In recent years, Non-Governmental Organizations have multiplied and spread all over the globe. If many are praised as humanitarian saviours, severe criticism of others has been leading to a major self-reassessment. This structural appraisal of the changing world of NGOs discovers a new model of NGO in the making: the network.

NGO 2.0: the next generation in civil society

|

Who do they represent and where do they get their mandate from? It is a difficult question to answer if you open the closet of today's NGOs. Not only have they abandoned the lofty ideals of fighting injustices, impunity, corruption, etc, but they are themselves party to these vices.

Robert Wundeh Eno, Cameroonian in The Gambia BBC debate: NGOs: achievers or deceivers? 20 Feb 2004 In an unprecedented step, international civil society organisations have come together to demonstrate their commitment to transparency and accountability. Amnesty International News on the signing of the Accountability Charter 6 June 2006 |

They can be as militant and high-profile as Greenpeace, or as lowly and unknown as the Chembe AIDS project in Malawi.

Oxfam, Medecins Sans Frontières, the World Wildlife Fund, Amnesty International — and a small group of women in Bangladesh supporting each other’s one-person textile businesses with small loans and advice: they are all NGOs. The large Northern-based organizations, and the small self-help community based in the South, all fit the definition of a Non-Governmental Organization. The World Bank, itself an IGO or intergovernmental organization, describes NGOs as: "private organizations that pursue activities to relieve suffering, promote the interests of the poor, protect the environment, provide basic social services, or undertake community development." For the United Nations an NGO is “a not-for-profit, voluntary citizens’ group, which is organized on a local, national or international level to address issues in support of the public good.”

NGOs are commonly understood to follow an essentially altruistic mission, striving to work for the underprivileged or persecuted, and often in circumstances where officially elected bodies fail to do so. To understand the criticisms levelled against them, especially of late, we might ask:

Who, in these private organizations, decides what is good for the public?

Where are NGOs going wrong?

NGOs have traditionally acted as intermediaries between donors and beneficiaries. Janet Townsend, author of works on development NGOs and Board Member of International NGO Training and Research Centre INTRAC, sees a fundamental flaw right here. In an interview with Myriades1 magazine, she pointed out how the traditional structural hierarchy places donors at the top, with the NGOs in the middle performing their bidding of their fund-providers, and beneficiaries at the bottom as the humble recipients. “The most serious failing of NGOs,” said Townsend, “is that they are middle-class institutions with accountability to donors.” The typical donor lives in a world in which money is invested in business and a prompt return is expected on that investment. They like to see visible, short-term results from their charitable donations also. This can lead Northern-based NGOs —often seen as the protagonists on the international stage in the relief of suffering— to confuse protagonism with the real objectives: and then the organizations lose their way. While they may be organizing and distributing assistance in the form of equipment, materials, human resources or emergency aid, it may not necessarily be what the beneficiaries want or need.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Africa agrees. Commenting on a report on Africa’s Sahel region published this month by prominent international NGOs including Oxfam, the British Red Cross, CARE International and Save the Children, it highlights the discrepancy between “the fact that donors and aid agencies recognise that the problems of the Sahel are long-term while most projects are only funded for one or two years (…) Donors require results after every year, even if that is not realistic (…)

The report says that donor pressure means aid agencies focus too much on measuring the production of heavy, nutrient-scarce staples like millet and sorghum.” These food stuffs fail to provide a balanced diet and can thus accentuate malnutrition, instead of alleviating it. “‘[Aid projects in the Sahel] are almost always driven by externally imposed ideas for development’ and the majority of aid organisations develop their programmes ‘on the basis of their own priorities and their own visions’ the report says. When designing aid projects the views of locals are usually ignored because they are ‘unpredictable’. Once projects are set up, aid agencies often manage them in ‘narrow and inflexible ways’ that are focused more on looking good to donors than measuring real improvements to people’s lives.”

“In particular,” says the United Nations’ specialized agency, the International Labour Organization, “NGOs are accused of being economically and ideologically controlled by Western donors whose funds are conditional on the NGOs not seriously challenging the status quo; of being politically unaccountable to the local populace and solely accountable to external donors.”

The extent to which NGOs can be fund-driven was illustrated by their publicity campaigns on TV and in the press in the 1980s, when the competition for limited donor funds demonstrated a level of ruthlessness that had to be censured by their peers. To curb the emotive, distressing images —of starving and dying children— published by NGOs vying in the media for contributions, the General Assembly of European NGOs in 1989 felt obliged to draw up a “Code of Conduct on Images and Messages relating to the Third World”.

Janet Townsend, exemplified the damage that NGOs with a Western-controlled, vertical hierarchy can do. “In India, the World Bank set up organizations among local people to act as markets. But instead of marketing their own produce, the people were selling imported goods or goods made in India by multi-nationals.” Here we see, she says, NGOs being manipulated as “a specific arm of capitalism: making people governable.” Donated food aid can even do more harm than good, and end up “under-cutting local producers and hence have a negative effect on local farmers and the economy.” It keeps people dependent and prevents the development of self-reliance. The political pressure on NGOs can be very real: “NGOs must obtain the best results and better promote United States’ foreign policy objectives or we’ll find new partners.” (Andrew Natsios, Director of USAID, the United States' State Department Agency for Development Assistance May 21, 2003).

A cautionary tale

The traditional NGO structure, answerable to donors and with a management recruited from donor-countries, is nonetheless typical. The major aid agencies are organized with this hierarchy. Is such a power-structure necessarily pernicious? Here we need to consult professionals who have seen the consequences at first hand.

The Chembe AIDS Project, a tiny NGO in a fishing village on Lake Nyasa, Malawi, represents NGOs at the micro-scale. In 1996, Irit Rabinvich was on vacation from Israel in Chembe when she became aware of how ignorance about AIDS was spreading the disease and destroying families. With the help of a few volunteers and individual donors, Irit would eventually send 200 local teenagers to school, teach women about the HIV virus and their rights as citizens, and create a vital vegetable-growing business with women who had been prostituting themselves to feed their children. And yet their funds were negligible. So when a “very big, very well-known” charity offered food aid to hungry Chembe, it came as a relief.

And yet, to Rabinvich’s astonishment, the village women soon came to ask her to send the large NGO’s food away. It had been channelling the free food through a school, unaware that the teachers were demanding money for it. Mothers of children who had no money to pay for the food were told they would have to have sex with the teachers. Irit Rabinvich explains that when she complained to the world-renowned NGO, it did nothing. Their representative “didn’t even get out of the big car, to not get dirty,” she said. The organization later told Irit to stop protesting, as it was “bad for their reports.”

Rather than listen to the beneficiaries, the NGO officers were under pressure to present flattering reports to higher-ups in the hierarchy --- those who controlled the funding --- who could subsequently present the work of the NGO in good light to donors. In other words, the way the NGO was structured meant that it ended up being more concerned with its own organization than the people in need.

Oxfam, Medecins Sans Frontières, the World Wildlife Fund, Amnesty International — and a small group of women in Bangladesh supporting each other’s one-person textile businesses with small loans and advice: they are all NGOs. The large Northern-based organizations, and the small self-help community based in the South, all fit the definition of a Non-Governmental Organization. The World Bank, itself an IGO or intergovernmental organization, describes NGOs as: "private organizations that pursue activities to relieve suffering, promote the interests of the poor, protect the environment, provide basic social services, or undertake community development." For the United Nations an NGO is “a not-for-profit, voluntary citizens’ group, which is organized on a local, national or international level to address issues in support of the public good.”

NGOs are commonly understood to follow an essentially altruistic mission, striving to work for the underprivileged or persecuted, and often in circumstances where officially elected bodies fail to do so. To understand the criticisms levelled against them, especially of late, we might ask:

Who, in these private organizations, decides what is good for the public?

Where are NGOs going wrong?

NGOs have traditionally acted as intermediaries between donors and beneficiaries. Janet Townsend, author of works on development NGOs and Board Member of International NGO Training and Research Centre INTRAC, sees a fundamental flaw right here. In an interview with Myriades1 magazine, she pointed out how the traditional structural hierarchy places donors at the top, with the NGOs in the middle performing their bidding of their fund-providers, and beneficiaries at the bottom as the humble recipients. “The most serious failing of NGOs,” said Townsend, “is that they are middle-class institutions with accountability to donors.” The typical donor lives in a world in which money is invested in business and a prompt return is expected on that investment. They like to see visible, short-term results from their charitable donations also. This can lead Northern-based NGOs —often seen as the protagonists on the international stage in the relief of suffering— to confuse protagonism with the real objectives: and then the organizations lose their way. While they may be organizing and distributing assistance in the form of equipment, materials, human resources or emergency aid, it may not necessarily be what the beneficiaries want or need.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Africa agrees. Commenting on a report on Africa’s Sahel region published this month by prominent international NGOs including Oxfam, the British Red Cross, CARE International and Save the Children, it highlights the discrepancy between “the fact that donors and aid agencies recognise that the problems of the Sahel are long-term while most projects are only funded for one or two years (…) Donors require results after every year, even if that is not realistic (…)

The report says that donor pressure means aid agencies focus too much on measuring the production of heavy, nutrient-scarce staples like millet and sorghum.” These food stuffs fail to provide a balanced diet and can thus accentuate malnutrition, instead of alleviating it. “‘[Aid projects in the Sahel] are almost always driven by externally imposed ideas for development’ and the majority of aid organisations develop their programmes ‘on the basis of their own priorities and their own visions’ the report says. When designing aid projects the views of locals are usually ignored because they are ‘unpredictable’. Once projects are set up, aid agencies often manage them in ‘narrow and inflexible ways’ that are focused more on looking good to donors than measuring real improvements to people’s lives.”

“In particular,” says the United Nations’ specialized agency, the International Labour Organization, “NGOs are accused of being economically and ideologically controlled by Western donors whose funds are conditional on the NGOs not seriously challenging the status quo; of being politically unaccountable to the local populace and solely accountable to external donors.”

The extent to which NGOs can be fund-driven was illustrated by their publicity campaigns on TV and in the press in the 1980s, when the competition for limited donor funds demonstrated a level of ruthlessness that had to be censured by their peers. To curb the emotive, distressing images —of starving and dying children— published by NGOs vying in the media for contributions, the General Assembly of European NGOs in 1989 felt obliged to draw up a “Code of Conduct on Images and Messages relating to the Third World”.

Janet Townsend, exemplified the damage that NGOs with a Western-controlled, vertical hierarchy can do. “In India, the World Bank set up organizations among local people to act as markets. But instead of marketing their own produce, the people were selling imported goods or goods made in India by multi-nationals.” Here we see, she says, NGOs being manipulated as “a specific arm of capitalism: making people governable.” Donated food aid can even do more harm than good, and end up “under-cutting local producers and hence have a negative effect on local farmers and the economy.” It keeps people dependent and prevents the development of self-reliance. The political pressure on NGOs can be very real: “NGOs must obtain the best results and better promote United States’ foreign policy objectives or we’ll find new partners.” (Andrew Natsios, Director of USAID, the United States' State Department Agency for Development Assistance May 21, 2003).

A cautionary tale

The traditional NGO structure, answerable to donors and with a management recruited from donor-countries, is nonetheless typical. The major aid agencies are organized with this hierarchy. Is such a power-structure necessarily pernicious? Here we need to consult professionals who have seen the consequences at first hand.

The Chembe AIDS Project, a tiny NGO in a fishing village on Lake Nyasa, Malawi, represents NGOs at the micro-scale. In 1996, Irit Rabinvich was on vacation from Israel in Chembe when she became aware of how ignorance about AIDS was spreading the disease and destroying families. With the help of a few volunteers and individual donors, Irit would eventually send 200 local teenagers to school, teach women about the HIV virus and their rights as citizens, and create a vital vegetable-growing business with women who had been prostituting themselves to feed their children. And yet their funds were negligible. So when a “very big, very well-known” charity offered food aid to hungry Chembe, it came as a relief.

And yet, to Rabinvich’s astonishment, the village women soon came to ask her to send the large NGO’s food away. It had been channelling the free food through a school, unaware that the teachers were demanding money for it. Mothers of children who had no money to pay for the food were told they would have to have sex with the teachers. Irit Rabinvich explains that when she complained to the world-renowned NGO, it did nothing. Their representative “didn’t even get out of the big car, to not get dirty,” she said. The organization later told Irit to stop protesting, as it was “bad for their reports.”

Rather than listen to the beneficiaries, the NGO officers were under pressure to present flattering reports to higher-ups in the hierarchy --- those who controlled the funding --- who could subsequently present the work of the NGO in good light to donors. In other words, the way the NGO was structured meant that it ended up being more concerned with its own organization than the people in need.

|

Learning from experience

The experience of many aid workers is distilled in networklearningorg’s educational website that teaches “How to build a good small NGO.” The negligent failure to consult with local people, imposing instead imported ideas, is a common theme in their training models. |

“An NGO in Asia,” they offer by way of illustration, “was trying to help families on the edge of survival. Most of their energy went into providing a school. The children came out of the school able to read, but not equipped to earn an income. The families stayed poor. If the NGO had adopted the strategy ‘To ensure that one member of each family can earn a living’ they might have made better progress.”

Taking another case, that of orphans, they advise that: “Traditionally in Africa, orphans were accommodated by the extended family. But in Europe people built orphanages. People seem to love building orphanages. The idea makes a nice mental picture — the saintly founders, surrounded by the loving children who are only alive because of them, all in a building that is a concrete proof of their benevolence. But this picture is about the egos of the builders, not what is best for children. Today, AIDS has brought a large number of orphans. How should they be cared for? The money that can build an orphanage can also be spent on fostering the babies with their grannies and paying an allowance. If there are no grannies, aunties or big sisters, they can be fostered with non-related families.”

Often the building of a dam causes untold disruption and displacement of peoples. Western NGOs tend automatically to oppose such projects, but there is no “one size fits all” strategy. When western NGOs halted the construction of a dam in Uganda, Sebastian Mallaby, author of “The World’s Banker” talked to the locals: “We interviewed villager after villager — and found the same story. The dam people had come and promised generous financial terms, and the villagers were happy to accept them and relocate.” Mallaby called it “a tragedy for Uganda, since millions of Ugandans are being deprived of electricity (…) And a tragedy for the antipoverty fight worldwide, since projects in dozens of countries are being held up for fear of activist resistance.”

This lack of awareness of local wants and needs can also express itself in insensitivity to the local “target” culture, especially when an NGO has a conflicting religious ideology. Speaking of Cambodia, Miriam Mulsow, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Texas Tech University, says: “When an NGO goes into an area, the assumption always exists that NGOs are going to try to convert people to Christianity, and in many cases this is what happens. So, a lot of resistance is encountered in working with the NGOs at first, because most of the people there are Buddhist and they are happy with their current beliefs.”

What makes for a good operational NGO?

For Janet Townsend, accountability to beneficiaries is key. When beneficiaries are represented on the local board of the NGO, they have a voice and vote in what work is carried out and how. Townsend cites the Indian RASS as an example of this democratization of the internal NGO network. RASS started out with what she described as a “paternalistic” hierarchy. The involvement of the women beneficiaries in the organization “changed that structure considerably” and led to the women becoming paid employees managing the NGO at local levels.

The importance of involving local people in the consultative process and running of NGOs is underlined by the professional operators on the ground: it is in this way that inappropriate strategies can be avoided. The model suggested by Townsend corresponds to that advocated by networklearning.org: “Most groups of beneficiaries can play an active part in the process of finding out what the problems are. Children over seven, people with psychiatric problems, even people with special education needs may still be able to communicate. If you say to them in a careful and respectful way, “What are your problems?”; “What kind of place do you want to live in and why?” they will have a point of view worth hearing.” They quote an Ethiopian government officer, after attending a needs assessment workshop with older people, as saying: “I never believed these poor older people had anything to say. Now I have changed my mind and will always consult them.”

Townsend stressed how crucial it is to have “beneficiaries on the board” that directs the local operation. Networktraining.org says: “If the membership is right, it will truly represent the interests of the beneficiaries and a bridge is built between the NGO and the wider community.”

Irit Rabinvich emphasized that her programme with the village women in Chembe worked at its best when the women themselves were consulted. She held meetings with the local women and it was their own proposal that was finally adopted: they chose to not simply receive but to work for the limited food that Chembe Aids Project could provide. In return for porridge, they repaired roads, made a school building, cleaned the graveyard. It gave them a stake in the project and dignity.

The International Non-Governmental Organisations Accountability Charter is a major step forward in this direction. It includes a pledge to consult with beneficiaries among a number of other self-regulatory and ethical principles. Eleven leading aid agencies have committed to it, including ActionAid International, Amnesty International, CIVICUS World Alliance for Citizen Participation, Consumers International, Greenpeace International, Oxfam International and International Save the Children Alliance. Others, such as Medecins Sans Frontières, have long been following this philosophy. The Charter’s vision of accountability is inclusive and involves all the stakeholders: donors, beneficiaries, the NGO itself, partner organizations and governments and “ecosystems, which cannot speak for or defend themselves.” INGO Accountability Charter.

Meaningful networks

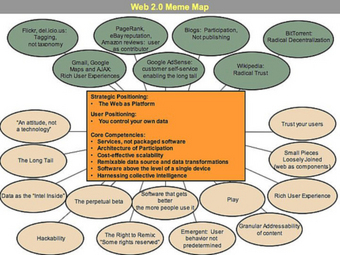

For NGOs to evolve towards a model of genuine reciprocity, however, the challenge now is to incorporate this democracy into the structure of the organizations themselves: making them into meaningful networks. Irit Rabinvich and Janet Townsend’s experiences show that another model is possible: a genuine network that actively involves all the people concerned. As a paradigm it is strikingly mirrored in the changing reality of the Internet. Web 2.0 was coined by O’Reilly Media in 2003 to refer to the new generation in the Internet.

Taking another case, that of orphans, they advise that: “Traditionally in Africa, orphans were accommodated by the extended family. But in Europe people built orphanages. People seem to love building orphanages. The idea makes a nice mental picture — the saintly founders, surrounded by the loving children who are only alive because of them, all in a building that is a concrete proof of their benevolence. But this picture is about the egos of the builders, not what is best for children. Today, AIDS has brought a large number of orphans. How should they be cared for? The money that can build an orphanage can also be spent on fostering the babies with their grannies and paying an allowance. If there are no grannies, aunties or big sisters, they can be fostered with non-related families.”

Often the building of a dam causes untold disruption and displacement of peoples. Western NGOs tend automatically to oppose such projects, but there is no “one size fits all” strategy. When western NGOs halted the construction of a dam in Uganda, Sebastian Mallaby, author of “The World’s Banker” talked to the locals: “We interviewed villager after villager — and found the same story. The dam people had come and promised generous financial terms, and the villagers were happy to accept them and relocate.” Mallaby called it “a tragedy for Uganda, since millions of Ugandans are being deprived of electricity (…) And a tragedy for the antipoverty fight worldwide, since projects in dozens of countries are being held up for fear of activist resistance.”

This lack of awareness of local wants and needs can also express itself in insensitivity to the local “target” culture, especially when an NGO has a conflicting religious ideology. Speaking of Cambodia, Miriam Mulsow, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Texas Tech University, says: “When an NGO goes into an area, the assumption always exists that NGOs are going to try to convert people to Christianity, and in many cases this is what happens. So, a lot of resistance is encountered in working with the NGOs at first, because most of the people there are Buddhist and they are happy with their current beliefs.”

What makes for a good operational NGO?

For Janet Townsend, accountability to beneficiaries is key. When beneficiaries are represented on the local board of the NGO, they have a voice and vote in what work is carried out and how. Townsend cites the Indian RASS as an example of this democratization of the internal NGO network. RASS started out with what she described as a “paternalistic” hierarchy. The involvement of the women beneficiaries in the organization “changed that structure considerably” and led to the women becoming paid employees managing the NGO at local levels.

The importance of involving local people in the consultative process and running of NGOs is underlined by the professional operators on the ground: it is in this way that inappropriate strategies can be avoided. The model suggested by Townsend corresponds to that advocated by networklearning.org: “Most groups of beneficiaries can play an active part in the process of finding out what the problems are. Children over seven, people with psychiatric problems, even people with special education needs may still be able to communicate. If you say to them in a careful and respectful way, “What are your problems?”; “What kind of place do you want to live in and why?” they will have a point of view worth hearing.” They quote an Ethiopian government officer, after attending a needs assessment workshop with older people, as saying: “I never believed these poor older people had anything to say. Now I have changed my mind and will always consult them.”

Townsend stressed how crucial it is to have “beneficiaries on the board” that directs the local operation. Networktraining.org says: “If the membership is right, it will truly represent the interests of the beneficiaries and a bridge is built between the NGO and the wider community.”

Irit Rabinvich emphasized that her programme with the village women in Chembe worked at its best when the women themselves were consulted. She held meetings with the local women and it was their own proposal that was finally adopted: they chose to not simply receive but to work for the limited food that Chembe Aids Project could provide. In return for porridge, they repaired roads, made a school building, cleaned the graveyard. It gave them a stake in the project and dignity.

The International Non-Governmental Organisations Accountability Charter is a major step forward in this direction. It includes a pledge to consult with beneficiaries among a number of other self-regulatory and ethical principles. Eleven leading aid agencies have committed to it, including ActionAid International, Amnesty International, CIVICUS World Alliance for Citizen Participation, Consumers International, Greenpeace International, Oxfam International and International Save the Children Alliance. Others, such as Medecins Sans Frontières, have long been following this philosophy. The Charter’s vision of accountability is inclusive and involves all the stakeholders: donors, beneficiaries, the NGO itself, partner organizations and governments and “ecosystems, which cannot speak for or defend themselves.” INGO Accountability Charter.

Meaningful networks

For NGOs to evolve towards a model of genuine reciprocity, however, the challenge now is to incorporate this democracy into the structure of the organizations themselves: making them into meaningful networks. Irit Rabinvich and Janet Townsend’s experiences show that another model is possible: a genuine network that actively involves all the people concerned. As a paradigm it is strikingly mirrored in the changing reality of the Internet. Web 2.0 was coined by O’Reilly Media in 2003 to refer to the new generation in the Internet.

|

In contrast to Web 1.0’s model which focussed on the capacity of the new technology to impose rigid marketing strategies on customers, O’Reilly’s Web 2.0 meme map shows very different characteristics. The new model is more about the people than the technology. A radical decentralization treats users as contributors and co-developers. As Wikipedia exemplifies, it means trusting your users. The architecture of participation allows for a harnessing of collective intelligence. It is flexible to user-behaviour, emergent, growing organically. If Web 1.0 gave us downloading, Web 2.0 invites us also to upload and hyperlink. It challenges us to think differently.

|

In the interest of symmetry, perhaps international donors should pay for Africans to organize workshops, outreach and other activities to teach those of us in the US and Europe how to consume less.

David Brown, USA

BBC debate: NGOs: achievers or deceivers?

It challenges the underlying assumption of western superiority. Its attitude asks what we can learn from and receive from beneficiaries culturally. It is about finding out what people want instead of deciding what they need. By understanding and moulding itself to local conditions and involving local people, asking for their responsible participation, an NGO not only respects and empowers the beneficiaries, it is developing a more effective and sustainable model. In this way, increased professionalism, accountability at both donor and beneficiary levels, and information-sharing in cooperative networks can all contribute to improving the performance and safeguarding the reputation of maligned NGOs.

Blogswana, an AIDS-related project in Botswana, sums up the new model nicely. After the traditional NGO --- “cash-intensive, centralized, hierarchical, bureaucratic, specialist-driven” --- comes a model that “bypasses the hierarchy of both the traditional charitable organization and of the recipient government. Its organization is largely horizontal. It distributes funds to a network, populated by the actual individual recipients of that aid, to do its work. It aggregates the work product of those individuals. It enlists those recipients to create and distribute the next generation of aid themselves. It’s a user-generated, entrepreneurial, person-to-person network of aid.

It’s NGO 2.0”

First published in www.myriades1.com January 2008