|

I read this book as one teenager amongst others at an age when we were adopting value systems of social correctness, while the reality we experienced at school was the law of the jungle. The metaphor of the struggle between principled behaviour and unfettered brutality is as old as human civilization, but no one feels it more strongly than an adolescent.

0 Comments

Despite being set the book to read as a school text — virtually guaranteed to put you off any book at all — a story in which malevolent children developed a power rivalling that of adults was always going to catch a youngster’s attention.

Aliens assuming the form of ordinary girls and boys with weird telepathic and telekinetic abilities was fascinating and deeply unsettling. I didn’t know it at the time, but a love affair with the powerfully imaginative storytelling we call science fiction and fantasy was just beginning. Huge alien tripods marching over England! Laying waste to Woking, which seemed to indicate a dastardly intelligence at work. I was a fervent fan of Doctor Who on TV, but this was my first taste of science fiction in print.

I was maybe eleven and this was the longest book I had ever read, very different for being non-fiction, and an inspiration for a lad who found himself a real hero rather than a comic book one.

Much later, I would learn of Bader’s deplorable and openly professed views on race. He truly was a bigot of the worst kind, what we would nowadays call a white supremacist. There was not a hint of this in Brickhill’s exciting biography, complete with photographs, which told the story of an unconventional character, plucky in the extreme, cheery in the face of every adversity, flying Spitfires and Hurricanes in combat against the Luftwaffe despite having both legs amputated, a pilot ace decorated with highest honours, shot down and escaping capture at one point by knotting together sheets and climbing out of a hospital window, before being sent to Colditz. I badly wanted a hero to admire and here was a man whom even the Germans respected. Today, I wonder if their mutual respect wasn’t based on not so very different ideologies. I am glad I didn’t know at the time. A boy shouldn’t have all his dreams taken away. With his confident smile and pipe, Bader looked avuncular in the black-and-white photos, not dissimilar in appearance to my Uncle Bill, who also fought in the Second World War and later had his own legs disabled by a mining accident. I am featuring a book that I never read. I wanted to as a boy, but I had the strong impression that it wasn’t allowed. It sat on my sister’s bookshelf and I wasn’t bold enough to take those books. So I effectively censored it from myself. I certainly wouldn’t recommend Iron Pirate as it is dreadfully turgid, old-fashioned Boy’s Own drivel. But no book should be banned by prejudice or fear.

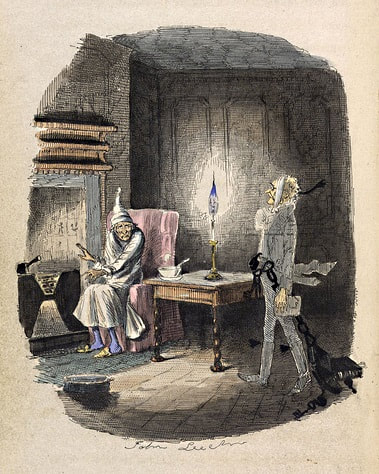

The self-reliant castaway was more than a brave hero for me: he was more or less what I wanted to be. As a boy, I used to have a recurring dream of being the only person in a vast, deserted city. Far from being afraid or lonely, I was intrigued and excited to have a world without end to myself to explore and discover. I was quite a loner, so maybe the dream sought a way of turning childhood solitude into a power — or maybe I just wanted a portal to freedom and adventure. Something you can spend a whole life looking for before realizing you had it all along. Crusoe represented the same principle in the natural setting of an island. I felt somehow vindicated by the championing of a solitary man’s resilience and the message that you could win out by going it alone. It was TV again that brought home the lonely, thrilling enchantment with stark and simple storylines of one man’s resourcefulness and the most haunting theme tune ever composed. It was the grimness and sheer enormity of 19th century London that beguiled me in Dickens.

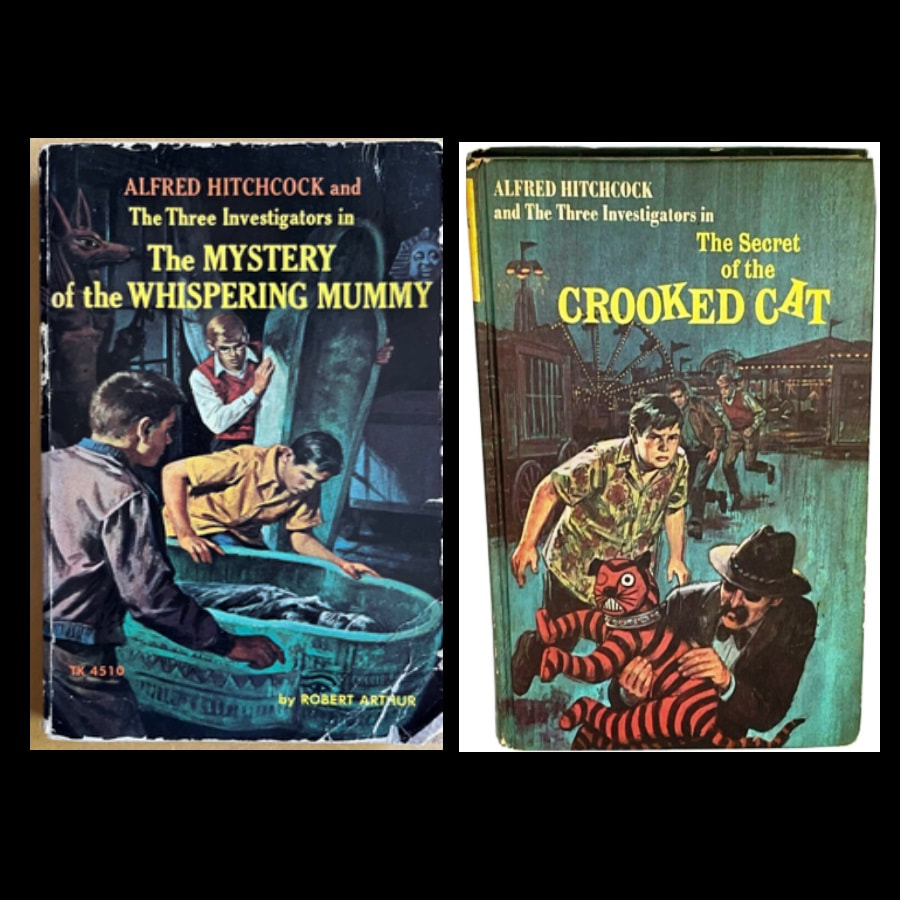

In his best-loved novella, meanness, cold and snow are overcome with goodwill and a message of warm hope. Who doesn’t need that? Moving on from the Famous Five, I discovered another series about young sleuths, older boys this time and more focussed, solving mysteries with a combination of daring and brainwork, and getting the better of adult baddies. Fictional friends that I could imagine collaborating with and feel that urgent earnestness of boyhood.

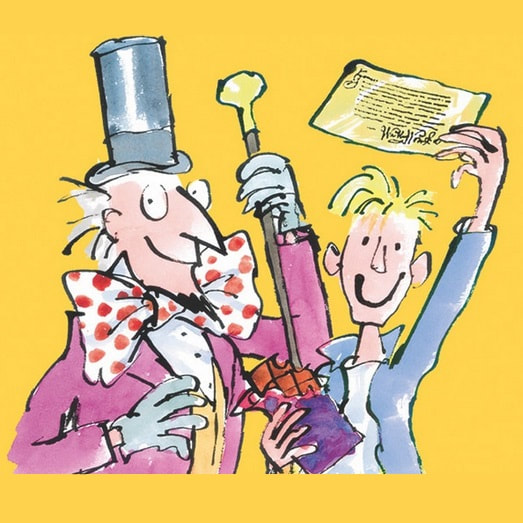

Although The Three Investigators series was presented by Alfred Hitchcock, he didn’t write any of them. The Mystery of the Whispering Mummy was by lead author, Robert Arthur Jr., while The Secret of the Crooked Cat was by William Arden. More Dahl, and this time a children’s classic that I didn’t read until I was in my thirties. The Twits are so superbly beastly to each other. In another happy marriage of author with illustrator, Quentin Blake gives us some unforgettable images. “A person who has good thoughts cannot ever be ugly. You can have a wonky nose and a crooked mouth and a double chin and stick-out teeth, but if you have good thoughts they will shine out of your face like sunbeams and you will always look lovely.” “If a person has ugly thoughts, it begins to show on the face. And when that person has ugly thoughts every day, every week, every year, the face gets uglier and uglier until you can hardly bear to look at it.”

Another story that I didn’t read but was read: by Bernard Cribbins on BBC1’s Jackanory in 1968, just before Blue Peter.

Here was a world of wonder in which Golden Tickets were possible and horrible children succumbed to equally horrible fates. And all that chocolate! Jackanory narrated me classics I might never have read myself: Brer Rabbit, The Snow Queen, Rudyard Kipling’s Just So stories, Japanese, Indian & Greek tales, Worzel Gummidge... Dahl’s widow said that Charlie was originally written as “a little black boy” and the change to a white character was driven by Dahl's agent, who thought a black Charlie would not appeal to readers. Commercially, lamentably, the agent was right. Like other white British kids back then, I was so conditioned to believe that black people were not like “us” that I wouldn’t have identified with a coloured Charlie — and it was the white population, of course, who overwhelmingly dominated English-speaking society, its spending power and the market for books. |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed