Lebanon and England / The non-combatants

War is a conflagration in the hearts and minds of once peaceable individuals. If the bullets and bombs are bloody and destructive, the flames of war that drive out reasoning and compassion from human souls do a damage that is no less forgivable, forgettable or injurious. When people find themselves parsed into opposing camps and conflict makes enemies of them, words in the mouths of the demagogues on either side can take on the weight and resolution of an inflexible finality: one that brooks no argument and spells out an unwanted and apparently ineluctable fate to a frightened and largely bewildered populace.

Huda Barakat lived through a civil war and the book she wrote afterwards was her response to its inescapable terror and confusion.

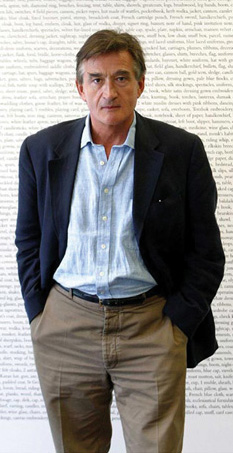

Antony Beevor is also an authority on war. As a historian, he analyzes the causes and conditions that make for war, contributing to a canon of knowledge that would teach the wise to preempt precipitation into runaway conflict, dousing the match while the gunpowder trail is still being laid.

War forces people to take sides. When a neighbouring country —now, suddenly, an enemy country— is the adversary, the choice is more clear cut. When a war sets people of the same country against each other, for political reasons, as in the 1930s Spain that is the subject of Antony Beevor’s most recent study, where brother was turned against brother, father against son, or for complex nationalist/religious/territorial reasons, as in Huda Barakat’s 1970s Lebanon, the division seems even more arbitrary and perplexing, common humanity being disallowed as an argument. And yet: “All wars are fratricidal wars,” said Barakat.

In 1975, to her eternal dismay, Lebanese-born Huda Barakat found her country divided and at war with itself --- and herself under physical and psychological bombardment, caught up in a conflict that she wanted no part of. In a Beirut split into hostile camps, words sundered also. Words became traps, death warrants. When you were stopped in the street, the inevitable questions were: Who are you? Who is your family? Are you Christian or Moslem? What are you doing here? Which Party are you with? The wrong answer could seal your fate.

“The question of who I am,” Huda realized, “defines who my enemy is and why, for reasons of race, skin colour, way of thinking…” And if she refused to take sides, refused to add another combatant to the fighting, add more wood to the fire that was consuming her people? If she decided simply, I am Lebanese, Huda wondered: what does that make me? The answer in a world where war was the lowest common denominator, denying people the complexity that makes them human, was that she was nobody. The city she lived in was being devastated by rockets and mortars, and the identities of its people were collateral casualties; when the heart of the city was ultimately destroyed and abandoned, forgotten even by the conflict, occupied only by wild dogs, “the emptiness distressed me terribly,” Huda said. A non-combatant in a non-city, she was someone who no longer counted. In Stone of Laughter, the book she wrote when the war ended in 1990 and which takes place in a thinly veiled Beirut, she would give a voice to the many other people which war robbed of their social value and sense of personal worth: “I wanted to tell the story of those lives which were lost, of people who had humdrum existences and just wanted to live normal lives.”

Huda Barakat describes, Khalil, the young protagonist of Stone of Laughter, as, “a person who has no use, who no longer functions. The character finds himself,” she said, “in the centre of the city by accident, in that no man’s land.” Her character is confronted by a shocking nothingness both within and without himself. Like his non-aligned creator, he suffers from the alienation of being an un-person, undefined, an exile in his own country, although the conflict will eventually suck him in along with his soul. Before that happens, wandering around the ruins one day, exploring the basement of a wrecked haberdasher’s, Khalil finds to his amazement that all the gorgeous coloured fabrics have survived intact. He unearths a link to memory, bearing witness to a reality where he once belonged.

From a standpoint of a survivor, Barakat writes after the war to reclaim with words what words and bombs took away. To restore value to ordinary people’s lives and to commemorate the world they lost. “In the novel,” she said, “I gave back the names to streets that no longer existed: for the beauty of remembering their names.”

Like survivors, historians are condemned to sift the past, searching for clues and patterns to a reality that they helpless to change. They are a curious breed of non-combatant, would-be intercessors in a past that is dead and gone, or a future that habitually deaf to them. Huda Barakat asserted that, “If you are a politician, you think you can change things; if you are a writer, you know you can’t.”

Antony Beevor, taking as his subject the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39, observed that emotion is stronger than intelligence once the brushwood of human conflict catches light; and then divisiveness opens the way to cruelty: “Intellectual honesty is the first victim of moral indignation,” he said.

The tragedy which was the Civil War in Spain was another inferno in the hearts and minds of fellow countrymen and citizens, whose embers are still felt in the politics of the 21st Century. The blaze that separated the different sides was initially fanned by a war of words and later stoked by propaganda of segregation and hate.

Speaking of the build-up to war in 1936, Antony Beevor said: “There are people who say that words do not kill. Yet here is no doubt that the inflammatory language on both sides increased the tension between them.” When condemnatory phrases became fixed as dogma, verbal and psychological trenches were dug on either extreme of a political divide that spurned dialogue. “Brothers and neighbours were turned into enemies by political hatred,” Beevor recounted. The flames grew to become a fire that consumed anything in its path that would dampen down its hotheadedness, anything that spoke of reasonableness, compromise, negotiated peace. It achieved such a runaway momentum and fierceness that, he said, “It is difficult to imagine that the Civil War might not have taken place.”

The manufactured chaos of war unleashes the latent fear and madness in men’s beings and makes them prey for strong and manipulative minds that offer the stability of certainty. People fled to the political doctrines of this side and that, Nationalist and Republican, in search of security and identity. The worst of the cynicism that the war of words produced was reserved for the self-immolation of the disunited army ranged against Franco. Purportedly fighting side by side with Republicans, anarchists and other elements of the anti-fascist left, the Communists —who formed by far the largest and best-organized group— used the smokescreen of the war to advance a private political agenda that for them took precedence over the winning the campaign. “Stalinist paranoia was imported into Spain,” explained Beevor, the Communists accusing non-Communist leftists of being Trotskyist fascists and infiltrators. The men of the International Brigades, for example, volunteer fighters from 52 countries who had come to support the Republic out of solidarity, were astonished at the hatred of the Communists towards them. “Every error was put down to intentional sabotage.” If lies are always perverse, this policy of coordinated fabrication was venomous. The verbal in-fighting was matched by betrayals, executions, slaughter.

Barakat and Beevor were honest enough not to pretend to offer solutions that might pre-empt future conflict. Both the author and the historian were well aware that their own words are little more than laments of voices crying in the wilderness. “Literature sometimes comes out of you as a protest,” Barakat said. “As a writer you realize how useless we can be.”

It takes much more than words. One man who has been learning about this was the star turn at the Festival, the Senegalese musician Baaba Maal, who concludes this series on word power. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Huda Barakat was born in Lebanon and today lives in Paris. She writes pieces for journalism in French and her novels in Arabic. Critics praise her High Arabic —with a Lebanese touch— which lends her descriptions such vivid realism. Barakat received the most prestigious award for literature written in Arabic, the Naguib Mahfuz Medal for Literature, for The Tiller of Waters in 2000. Her books have been published in over ten languages.

Englishman Antony Beevor was a regular officer with the 11th Hussars until he left the Army to write. He has published four novels, and eight works of historical non-fiction. Stalingrad, first published in 1998, won the first Samuel Johnson Prize, the Wolfson Prize for History and the Hawthornden Prize for Literature in 1999. His latest book is The Battle for Spain, a completely new edition of his 1982 book on the Spanish Civil War, which was a Number 1 Bestseller in Spain.

Next article Back to introduction