|

The two narrative voices are of Phil Dick himself as a true-to-life character, and of his fictional friend, Nicholas Brady, who is in fact Dick’s alter ego.

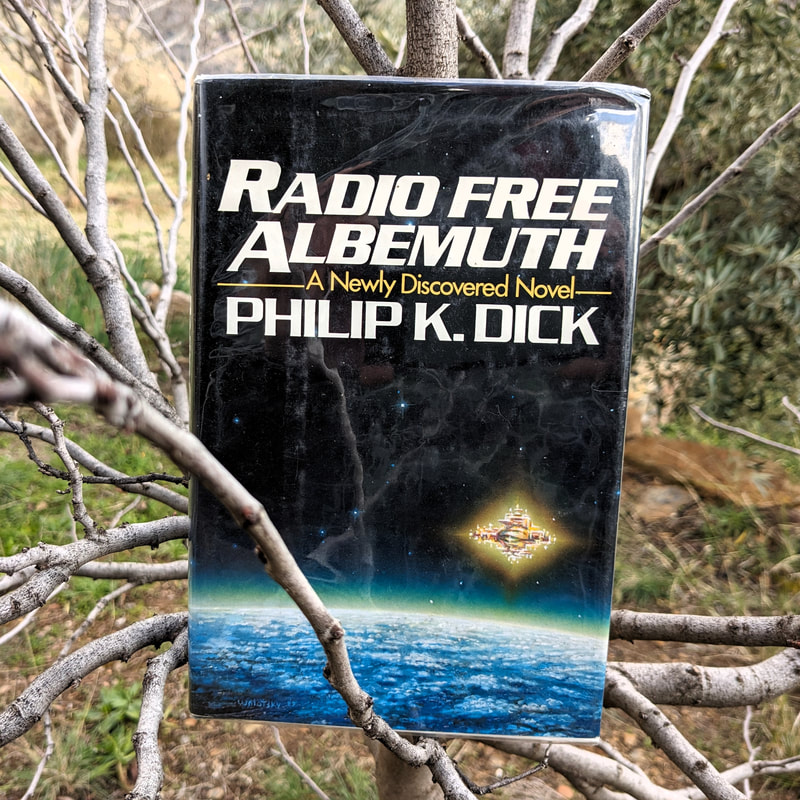

We have a US president, supported by Russia, who is dictatorial, ruthless and a threat to his own people and democracy. Freemont embodies authoritarian hostility to freethinking, empathy and charity. “The Soviets backed him, the right-wingers backed him…” President Fremont was modelled on Nixon. I’m not sure that even Philip K. Dick would have dredged up the monstrosity that is Trump from the pit of his imagining. Brady’s experience of receiving extraterrestrial transmissions via condensed information-rich beams of pink, phosphene light is no less than Dick’s in real life: which he knows is a lot to take at face value! And so, by the device of making himself a character in the book, he seeks to take us along with him from scepticism to the realization of belief. The shift in his viewpoint as the story progresses makes it a delightful ploy. “… although I was a professional science fiction writer, I could not really give credence to the idea that an extraterrestrial intelligence from another star system was communicating with him; I never took such notions seriously… Nicholas, I decided, had begun to part company with reality… This was a classic example of how the human mind, lacking real solutions, managed its miseries.” Dick’s, then, is the voice of reason. His fiction is just that, he makes clear. As Brady says, “Your books are so—well, they’re nuts.” Until the denouement, the easy mood and self-deprecatory vein lend the narrative a certain charisma, and that it lacks the madcap scheming and complexity found in other works by Philip K. Dick helps to make Radio Free Albemuth a neatly balanced read. A lightheartedness comes across in such comments as “the US intelligence community, as they like to call themselves.” When the iron hand of the evil empire does strike, its savagery is shockingly efficient and effortless, almost casual. The ease with which the light of civilization can go out is the warning of this novel. Phil’s (the character’s) reasonable take on things, his sensible rationale and healthy scepticism, which the reader naturally goes along with, will be won over by evidence and events and, ultimately, by incontrovertible violence. Along the way, Dick shares deeply personal insights and the story acquires depth in his treatment of VALIS and divinity, perception and illusion, the nature of time, the meaning of the Orphic mysteries—and acquires urgency, since their lives are at stake. Set against Fremont’s tyranny is a force that anyone with an insular view of science fiction may find surprising, because it is love. That is what Brady experienced VALIS to be: the Vast Active Living Intelligence System that for him (and Dick) was synonymous with God. A vital theme in the novel is awakening, or anamnesis. Waking up to our true nature as well as to the baleful threat of the adversary, which all too easily wins out. Its oppressive power is great and, indeed, “the darkness closed over us completely.” It is happening again and always. [The image is a 1985 first edition]

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Blogging good books

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed