassionate approach posited schizoid disorder as the sensitive soul’s desperate attempt to preserve itself against undermining persecution by cruel or dishonest others, or even the reaction of a healthy mind to a mad world. They both rejected the use of chemical medication and electroshock treatment on sufferers and rather than seeing the psychopathological condition as a problem, suggested that it was valid. The romanticized vision of the madman was irresistible to the traumatized teenage me. Laing quoted passages from Dostoyevsky and Jean Genet to illustrate his thesis, artistic authorities that for me trumped the narrowly scientific, and I saw myself, if not quite in the company of broken anti-heroes, at least no longer alone. Cooper took things a step further, presenting the language of madness as that of poetic truth which breaks in through the cracks. The disturbed individual, however, wants relief of their torment, not congratulation. I can’t help feeling that that many of the patients of this school would have benefited immensely from a dose or two of the right drug. I do know that my will to understand the human condition inclined me away from psychology, which I saw as unequal to the task, being strictly limited in its analytical discipline, and towards the study of literature, where I hoped to gain insight from poetic minds (and, hey, have some fun), and so the books kept coming. The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum [1974] is a story of character assassination by the sensationalist media. I have a favourable memory of the novel because I mumbled about it in rubbish German at a university interview in 1978 and they still let me in.

I wonder how Böll would write it today if he knew that the Bildzeitung was going to replace editorial positions with AI? A breakthrough moment for the 17-year-old me was being able to read an entire, if slim, book in German. We were led through it patiently and ably and at just the right pace by our teacher, Barry Chacksfield, at Solihull School.

It was a good choice for us students. The central character was a youngster like us and the narrative was presented in easy-to-digest chunks. It was also gave a glimpse of internal German opposition to the Nazi regime in the late 1930s. I remember liking the symbolism of the “Lesender Klosterschüler” carving: reading as a political act of resistance. Mostly, I sympathized with the boy’s third and definitive reason for wanting to escape from his home town of Rerik: “Weil Sansibar da ist”: because Zanzibar exists. |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed