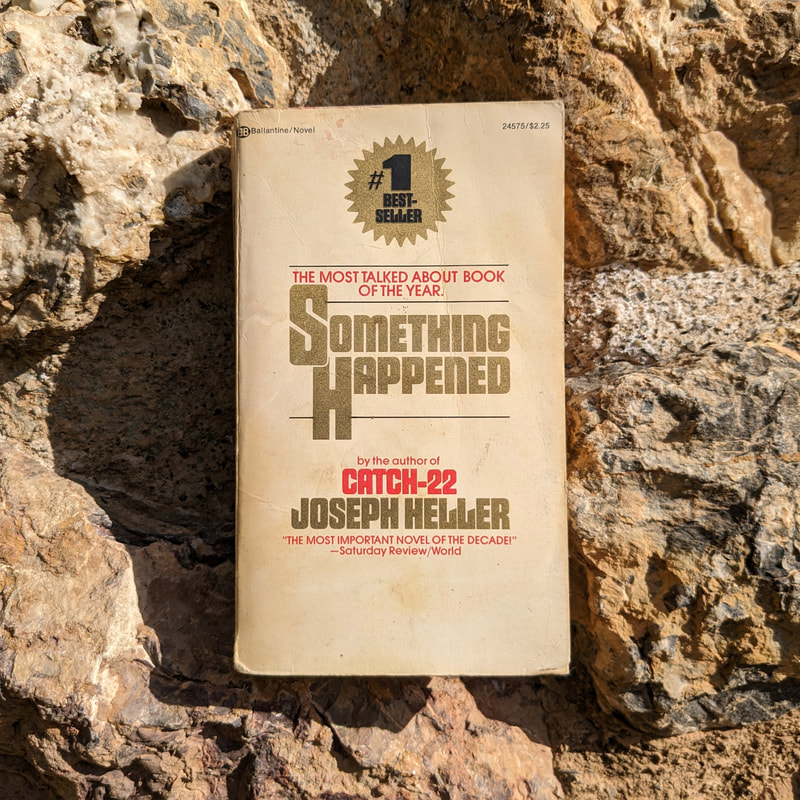

Little known beside Heller’s Catch-22, this powerful read is a far more impressive achievement.

The monologue of a middle-class American man exerts a mesmeric effect on the reader. Bob Slocum details his self-incriminating thoughts, desires and misdemeanours, and holds back nothing. He offers nothing to exonerate the uncharitability of his nature; there is nothing to be admired in his life, whether home, office, or extra-marital, and he knows it. And it is this unembellished honesty that is the strength of the book. He says what he truly feels, not what he is supposed to feel. One can hear Heller thinking: “hypocrite lecteur!--mon semblable,— mon frère!” When Heller makes Slocum misogynistic, misanthropic, sexist, racist, he is saying: there is your typical American male. Representative of his culture and times. Any pretence is foregone. He has three children, a girl and two boys. One of the boys, Derek, is brain-damaged to the point of being a lifelong burden on the family. Bob Slocum tells us how he no longer loves the retarded kid and how they would be better off without him. It is awful. And it is something—is it not?— that might go through the head of any parent in that grotesque situation. The monologue’s confessional style has such unadulterated candour that when one truth is not enough, another is added within parentheses. It is very effective. It’s not just Bob Slocum who’s unhappy: there’s no one who is. Heller shows us the shallowness of conventional, consumerist, American society in all its sad idiocy. Slocum is tormented by the loss of himself, or the child he remembers being, or hopes existed and is not an illusion, “a deserted little boy I know who will never grow older and never change”. “I can’t help him. Between us now there is a cavernous void. He is always nearby.” “I know at last what I want to be when I grow up. When I grow up I want to be a little boy.” This identity becomes at times confused or conflated with his son, who is nine. In the end, and not until the end, we learn that, yes, “something happened.” And it is so ambiguously related that it shocks to the core. This it is that explains Slocum’s compulsion to unadulterated confessional. It wouldn’t have changed the man he is but he might not have felt the need to tell us. It is not pride in his perspicacity or self-knowledge but suppressed panic that drives him. “I’ve got anxiety; I suppress hysteria.” He applies himself at work for the first time and loses himself in it. Taking heed of what his son’s gym teacher told the boy: that it’s “time to start learning some responsibility and discipline.” He will also put this account together and you will get everything.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed